Inside the home of Indonesia's most notorious IS militant

- Published

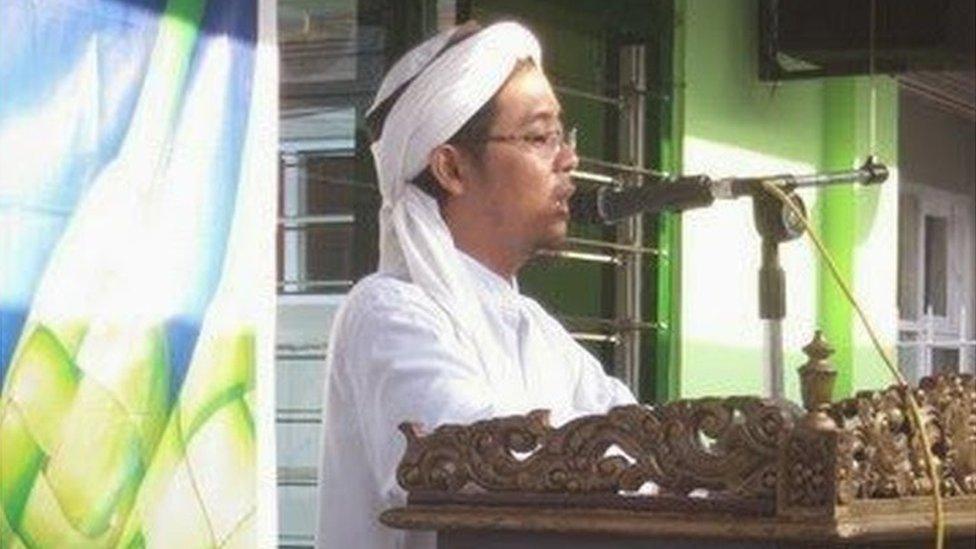

Bahrun Naim, 32, the alleged mastermind of the Jakarta attacks, is from the small town of Solo

After a small but determined terror cell brought scenes from a war zone to central Jakarta, the BBC's Karishma Vaswani travelled to the town of Solo to find the family of the alleged ringleader, Indonesia's most notorious member of the group which calls itself Islamic State.

Bahrun Naim is accused of co-ordinating the attack from Syria.

It was an ordinary Thursday morning in Jakarta and little did commuters know, as motorcycle taxis ground through interminable traffic, that young men with guns and murder on their mind would soon be among them.

At 10:43 a small group, laden with explosives, suicide vests and firearms, walked into a Starbucks cafe and unleashed the worst. Five hours later they were all dead. The so-called Islamic State said they carried out this attack, its first in South East Asia.

The attack brought chaotic scenes to the streets of central Jakarta

If the killers planned mass slaughter, they did not succeed. Four civilians were left dead. But it is their ambition that is worrying.

They appeared untrained but had the worst of intentions. The attack came amid vague warnings but more significantly after a spate of pledges of allegiances to IS across the Indonesian archipelago by small groups of young men and women.

The answer to why these young Indonesians are becoming more radicalised lies in places like Solo, 400 miles (650km) away.

Many believe that Indonesia's new young breed of radicals were cultivated in this city, including the country's most notorious son, 32-year-old Bahrun Naim.

Authorities say he went to Syria in 2014 to fight with IS and is believed to have planned and funded these attacks.

Roots of radical ideology

Solo - or Surakarta - is a small and sleepy town, criss-crossed with paddy fields.

About half a million people live here, and amongst its claims to fame is that President Joko Widodo is from here.

Karishma Vaswani speaks to the brother of Bahrun Naim, who authorities believe planned and funded the recent terror attacks in Jakarta

But officials say several militant groups have also emerged from here. Abu Bakar Bashir, the alleged spiritual head of Jemaah Islamiah - the group responsible for the Bali bombings of 2002 - set up a school here, one that many academics say still spreads radical ideology.

Naim also studied in Solo - not in Bashir's school, but in one not far away - and it's thought this is where the roots of his radical ideology first began, as did his journey from internet cafe operator and mathematics student to militant in Syria.

The house of Bahrun Naim where the family were not keen to talk to journalists

'We aren't terrorists'

Solo has struggled in recent years to be as economically successful as cities around. It used to be a textile manufacturing centre but has lost out to other more competitive production hubs.

Experts say the economic malaise is one factor pushing young men to the call for jihad.

With newspapers screaming out headlines about the shocking assault - "ISIS mastermind a Solo boy" - a vendor selling papers in the local park said simply he felt "ashamed".

"Very, very ashamed. I don't know whether it's true or not but the people of Solo aren't like this. We aren't terrorists."

It is also the talk of the local market, which is where I met Yati, a neighbour of the Naim family.

Yati claims there is a growing number of young radical Muslims in the area

"They keep to themselves," she tells me. "They are very private, very quiet. They never mingle with the rest of us."

She also tells me about the increased number of young radical Muslims in the area, who often, according to her at least, launch raids on late night singing and dancing events, breaking up parties and celebrations.

"We've learned to hold our events earlier on in the evening," she says. "Otherwise we could risk them coming and accusing us of drinking alcohol. That would cause a lot of trouble."

'Not guilty'

I tracked down Bahrun Naim's family to a blue and white painted house on a small side street. It is boarded up and looks deserted and it is clear the family are not in a welcoming mood.

"We aren't talking to any journalists!" says Naim's father. Eventually he agrees to let us in.

It is a simple, plain house. In the corner, a makeshift kitchen where the family cooks food to sell. Their small convenience store appears to have been shut down too, although they tell me that they will still sell to those who are familiar to them.

Naim's mother is a quietly fierce lady, her anger at the media etched on her face. She and Naim's father refuse to speak to me - only his younger brother Dahlan agrees, albeit reluctantly.

Naim's brother and lawyer say there is no evidence he is guilty

"Bahrun went to Syria to study, and he is not involved in this," he told me. "My friends keep asking me what's going on. My university teachers say I come from a family of terrorists. But the police have only pointed a finger at my brother, and it's not even clear if he's guilty."

Naim's father filmed the conversation and wanted to know where I was from and where I lived. Their suspicion of outsiders was unsettling, but perhaps understandable given the scrutiny they are under not just from the locals, but also authorities.

At least four policemen on motorcycles passed by the house. Some neighbours told me intelligence officers had been spotted in the village.

'Radicalised in prison'

Naim's former lawyer Anis Priyo Anshori, appointed by the family, says he has been made into a scapegoat.

"He was a quiet, creative man," Mr Anis told me. "He is very intelligent but kept himself to himself."

He admits Naim had a previous brush with the law. In 2010 he was convicted of possessing ammunition, a case that saw him go to prison for two-and-a-half years.

"He has been in jail, and that, too, for a crime that I don't believe he committed. Now they are doing it again," Mr Anshori insists. "As far as I know when he was younger he had joined a radical group, but it wasn't one with a violent track record. Just because he was part of this group, doesn't mean he carried out the attack."

Naim's former lawyer describes him as quiet, creative and intelligent

Most experts believe he was radicalised, and it was his school or prison that radicalised him.

Police say militants regularly frequented the mosque that Naim's school was run by, although the school's directors have reportedly said they only teach the Indonesian curriculum and are not a hotbed for extremist ideology.

But it does point to a larger problem that Indonesia is facing - policing what goes on in some of its schools and more importantly prisons. There have been allegations that Abu Bakar Bashir for instance is still able to hold weekly lectures behind bars, spreading his radical ideas to a readily available group of recruits.

Intelligence authorities also believe Naim was one of those initial recruits, although so far there is no evidence to prove that there's a direct link between Bashir and Naim, even though they are both from Solo.

Ever since relocating to Syria, authorities say Naim has been instrumental in recruiting and planning attacks against Indonesia. In a blog attributed to him, Naim praises the Paris attacks and urges his followers to do the same in Indonesia.

'Super hero' brand of Jihad

Indonesia itself is the world's most populous Muslim nation - for the most part moderate and run by a secular government. It has been fighting extremism for decades.

But in the last few years, ever since the so-called Islamic State has started recruiting in earnest, it's thought that 500 - 600 Indonesians have gone to Syria to fight. There are also thought to be 1,000 IS sympathisers on the ground.

That's not a lot in a country this size, but authorities are concerned because of the nature of the appeal. They say young Indonesian Muslims are particularly taken with the "superhero" brand of jihad IS is selling.

A history of militancy in Indonesia

"Studying Islam, it's not cool, it's not heroic," says Taufik Andrie, a researcher in militant extremism. "But jihad - it is cool. And it has a sense of adventure about it. That's what these young men are after.

"There are 21 groups affiliated with militancy in Indonesia; seven of them support IS, and amongst them three groups are very focused on recruiting fighters for Syria," say Hamidin, spokesperson for Indonesia's anti-terror agency.

"These are the young guns, terrorists aged between 18 to 30. They may not have the capability to assemble bombs, but they just want to look like they're doing something and show off. They want to look like they're in the thick of the action."

That was what we saw last week and this mixture of hubris and misplaced ideology has become a lethal combination, one that has led authorities to believe this isn't the last attack we'll see on Indonesian soil by followers of IS.

- Published14 January 2016

- Published14 January 2016

- Published14 January 2016

- Published17 January 2016