Why Germany won't fight deflation

- Published

- comments

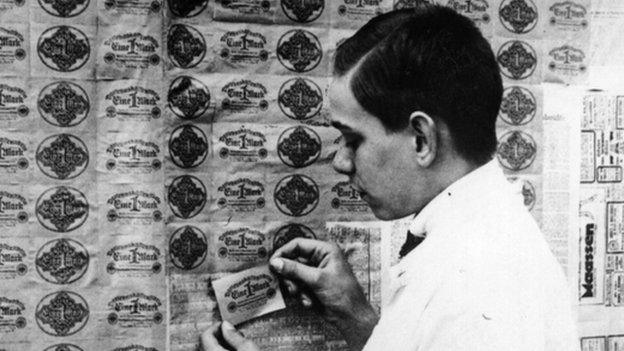

Rather than buying wallpaper in 1920s Germany, it was cheaper to use banknotes

The risk of intractable, growth-destroying deflation in the eurozone has intensified. Will Germany block attempts by the European Central Bank to buy government bonds to ward it off?

Nothing desperately fundamental has changed in the global economy in the past few weeks.

As I bored on about this morning, it has been clear for months that the eurozone faced a risk of prolonged stagnation, that China's growth could slow very sharply and that emerging economies in general may be past their peak of expansion.

But all of a sudden investors are worrying that the global recovery that took years to take hold after the 2008 crash is already running out of puff.

Today's news reinforcing the gloom was that prices are falling year-on-year in eight EU countries and are dropping month on month in 11 EU countries.

That looks quite a lot like deflation.

And a little bit of inflation is much healthier than a bit of deflation.

If businesses and consumers come to believe that prices are on a downward trend, they delay investment and spending - to take advantage of lower prices.

Which sucks the economy into a contractionary spiral - thus reinforcing the deflation.

And there is something else that is spooking investors, namely that Germany may succeed in blocking the European Central Bank from buying government bonds (or engaging in the kind of quantitative easing we've seen in the US and UK) to force down the cost of finance in the eurozone and thus stimulate the economy and inflation.

Germany's concerns are viewed by some as anachronistic: it worries that creating new money in this way will eventually annihilate the credibility of the euro and spark hyperinflation (of the kind that destroyed the German economy and democracy in the 1920s).

But inflation seems a remote risk right now.

Even so, the head of Germany's central bank, the Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann stresses that the ECB is banned from lending to eurozone governments, i.e. from financing them.

So the question is whether that prohibits buying government bonds in the secondary market (or from investors, rather than directly from governments).

The president of the ECB, Mario Draghi, says it does not.

But the sharp falls in the prices of Greek, Spanish and Italian bonds today implies that investors see potential ECB buying as reinforcing the ability of the Greek, Spanish and Italian governments to borrow.

So in that sense secondary market purchases would indeed be a way of financing those governments.

In other words, the reaction of investors may reinforce German fears - and make it even less likely that the ECB can take the kind of evasive action deemed necessary to ward off intractable deflation.