The fear of censorship in Indian media

- Published

Mr Modi prefers to interact with people through social media and radio talks

George Bernard Shaw once said that "censorships exist to prevent anyone from challenging current conceptions and existing institutions".

A recent outcry in India shows just how many fear this in Narendra Modi's government after it accused three TV news networks of violating broadcasting regulations , externalby airing interviews that criticised last month's execution of Yakub Memon, the man convicted of financing the deadly 1993 Mumbai bombings. It even threatened to cancel the licenses of the channels for violating broadcasting laws.

Memon's execution was controversial - there were reports that he had been betrayed by Indian authorities, external after being coaxed into surrendering. He had also spent two decades in prison as legal proceedings dragged on. His execution triggered a debate on the death penalty and "selective justice" in India. His mercy pleas were rejected twice by the president and appeals to suspend the execution were discarded by the Supreme Court, the last time in an unusual early morning hearing., external

But in what many journalists see as a crude form of censorship, a terse directive was issued by the Information and Broadcasting Ministry, external, which has Orwellian echoes in a country that prides itself as the world's largest democracy. It argued the broadcast interviews contained content which "cast aspersions against the integrity of the president and judiciary".

So what offended?

In one of the interviews, a former lawyer of Memon was quoted as saying that one man charged over the blasts had been pardoned by the courts despite playing a bigger role in the bombings than Memon himself. "If you show this pardon to any person outside India - UK authorities or US authorities or the best brains in the world as far as criminal law is concerned - they will laugh at you," the lawyer said. "They will laugh at you. They'll say, "Is this justice"?

Another apparently disrespectful interview was with a Mumbai underworld figure who is at large and described as one of the masterminds of the bombings. Chhotta Shakeel called up the channel to claim that Memon's execution was "legal murder", external.

Yakub Memon's execution triggered a debate on death penalty in India

The networks lost no time in taking umbrage at the directive, saying that the government's reasoning was "questionable, external" and that they had followed ample self-regulation in covering terror-related incidents.

India's cable network laws already limit media coverage of anti-terror operations to "periodic briefings" by government press officers until the operation ends. Top lawyer Indira Jaisingh says the government "cannot fight surrogate battles", external on behalf of the President and the Supreme Court. "Long years ago, the Supreme Court said the air waves belong to us all, and that free speech cannot be curtailed by the denial of a licence to broadcast - something the government is trying to do," she wrote in Indian news website The Wire.

'March of the democratators?'

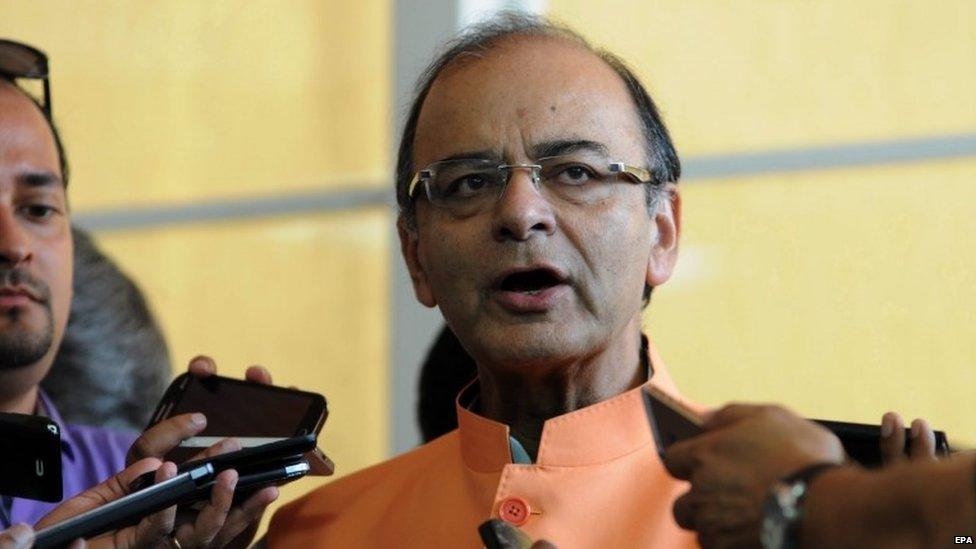

One of the great ironies here is that the broadcasting ministry is run by Arun Jaitley - also the finance minister - who is seen as a moderate face of the government and who, according to a senior journalist, "believes in live and let live".

As an opposition student leader in the 1970's Mr Jaitley spent 19 months in prison when Indira Gandhi suspended civil liberties during the infamous Emergency and imposed the harshest clampdown on media in the history of Independent India. "Media censorship is not possible today because of technology," Mr Jaitley told a gathering at a launch of a book on Emergency in June.

So why is Mr Modi's government issuing such fiats?

Part of the problem, say many, may have to do with Mr Modi himself - he prefers the formality of clipped and controlled social media messaging and radio dialogues to the informality of open and frank media interviews. In some ways, say his critics, he conforms to a pattern set by leaders such as Vladimir Putin or Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who, according to Joel Simon, author of The New Censorship: Inside the Global Battle for Media Freedom, use their massive mandates to govern as dictators or "democratators".

But it is also the case that Mr Modi has long preferred to interact with the public directly, unmediated by journalists, and it is a strategy that has served him well, winning him the adulation of many young Indians who identify with such direct contact.

Mr Modi's office is also seen as one of the most centralised in recent history. "That is where things are going wrong," says journalist Neerja Chowdhury. "You can't run a country like India if you centralise power."

Arun Jaitley, who heads the information ministry, is a seen as a moderate force

Senior journalist Shekhar Gupta writes that the "first indication that a government is losing nerve, external or grip when it starts blaming and targeting the media".

It is absurd, he says, for the government to believe it can control the media today's pell-mell world of social media. "A war on the news media causes any government terrible, often terminal damage. It does no real harm to the media," he writes.

India, already, needs more press freedom than many of its democratic counterparts. This year, it ranked a lowly 136 out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index, external. Its ostensibly thriving media can often be an an illusion.

But the biggest mystery is why a government with one of the most comfortable majorities in Independent India feels the need to flex its muscles this way. Could it be an early sign of insecurity?