Uganda: 'One of the best places to be a refugee'

- Published

Why is Uganda the best country for refugees?

Uganda has been praised for having some of the world's most welcoming policies towards refugees - the BBC's Catherine Byaruhanga has been finding out what is on offer.

The Nakivale refugee settlement, six hours' drive west of the capital, Kampala, is awe-inspiring.

It stretches for 184 sq km (71 sq miles) and covers rolling hills, fertile fields, a lake and many streams. Dotted around the landscape are small brick or mud houses, some with corrugated irons roofs.

This is home to more than 100,000 people who have been granted refugee status here, and Khadija al-Hassan, who fled the fighting in her home country of Somalia six years ago, is one of them.

The 46-year-old has built a simple home for her and her children and tends a small plot of land where she grows vegetables like carrots, aubergines and chillies.

She likes the life here: "There is no problem in Uganda. Refugees are given houses, food and free education for their children. You can even sleep in the open and no-one will bother you."

Khadija al-Hassan, Somali refugee in Uganda

"There is no problem in Uganda. Refugees are given houses, food and free education for their children."

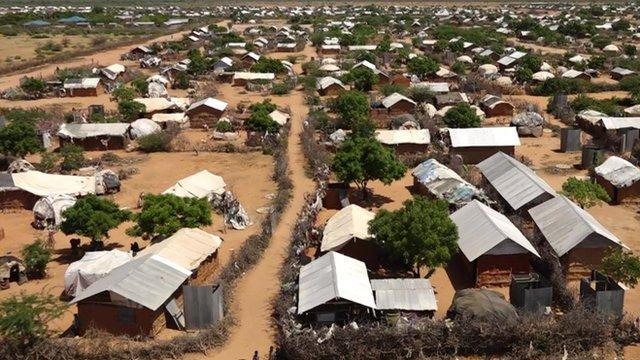

As the number of refugees continues to rise around the world, many countries are struggling to cope. This week, Kenya announced its intention to close the Dadaab refugee camp, which houses more than 300,000 refugees from Somalia.

The UN refugee agency, the UNHCR, has praised Uganda, external as "having progressive and forward-thinking... policies" for the more than half a million refugees in the country.

"The Uganda model is almost unique in allowing refugees the freedoms that they are granted," says Charlie Yaxley, UNHCR spokesperson in Uganda.

"For example in Kenya, where we have the Dadaab and Kakuma camps, refugees are restricted within those camps and not able to work.

"That is not the same here in Uganda, where refugees are given the opportunity to contribute to the local economy."

The rolling hills and fertile fields make Nakivale an idyllic place to live

One thing that makes Uganda unique is that refugees are taken in immediately and helped without a lot of questions or suspicions.

At the heart of this generosity may be that many people in power know what it is like to be forced to flee.

The decades following independence in 1962 saw several internal conflicts, which created thousands of refugees.

Even President Yoweri Museveni and some of his cabinet colleagues have been exiles themselves.

And in the last 20 years nearly all the countries that border Uganda - the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Kenya and South Sudan - have had conflicts which have sent people running here.

Refugees in Uganda are allowed to work and contribute to the local economy

As cultures and languages straddle national borders, Ugandans often share family or ethnic ties with some of the people who have come here, making integration easier.

Despite this, many refugees still dream of home.

Cedric Mugisha fled here from Burundi via Rwanda. Still visibly traumatised after having to run away from home, he wanted to make it clear that being a refugee is never anyone's first option.

"In Burundi, I have a life, my life was promising. I miss my family, I don't know where they are, and I don't know what happened to my friends."

But all is not rosy and there is some suspicion of the refugees.

At the edge of the Nakivale settlement are villages where Ugandans live. Some of them are not happy about how much help the refugees get.

Stephen Kafungo, Ugandan farmer

"I have stayed here for 30 years and I had 143 hectares. Now with all the refugees coming, all the land has been taken."

Many here are subsistence farmers and they complain that they have had their land taken away to make room for the refugees.

The government argues these are areas that had been earmarked for those seeking asylum.

But farmer Stephen Kafungo is angry.

"I have stayed here for 30 years and I had 143 hectares. Now with all the refugees coming, all the land has been taken.

"I don't know [the] future, because if I die my children will have to suffer."

And this is the challenge for Uganda's refugee policies.

It has one of the youngest and fastest growing populations in the world, making land and other resources increasingly scarce.

But for now the government and people are determined to care for those in need the best way they can.

- Published3 February 2016

- Published6 May 2015

- Published13 May 2016