Obituary: Fenella Fielding

- Published

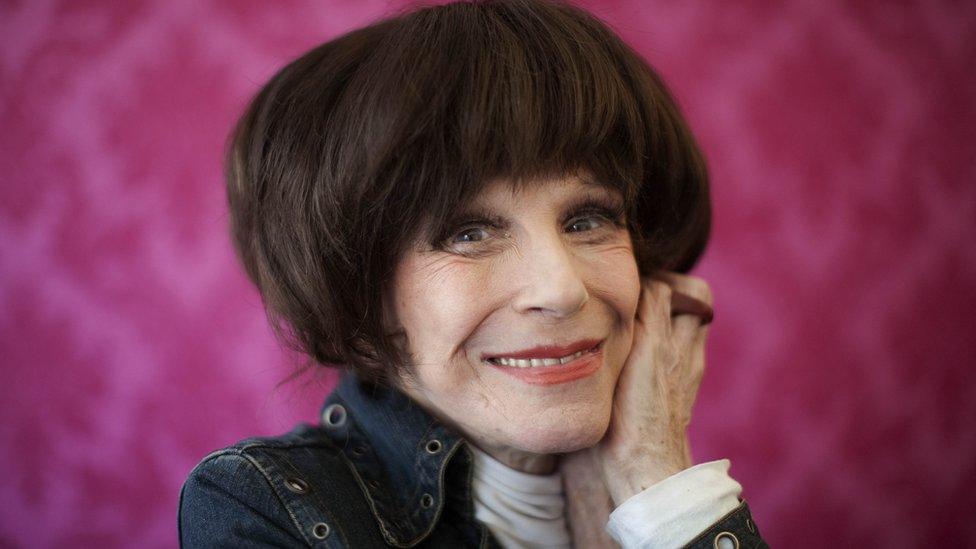

Actress Fenella Fielding has died at the age of 90 after suffering a stroke.

She was a serious actress remembered for a single, stand-out comic performance.

Fenella Fielding survived a violent upbringing to play Ibsen, Shakespeare and Euripides on stage. As an artist, her sheer versatility captivated both Federico Fellini and Noel Coward. This was a woman of wit and wisdom who kept a copy of Plato beside the bed.

But, for millions, that serious side is long forgotten. Instead, she will forever be Valeria: the camp vamp star of Carry On Screaming - draped on a divan in a skin-tight dress; her voice oozing with sex appeal and sporting eyelashes like upturned claws.

She turned down all future Carry On work but the die was cast. In the public mind, she was the quintessential Sixties femme fatale, delivering double entendres with lashings of false innocence. And sadly, as a performer, her career slowly drifted into obscurity almost as soon as she uttered her most immortal line.

"Do you mind if I smoke?" Fenella Fielding with Harry H Corbett in Carry On Screaming.

Street angel, house devil

Fenella Marion Feldman was born in Hackney in 1927 - the youngest child of a Romanian mother and a Lithuanian father. The relationship with her parents was never easy, often strained and occasionally violent.

As a toddler, she seemed to speak in gibberish. Her mother and father worried she was failing to develop normal language skills until they chanced upon her in animated conversation with a doll. "I suppose," she later wrote, "I just didn't want to speak to my parents."

The young Fenella harboured a burning desire to perform. She took ballet lessons and gave her youthful talent for comedy free rein in the annual end of year show - once memorably cavorting around the stage to the tune of Nobody Loves A Fairy When She's Forty.

Other mums and dads, she bitterly noted, showered their children with fresh flowers after each performance; her own parents merely offered up the same basket of artificial blooms, year after year. It was hard not to take it to heart.

As she entered her teens, life at home became darker. Her father - who could be charming in public - was a "street angel, house devil", she recalled who "used to knock me about with his fists".

To make matters worse, her mother would actually "egg him on". She thought the violence would pass, but it didn't - at least until she threatened to go to the police.

She left school at 16 and spent a year at St Martin's School of Art. Her parents were appalled that she might see naked men - or even worse, naked women - in class, which was bound to result in pregnancy and drug addiction. There were rows every morning. Eventually, they forced her to leave.

Still wanting to act, Fielding would hang around stage doors in the West End in the hope of brushing against Alec Guinness or Laurence Olivier. She won a two-year scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art - which pleased her mother and father greatly until it dawned on them she might actually become an actress.

Her mother began turning up at RADA at lunchtime, making a scene and insisting Fielding leave. "Really, darling", she would say, "these common people!" After a while, the school quietly withdrew her funding.

1964: Fenella Fielding joins Noel Coward and other stars of his musical 'High Spirits' at the piano.

She considered going to university but her father told her he'd "rather see her dead at his feet." Instead, she was dispatched to learn shorthand and typing. She found it soul destroying.

In misery, Fielding downed 70 aspirin in a suicide attempt but changed her mind at the last minute. She swallowed pints of mustard water to induce vomiting after calling an all-night Boots to ask how to reverse the effects.

Beautiful butterfly of comedy

Fleeing home, she found digs in Mayfair run by friendly prostitutes. In 1952, she appeared in an amateur production at the London School of Economics alongside Ron Moody - then a mature student - who later found fame as Fagin, in the film version of Oliver!

Fenella Fielding with Norman Wisdom in Follow A Star. She strongly disliked her co-star and found his attitude to women appalling.

Moody supported her ambition to become an actress, persuading her not to pack it in and train as a manicurist. She changed her name from Feldman to Fielding, pretended to be seven years younger in order to compensate for her late start in show business and began appearing in comedy revues.

By the end of the 1950s, she had made a name for herself in the musical Valmouth. It was quirky and, for the time, rather lurid - but Fielding's rave reviews led to an awkward reconciliation with her parents. Her mother turned up at the Lyric Theatre bearing a peace offering of sorts: a whole, fried chicken.

Next was Pieces of Eight, a live comedy revue written by the unlikely pairing of Peter Cook and Harold Pinter. Starring alongside her was Kenneth Williams - already firmly established as a household name - who quickly proved to harbour a brittle ego under the thinnest of skins.

Fenella Fielding starred with Kenneth Williams in both Pieces of Eight and Carry On Screaming. She said Williams often became wildly jealous and threw constant tantrums

When one review called Fielding a "beautiful butterfly of comedy", he exploded. Encouraging her to ad lib, he ruthlessly stole her best lines. He became threatening and bluntly warned her not to steal his limelight.

When Fielding extemporised the end of one sketch with the line "the last one dead's a sissy", there were hysterics. Williams went white and shrieked that she'd "called me a homosexual in front of the whole audience". "It was awful," she later recalled. "I'd never been so frightened in all my life."

Worse was to come as she branched out into film and television. In 1959, she appeared in Follow A Star alongside Norman Wisdom - who she came to loathe. "Not a very pleasant man," she later said. "Hand up your skirt first thing in the morning. Not exactly a lovely way to start a day's filming."

Fielding with Ian Carmichael in The Importance of Being Earnest in the early 1960s.

Socially, the 1960s could not have been more glamorous. Vidal Sassoon, personally, did her hair and the bohemian journalist Jeffrey Bernard took her on riotous club nights. She would sit and talk long into the night with the flamboyant artist Francis Bacon and the rest of that decade's rakish beau monde.

Professionally, there were small parts on television in The Avengers, with Patrick Macnee, and regular appearances on the cutting-edge satire, That Was The Week That Was. Her film appearances included working alongside Dirk Bogarde in Doctor in Love and Tony Curtis in Arrivederci, Baby!

On stage, she pursued her love for her first love, drama. The Times newspaper described her performance as Hedda Gabler as "one of the experiences of a lifetime".

The great Italian film director Federico Fellini took her to Claridge's and offered to make a film where she starred as six or seven different incarnations of male desire. Unfortunately, she was already booked to do a season on stage in Chichester so she turned him down - to the great disappointment of her agent.

Camp vamp

Then came the role which made her a legend. Carry On Screaming reunited Fielding with with her old nemesis, Kenneth Williams. The filming took three weeks, made her hugely famous and - in many respects - her career never recovered.

Fielding had a glamorous nightlife in the 1960s. Vidal Sassoon did her hair and she trawled London's social scene with Jeffrey Bernard and Francis Bacon.

She played Valeria - a thinly disguised Morticia Addams - with every ounce of camp vamp she could muster. Her wig was huge, her eyelashes incredible and her red dress was so tight she was completely unable to bend in the middle. Every scene was done in a single take and, of course, she is remembered for just one.

Reclining on a chaise longue, Fielding entices Harry H Corbett towards her. The eyes flutter and the voice purrs. "Do you mind if I smoke?" she inquires seductively - before vast quantities of dry ice envelope them both.

Half a century later, children would still shout that line at her in the street. She politely declined all invitations to appear in future Carry On films - including Carry On Cabby - partly in an attempt to avoid being typecast by the success of the first. But, for the rest of her life, she struggled to escape Valeria.

The offers dried up and her on-screen career quietly slid away. She did Morecambe & Wise Christmas specials and some voice work for both the cult hit series, The Prisoner, and a Magic Roundabout project - Dougal and The Blue Cat. But she didn't make another film for almost 15 years.

Fielding was rarely completely out of work. She continued on stage - with a string of well-reviewed provincial shows - in which she didn't have to play "either a Lady or a Tart". But, eventually, she struggled for money and was forced to go to the social security office to claim benefits - an experience she found demeaning.

She never married, despite a string of interested male admirers. One possible future husband died, another couldn't get over his alcoholism and had to be abandoned. For 20 years, she maintained two separate lovers and managed to prevent them ever meeting. "I loved them both," she wrote but decided on "never committing; never having a marriage that could have gone awful".

1979: Fielding at a demonstration against a rise in VAT. Politically, she opposed the government of Margaret Thatcher

Politically, she was on the left - despising Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s and refusing to help her older brother Bas when he stood for election under the Conservative banner. But they remained close and she was proud of him when, without her help, he became an important figure in the party and eventually entered the House of Lords.

Latterly, there was work with Rik Mayall and Adrian Edmondson in Guest House Paradiso and a role as an eccentric granny in the gritty teenage drama, Skins. But, for Fenella Fielding, her best work always took place on stage. At the age of nearly 90, the Financial Times described her performance in Euripides' The Trojan Women as "unbearably moving... at the extreme limits of pathos".

For most of the rest of us, however, she is preserved in memory as the camp vamp of Carry On legend. She will forever be "England's First Lady of the double entendre" with a velvety voice and silvery twinkle in her eye.

She was resigned to that professional fate. The autobiography she published in 2017 - inevitably entitled "Do You Mind If I Smoke?" - has little shred of bitterness or regret.

The only thing that rankled was when she met fellow actors - and there were many - who'd been asked to do adverts with a "Fenella Fielding-like" voice.

"Bloody cheek," she would say with perfect comic timing. "Why didn't they ask me?"