Japan's retirees: industrial waste or a silver lining?

- Published

Japan's ageing population offers a silver lining

Working after retirement is not something many plan for, especially in Japan, where most white collar workers - known as salarymen - still devote their lives to one employer for an average of four decades.

The feeling is, once you reach 65, retirement offers a well-deserved break. But that doesn't suit everyone.

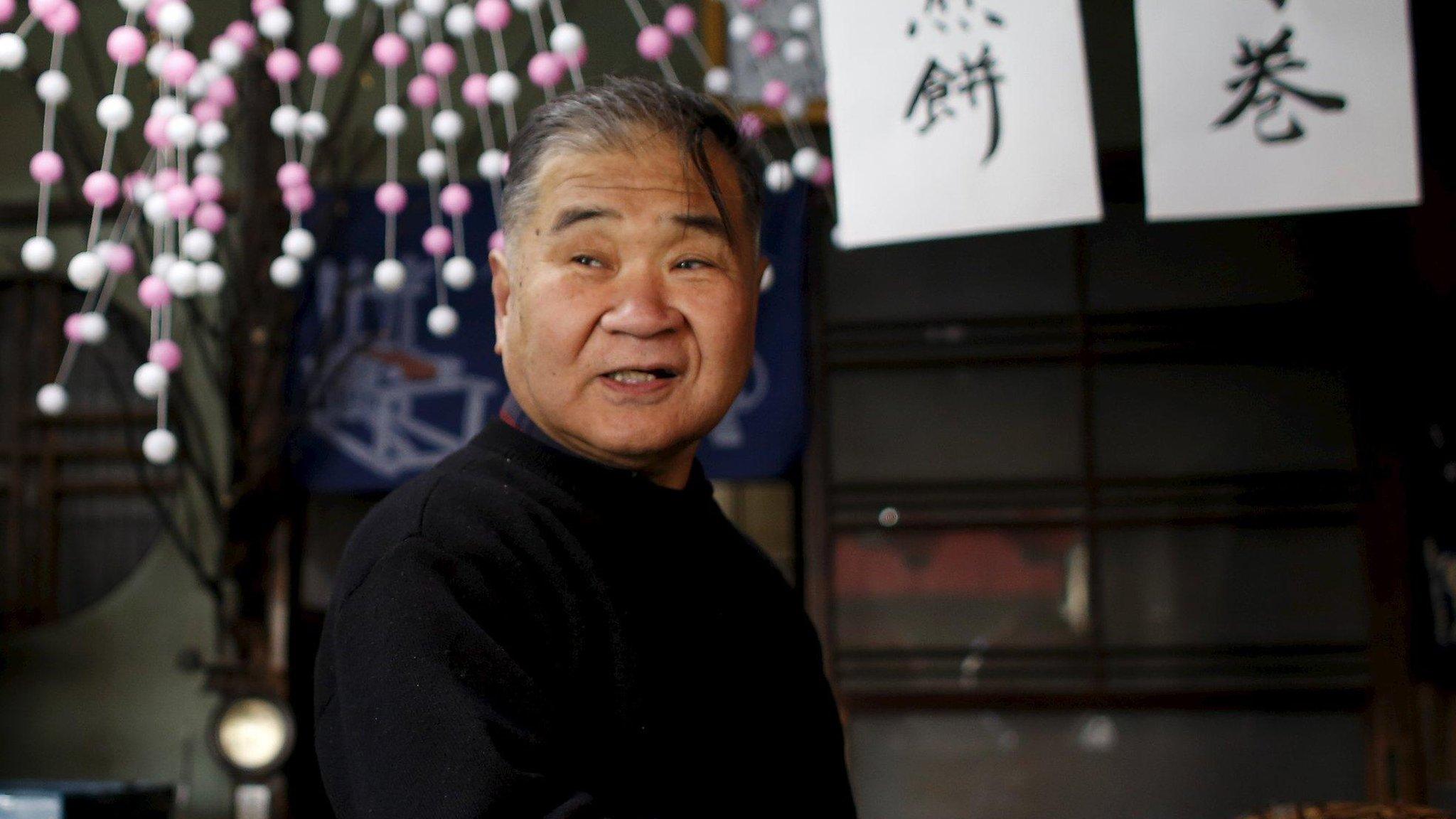

When 67-year-old Akio Kouyama was asked by a former colleague to join his human resources company, he was very keen.

"The first year after retirement was fun. You travel and enjoy your hobby but after that, you start to wonder if it is ok not to use your skills in the workforce," he says.

The human resources company that he joined is exclusively for retirees who are eager to work.

It has over 750 registered members whose average age is 69 with the oldest being 81 years old. They can choose from over 30 assignments such as being receptionists or personal drivers.

Silver talent

The company is called Koreisha which translates to "the elderly" in Japanese.

"Our founder was told that the solution to Japan's shrinking working population lies in elderly, women, foreigners or robots. So he started a firm which can help Japan utilise its silver talent," says Mr Kouyama who has since taken over the top job at Koreisha.

Koreisha finds works placement for its members, all of whom are retirees

Japan's workforce is shrinking fast.

When Koreisha was founded in 2000, the proportion of Japan's population above the retirement age, external was 17.4%.

In February 2016, external, that statistic has jumped to 26.9% and is expected to rise to 36.1% by 2040.

Spending on healthcare and pensions already accounts for one-third of the country's annual budget and it is ballooning fast.

Koreisha's founder, the septuagenarian, Kenji Ueda, has cheekily referred to retirees as "industrial waste" who should be recycled, rather than getting under their wives' feet at home.

"At our age, we don't want to work full time, so most of our members only work two to three days a week," says Mr Kouyama.

Mr Takano works part time as a gardener in central Tokyo

For 68-year-old Rikizo Takano, his office for twice a week is a rooftop garden in central Tokyo with a magnificent view which includes the Tokyo Tower and the rainbow bridge. At first sight, his job of tending to a client's garden looks almost like a hobby.

"Before retirement, I used to work on factory constructions so I am a certified landscape engineer. I know what kind of soil should be used for a rooftop garden and it is nice to be able to use my skills again," he said.

Mr Takano and other Koreisha members don't get paid a lot of money. On average they receive an hourly income of 800 (£5; $7) to 1,000 Japanese yen which is roughly what students earn by working at a restaurant.

Pocket money

But low pay is not necessarily a problem.

"As long as you don't work over 30 hours a week, or earn more than 400,000 yen (£2,497; $3,528) a month, it doesn't affect pensions," says Koreisha's Mr Kouyama.

"It is great pocket money that they can use to spoil their grandchildren," he adds.

"At our age, we don't want to work full time" Akio Youkama, Chief Executive Officer at Koreisha

But Japan is traditionally a Confucian society and the norm would be for older workers to earn not only more money but also more respect in the workplace. That has been a challenge for some of those returning to work in more junior roles.

"We educate ourselves that if we want to rejoin the workforce, we have to do so as newly hired employees. We need to be humble. Young people may learn from us by watching how hard we work, but not because we stand on our dignity," says Mr Kouyama.

Hierarchy, however, is deeply entrenched in the Japanese society.

Crossing over

So when 75-year-old Masatoshi Tsuneno created a group to help the local community in Kashiwa city, he made it a rule among the group, that they would never mention or discuss their previous occupation and job titles. The group has over 100 members, and they call themselves 'a community of multi-generation interaction'.

When I asked him what he used to do - even off the record - he still wouldn't say, adding that it is important for his peers to be able to treat each other equally, even if someone was formerly a chief executive or diplomat.

What Mr Tsuneno's group does in Kashiwa is not high-powered.

In Kashiwa City, a group of elderly operate the school library at extended hours so students can study before or after their lessons

They supervise school crossings for example - lollipop men or ladies as they're known in the UK - to make sure the children in the neighbourhood get to school safely. They open the library outside school hours to help children study before and after classes. They also volunteer their time at a day-care facility, and the female members would visit new mothers, to check in and make sure they are settling in well with their newborns at home.

Morning greetings

They can be considered as 'stand-ins' for parents, or grandparents even. That's because for many of the residents in Kashiwa, their own extended family do not live in the same neighbourhood. And this interaction between the generations is exactly what the government wants more communities to do, external across Japan.

The Japanese government has been urging for more interaction between the young and old

Mr Tsuneno says the positive impact can be seen through the lower crime rates, as well as the growing number of young families settling in the area.

"It's nice to hear some children who were very shy several years ago greet us properly in the morning," he says, "but it's also great for us to be able to do some good for the community instead of just doing nothing at home."

Whatever his past position, however senior it may or may not have been, his new role is clearly giving him a keen pride, and a sense of being of service to his community, something he may not have got from sitting at home in his slippers.

- Published26 February 2016

- Published19 August 2015

- Published16 March 2015