10 charts: Theresa May's first year as prime minister

- Published

It's a year since Theresa May became prime minister. Few could have predicted that she would end up, 12 months on, with a smaller Commons majority and diminished authority.

Brexit has been the dominant issue of her time in office so far. Having triggered Article 50 at the end of March, kickstarting a two-year timetable before leaving the EU, she called a general election for 8 June, asking voters to strengthen her hand in Brexit negotiations.

Instead, support for the Labour Party jumped and the Conservatives ended up as the largest party but deprived of an overall majority.

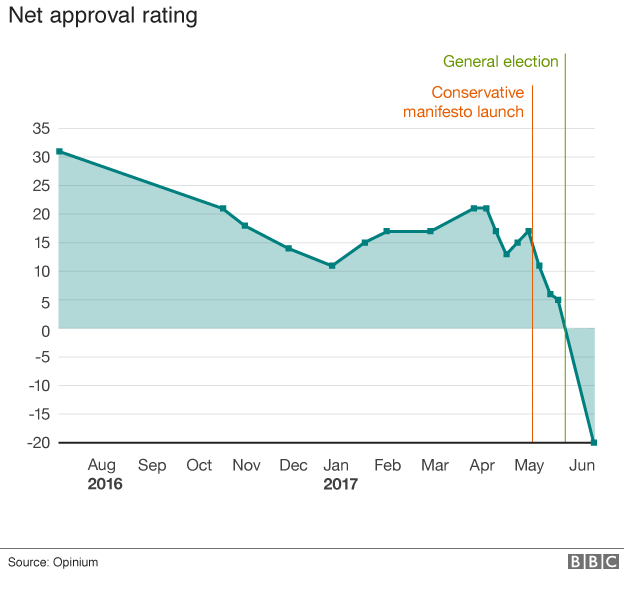

1. Theresa May's popularity has plummeted

When she first took up office last summer, Theresa May was extremely popular.

Her approval rating then fell away a bit, but picked up again in the new year.

In April, with the Conservatives riding high in the polls, the PM felt emboldened to call a general election, despite not needing to do so for another three years.

After a botched U-turn on social care and a widely criticised manifesto, her approval rating nosedived, and fell even further after her party lost seats at the polls.

Now, a majority of the British public think she is handling her job badly.

2. While Jeremy Corbyn's popularity has shot up

Jeremy Corbyn was extremely unpopular when Theresa May became prime minister.

By the time she called the election in April, Mr Corbyn's approval rating had slid even further, making him one of the most unpopular politicians of modern times.

But during the election campaign his popularity improved dramatically, increasing by 39 percentage points between mid-April and mid-June.

June 2017: Jeremy Corbyn addresses Glastonbury festivalgoers

This reversal - and Mrs May's corresponding decline - is one of the most rapid shifts in the history of British political polling.

Now Mr Corbyn has a positive approval rating, meaning more people think he is doing a good job than a bad one.

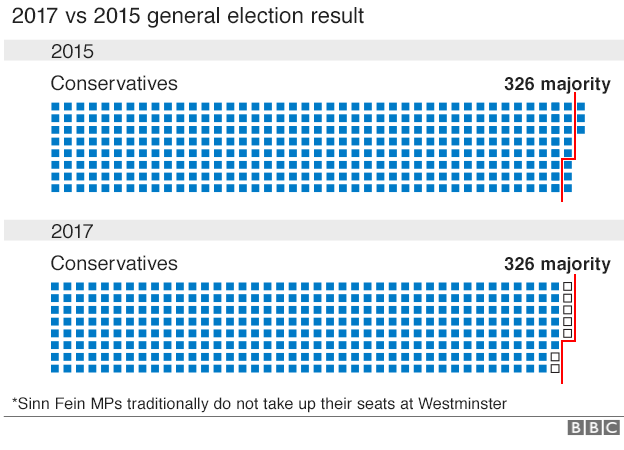

3. The Conservatives have lost their majority in Parliament

The catalyst for the turnaround in the two leaders' fortunes was Theresa May calling the election.

The Conservatives lost the overall majority won by David Cameron two years earlier, confounding opinion polls and political pundits.

They won 318 seats, comfortably more than Mr Corbyn's resurgent Labour Party. But that was 13 fewer than last time, leaving Theresa May just short of being able to form a government on her own.

After more than two weeks of haggling, she signed a confidence-and-supply deal with the Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland, which has 10 MPs.

The general election left Theresa May dependent on the votes of the DUP, led by Arlene Foster

It means the DUP will vote with the Conservatives on key votes - like Brexit - in exchange for more public money going to Northern Ireland.

The parliamentary arithmetic is now very precarious - just a handful of rebel Conservative or DUP MPs could lead to a defeat of the government on key votes.

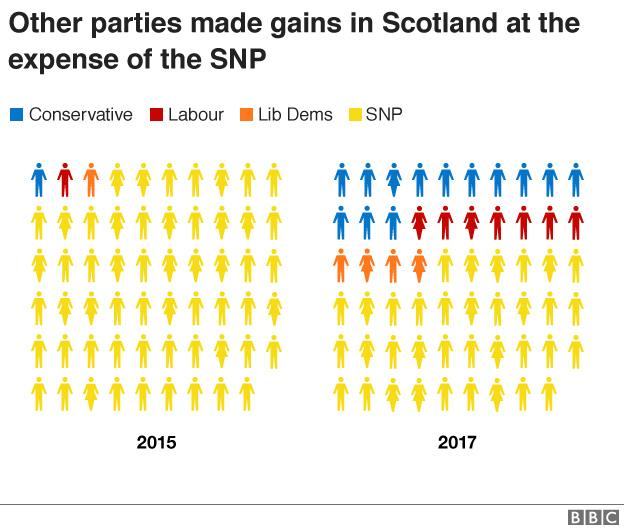

4. Other parties made gains in Scotland at the expense of the SNP

While June 8 was a very bad night for Conservatives in England and Wales, the party did very well in Scotland, winning 13 MPs, up from just one.

This renaissance came at the expense of the SNP, who also lost seats to Labour and the Liberal Democrats.

In March, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon had called for a second independence referendum to take place before the spring of 2019, coinciding with the expected conclusion of the UK's Brexit negotiations.

But following the SNP's setback in June, Ms Sturgeon told the Scottish Parliament she was putting these second referendum plans on hold.

SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon has now put referendum plans on hold

Although the SNP won comfortably more votes and seats than any other party in Scotland, its position is weaker than a year ago, and Scottish independence seems a more distant prospect.

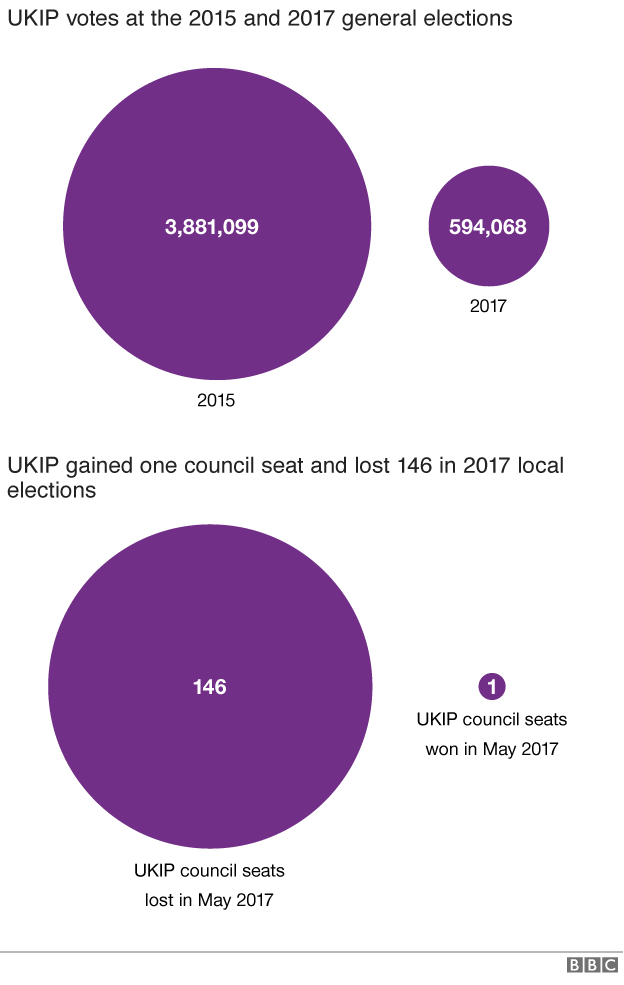

5. UKIP has had a terrible year

If the SNP has had a rough year, the UK Independence Party has had a catastrophic one. Theresa May's tough stance on Brexit has left many questioning the purpose of a party founded to get Britain out of the EU.

UKIP has seen a dramatic downturn in fortunes. It won more votes than any other party in the 2014 European Parliament elections, and almost four million voted for the party in the 2015 general election.

But on 8 June, the party got fewer than 600,000 votes, just one month after a disastrous set of local election results.

UKIP's decline is part of a bigger trend that few people predicted a year ago.

UKIP's leader Paul Nuttall stood down after the 2017 election

More than 80% of voters backed either Labour or the Conservatives in the 1979 general election, but this proportion declined steadily, hovering around two-thirds between 2005 and 2015.

But in June more than 80% of voters backed Labour or the Tories - UKIP was crushed and the Liberal Democrats failed to bounce back from a disastrous showing in 2015.

6. Net migration to the UK has fallen

Net migration - the difference between the number of people moving to the UK and the number of people leaving - has fallen significantly.

A lot of the drop is explained by a decrease in people moving from the EU8 states - the Czech Republic, Hungary, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia - and an increase in people moving back to those countries.

The 248,000 figure is still significantly above the government's target of reducing net migration to the tens of thousands.

However, the fall over the whole year could be bigger than what's been reported so far. There's a time lag of over five months before the data is published so we'll have to wait until December to see the overall change for the last year.

7. Inflation has risen and now outstrips wage growth

The rate of inflation has steadily increased. At 2.9%, prices are going up faster than at any time since June 2013.

One factor behind the rise is the decline in the value of the pound after the EU referendum. A weaker pound makes imports more expensive and pushes up prices.

The weak pound has pushed prices upwards for shoppers

Other countries have also seen slightly higher inflation - partly because of a recovery in the price of oil and other commodities, as well as a small improvement in the global economy. But it's notable that the UK has the highest inflation rate of the advanced economies.

After a few years bumping along below the Bank of England's official target rate of 2%, the recent increase isn't necessarily all bad. But in April inflation overtook wage growth which has now slipped to 1.8%.

That means the UK is back to the situation it faced in the years after the financial crisis. With price increases outstripping wages, workers are getting poorer on average in real terms.

8. Unemployment has continued to fall

There's been better news on jobs. The unemployment rate has been falling steadily for almost six years and that has continued in the past 12 months. At 4.5% it's at its lowest rate since 1975.

There are 32 million people in work and three-quarters of 16-64-year-olds are employed - the highest figure since comparable records began in 1971.

Some other major economies, including the US, Germany and Japan, have even lower unemployment. But the UK is faring considerably better than France, Italy and most other EU countries.

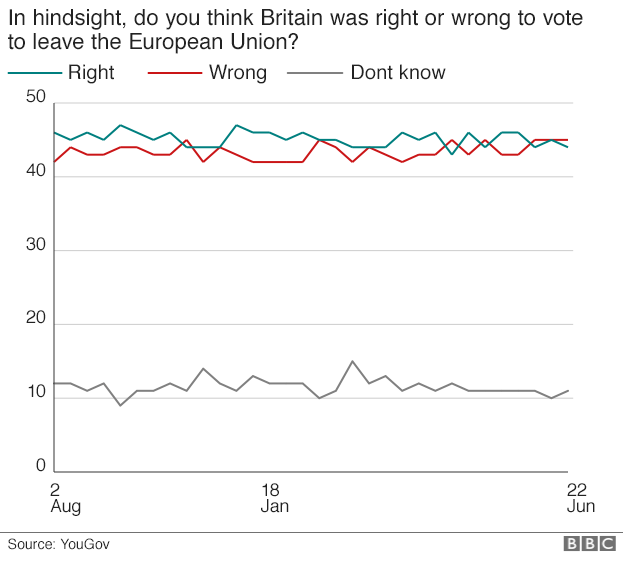

9. People haven't really changed their minds about Brexit

The result of last year's referendum was a 52% to 48% victory for Leave. There's no clear evidence that people's views have changed since then.

YouGov's trend data shows no significant movement since last summer. There's certainly no evidence of a tidal wave of Brexit regret.

And another YouGov poll, external in May found that about half of people who had voted Remain thought the government had a duty to implement the referendum result.

There's little evidence to suggest people have changed their minds about Brexit since the EU referendum

This could change of course. Since the election there have been one or two polls suggesting a small movement away from a pro-Brexit position but not a clear shift.

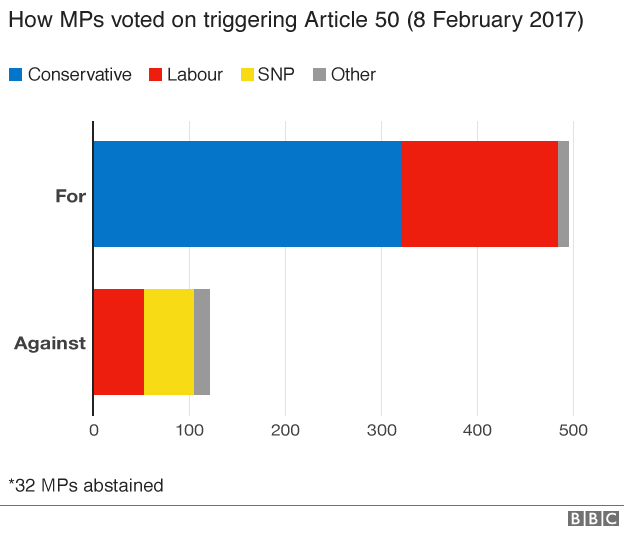

10. MPs voted overwhelmingly to start the Brexit process

At the crucial third reading vote in the House of Commons, MPs voted for the Bill giving the government authority to trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty by 494 to 122.

Almost all Conservative MPs voted in favour - only Ken Clarke voted against - as did most Labour MPs, who were whipped to do so, the DUP, UUP and UKIP's then MP Douglas Carswell.

On the other side, 52 Labour rebels lined up with the SNP, Lib Dems, Plaid Cymru and Caroline Lucas, the only Green Party MP.

The UK's Brussels ambassador delivered a letter from Theresa May to Donald Tusk, the EU Council President, on 29 March, which formally started the withdrawal process. It will last two years unless there's unanimous support for an extension among EU member states.