E3: The future of fear in video games

- Published

- comments

Alien territory: Preparing for E3

Video games are getting scarier - much scarier. Is a line about to be crossed?

A Washington Post review of the classic horror flick The Blair Witch Project painted it as being so scary, and so unsettling, that it was a "stomach-quivering, skin-crawling, bathroom-dashing" experience.

People were literally running out of cinemas, the newspaper reported. Often to be sick.

Box office sales instantly went through the roof.

At E3, held in Los Angeles this week, the biggest games companies in the world are gathered. A big theme this year is the desperate desire to produce the gaming industry's Blair Witch moment.

Easy tricks

We've been close in the past.

Early on, the Resident Evil series broke boundaries for what could be considered a scary gaming experience. Later, Silent Hill brought in a psychological fear.

But for the most part, horror games have mostly been about making people jump - which is a relatively easy feat.

The protagonist in Dying Light is pursued by predators that appear after sundown

"I think we're kind of fed up with all the easy tricks," says Tymon Smektala, a producer from Techland, the Polish developer behind Dying Light, a big-budget survival horror game.

"Monsters in the closet... that's been done before and everyone knows they should expect a monster in the closet when they approach one."

Dying Light is a first-person game in which the player has to survive in a 28 Days Later-like scenario - infected zombies everywhere, desperate for a nosh on your flesh.

Where its title differs from other zombie gore-fests, the studio says, is the introduction of a day/night cycle.

As nightfall approaches, the gamer will become anxious, even if they're not being attacked right at that moment, due to the impending danger that night-time can bring.

Unimaginable terror

Like many other developers at E3, the Techland team is experimenting with virtual reality.

Developers are using the new consoles to show gore in more detail than before at E3

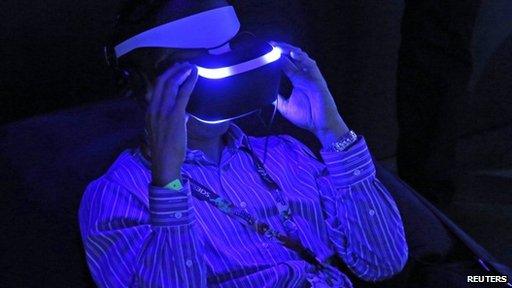

Both the Oculus Rift - now owned by Facebook - and Sony's Project Morpheus have a sizable presence at the event. The technology is a game-changer, particularly in scaring the life out of people.

"The things you could do are almost unimaginable," says Dave Ranyard, head of Sony's London studios, the hub of the firm's work in VR.

He believes that virtual reality can bring horror to a level that surpasses even the most terrifying films.

"If you're watching a movie, you're experiencing it second-hand. Fundamentally, the reason you can enjoy it is empathy. The great scriptwriters mean you fall in love with the characters and you don't want them to get hurt.

Sony's Project Morpheus headset helps players become more immersed in games

"In VR, it's actually you. It's a really interesting philosophical point: It's. Actually. You."

Get me out of here

Project Morpheus is not available to buy yet, and Oculus Rift is only purchasable as a prototype. Most predict a 2015 or later launch for both.

But those who have managed to get their hand on early beta versions of Oculus Rift report mixed results.

The Washington Post's description of the Blair Witch Project holds strong: for many, virtual reality horror is a "stomach-quivering, skin-crawling, bathroom-dashing" experience.

Alien: Isolation challenges the gamer to survive being hunted on a space station

Videos have surfaced of gamers playing suspenseful horror games on the Oculus, but quickly pulling the headset away from their head when it all gets a bit too much.

"You can really feel it in your guts," says Maciej Binkowski, lead game designer of Dying Light.

"You really face the monsters in front of your nose.

"I hope nobody will end up with a heart attack."

He's joking, of course. But only just.

Meanwhile, Alien: Isolation - a sequel to Ridley Scott's 1979 movie - has been described as being 10,000 times scarier, external on the Oculus Rift than the already petrifying experience of playing it in front of a TV.

Crossing the line

With its combination of highly-realistic visuals, surround sound - "he's behind you!" - and an interaction obviously not possible with film, there's a developing consideration that gaming could produce genuine moments of terror we are just not used to in an entertainment setting.

The Evil Within is a new game from Shinji Mikami, who previously created Resident Evil

"I'm sure there probably is a line," says Pete Hines, responsible for PR and marketing at Bethesda, another developer with a big-budget horror title - The Evil Within. In this game, another zombie fest, it's often wise to avoid conflict.

"It's the absence of anything going on sometimes that can be really unsettling," Mr Hines says.

"There has to be moments of intense panic and horror, and then moments where nothing is happening - it gives you a bit of a break.

"It's about finding the right balance of those kind of things."

Mental battle

It could be argued that the scariest thing about the big-name horror titles at E3 is the money spent on creating them.

Indeed, if the games industry wants to truly find its Blair Witch, it needs to seek inspiration from the film's own beginnings.

An independent production, on a budget of around $35,000 (£20,890), it was far from being a big blockbuster.

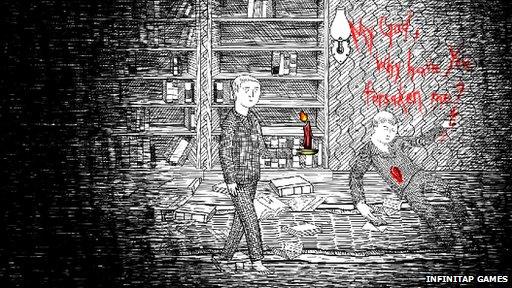

Neverending Nightmares is based on its developer's battle with mental illness

Which is why perhaps Matt Gilgenbach, an independent developer in a small corner of E3, might be closer to the mark.

His game, Neverending Nightmares, is genuinely disturbing.

"I've had a lot of violent thoughts of self-injury that have tormented me for years," he says.

"So through the premise of a horror game I'm able to share those with other people."

Mr Gilgenbach plans to release Neverending Nightmares for Mac, Linux, Windows and Ouya systems

After his first game failed, Mr Gilgenbach turned to crowdfunding site Kickstarter - raising just over $100,000 for his horror title. It's a simple but artistic game that has a distinctive pen-drawing graphical style.

Mr Gilgenbach says it's a chance to express his own battles with mental illness.

"If you look at the very graphic bone violence, that's actually an intrusive thought I've struggled with - a side effect from obsessive compulsive disorder."

Neverending Nightmares is not in full, glorious, textured 3D. Nor is it virtual reality compatible.

But those who come away from playing it are left deeply unsettled by powerful, innovative story-telling.

It's a glimpse into a world far scarier than zombies or aliens.

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external.

- Published11 June 2014

- Published11 June 2014

- Published10 June 2014

- Published10 June 2014