Snipers and green tea on Helmand's front line

- Published

Police and Taliban positions can be just a short distance apart in parts of Lashkar Gah

When I went back to Helmand I expected to find fighting, opium fields and new frontlines. But I didn't expect it to be so hard to distinguish between warring sides. And the fall of Sangin while I was there came as a big shock, writes BBC Afghan's Auliya Atrafi.

Going home to Helmand felt different this time - things really are unstable.

The last time I witnessed such a fluid situation was in the early 1990s after Kabul had fallen to the mujahideen.

A few communist families were in control. After that Helmand was ruled by the mujahideen and then by the Taliban. For the last 15 years, however, it's mainly been ruled by the Afghan government, although it's still considered a Taliban heartland and a centre of insurgency, smuggling and opium.

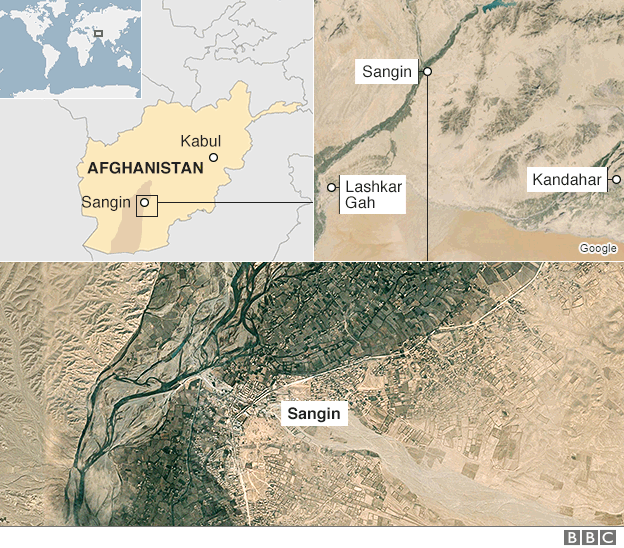

I took the road from Kabul to Helmand via Kandahar in mid-March - a precarious 10-hour bus journey. In recent months the main road leading to the provincial capital, Lashkar Gah, has been in and out of government control.

From the bus I saw police stations that had been partially blown up by the Taliban. Bridges had been destroyed. The roadside was littered with the carcasses of burnt-out government Humvees.

This is normally the scariest part of the journey, as Taliban fighters try to kidnap government personnel, but I didn't encounter any.

'Taliban cousin'

Despite being surrounded by the Taliban, people in Lashkar Gah were calm. The Taliban seemed to be on the defensive as the government had started clearance operations.

A few times a day American Apache helicopters flew overhead, a reassuring sign the Taliban wouldn't be allowed to take over the city.

The Taliban take the American planes seriously; when they briefly captured the northern city of Kunduz in 2015, they paid a heavy price.

Nonetheless, staying positive was difficult. As one trader put it: "Life is shaky and people are disappointed with governance. Fighting is so close that when we sleep at night we can hear gun shots.

"Travelling is dangerous and takes longer, and schools are barely functioning. People are generally upset."

Amid the instability, locals are trying to move forward. But they are also aware their city could move from government to Taliban hands.

Many of the pragmatic Helmandis have found a guarantor - "a Taliban cousin" - among the insurgents in case the city falls.

"The Taliban told me to live in peace; they said their friends would arrive at my place as soon as they take the city," one resident said confidently.

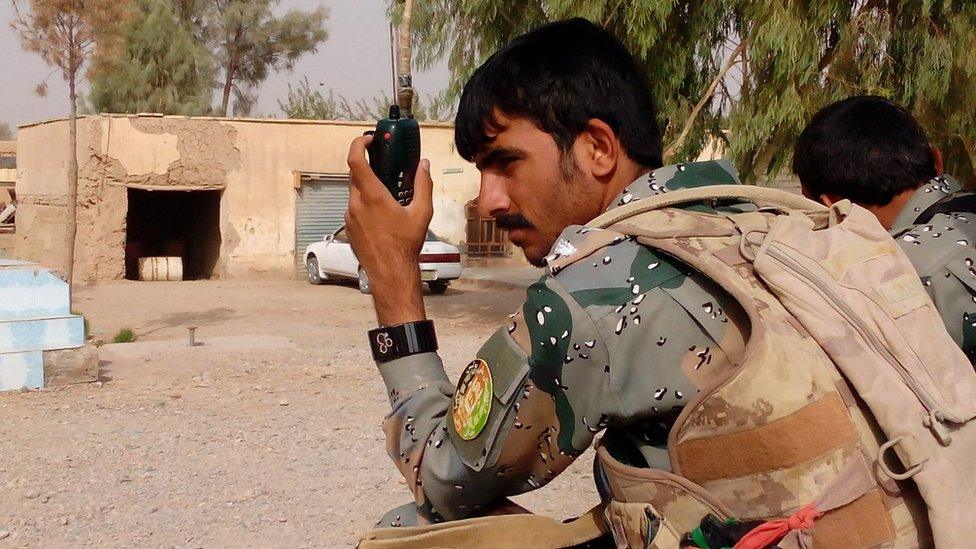

Security personnel use what cover they can to observe the Taliban

Helmand is mostly made up of Sunni Pashtuns but it is also has a large Shia community.

The Taliban do not target Shia, unlike other Islamist extremist groups who view Shia as heretics. But Shia are generally pro-government and making such alliances has proved harder for them than their Sunni neighbours.

In Gereshk, north of Lashkar Gah, Shia are caught in the crossfire between a Taliban hotbed, Nahr Seraj, and the city.

Locals are scared and some remember violence that erupted in the early 1990s when the mujahideen took over the district.

"A commander called Rais of Baghran came. He took people out of their houses and shot them; he kicked people out and looted their properties," said district committee member Mirza Khan.

"We left everything behind; families fled in the middle of the night and migrated to Pakistan and Iran… We fear that might be repeated again."

It wasn't just Shia - as the communist government collapsed, many communities experienced similar treatment. But Shia in Gereshk say they were targeted by the commander while Sunnis were left alone.

Mirza Khan also says two tribal elders who appealed to the Taliban for the release of a prisoner two years ago were killed - something he calls a "sort of bias".

Helmand is at the heart of Afghanistan's opium trade

The Taliban say they have no racial or sectarian bias: "What has happened must have been a personal issue," a Taliban spokesman told the BBC.

Fear is not restricted to the Shia. In Lashkar Gah, the front line is on the city's western edge. I went to pay a visit to the border police battalion in the Bolan area.

The front line here is a crowded neighbourhood where children still play traditional games outside. But most of the houses lie empty, used by the warring sides.

We were advised to drive faster on some corners as the Taliban shoot at vehicles.

Commander Juma Khan thought it better we had tea inside his office, saying: "The Taliban threw a grenade into our courtyard a bit earlier."

"Are they so close?" I asked with a mixture of fear and astonishment.

"Yes," said Juma Khan, adding: "They sometimes throw stones at us from the other side of the wall."

I later heard that the two sides can hear one another - they even jokingly invite each other for tea, though the offer is always rejected.

The police station had many holes for observation and snipers. Some were on the roof and some were small tunnels.

It was hard to see much through the holes, but as we drank green tea in the commander's office there was a constant exchange of small arms fire.

Security personnel man checkpoints on key roads in Lashkar Gah

The conflict in Helmand is complex; it is not about blind hatred and mindless killing. There are families who are fighting on opposite sides without feelings of hostility.

Taliban commanders claim huge influence over government institutions. Tribal alliances and economic incentives are more important than ideology.

Business transcends borders; right now there are four multi-million dollar infrastructure projects funded by the government moving forward despite the fighting.

South of the Bolan hills is the road to Nad Ali and Marja districts. A local resident told me of a traffic policeman who was seen serving at rival checkpoints.

"He would manage the traffic at the government checkpoint; when things got bad at the Taliban checkpoint, they would call him and he'd ride his rattling moped and bring order at the Taliban checkpoint."

Infighting

Still, fighting continues and the Taliban generally hold the upper hand. According to the provincial council more than 85% of the province is still under insurgent control. Of 14 districts, seven are in Taliban hands; two are under siege; in the rest, the government operates in central areas only.

Troops - like this man here clearing IEDs - have cleared the road to Nad Ali

To the west of Bolan lies Nad Ali. Security forces managed to clear the road to the centre after months of Taliban siege. The white flags of the Taliban indicate the front line, a few hundred metres from the main road.

Government casualties were not too high during the Nad Ali operation. Air support played an important role but one of the operational commanders, Bismillah Jan, believes lines are generally thin on the Taliban side.

He believes if he's given men and aerial support he can beat them back. But the security forces also lack personnel - as the decision to abandon Sangin showed.

The government strategy seems to be to gather scattered forces and unite them as a solid front in central Helmand. But as soon as fighters were freed from Taliban sieges, many disappeared.

"Our 20 or so friends in those remote bases kept 200 Taliban busy. Now the Taliban can join together and attack central Gereshk district," Bismillah Jan warns.

Shift to Kandahar?

Disagreements and lack of co-ordination are still the overriding issues in Helmand - on both sides. On the government side, many believe the US is not fully committed to weakening the Taliban.

"There are dozens of armed Taliban, often roaming in long convoys in the countryside but the American Apaches won't touch them. They only target a small number in actual fighting," one official said.

But there are also cracks on the Taliban side. Reports about leadership divisions are everywhere in city circles. Tribal politics and the fight for resources are profoundly influencing Taliban affairs, it seems.

Some blame the killing of two influential Taliban commanders, Mehraj and Haji Ismat, by American drones on Haji Manan, the Taliban governor for Helmand who, rumour has it, is working for the US.

Haji Manan's reported disagreement with Taliban leader Haibatullah is another bit of welcome news in Lashkar Gah.

And there is also talk that this year the Taliban will be on the defensive in Helmand and will devote their energy to destabilising neighbouring Kandahar province instead.

Whether that happens remains to be seen - but for people in Lashkar Gah, these are all hints this year may be calmer than last.

- Published23 March 2017

- Published12 January 2017