Has Fyre Festival burned influencers?

- Published

Expectations....

"Fyre was basically like Instagram coming to life."

Or at least, that was the idea, says DJ/producer Jillionaire in the new Netflix documentary Fyre: The Greatest Party that Never Happened.

The organisers spent eye-watering sums on an extravagant launch campaign with 10 of the world's top supermodels sharing gorgeous promotional pictures and videos of themselves partying in luxurious style on a sun-drenched island in the Bahamas.

Kendall Jenner was reportedly paid $250,000 (£193,000) for one single Instagram post announcing the launch of ticket sales and offering her followers a discount code.

Despite the "luxury" tickets costing thousands of dollars, the event sold out - many snapped up by social media influencers keen to document their exclusive experience, many in exchange for free accommodation.

The festival was supposed to run annually for five years.

However, just like Instagram, away from the filters and the supermodels, the reality turned out to be somewhat different.

... versus reality

The "private jet" in which the guests were supposed to arrive, turned out to be an old rebranded aeroplane. The luxury accommodation consisted of rain-drenched tents, and the gourmet cuisine was a cheese sandwich.

The event never took place.

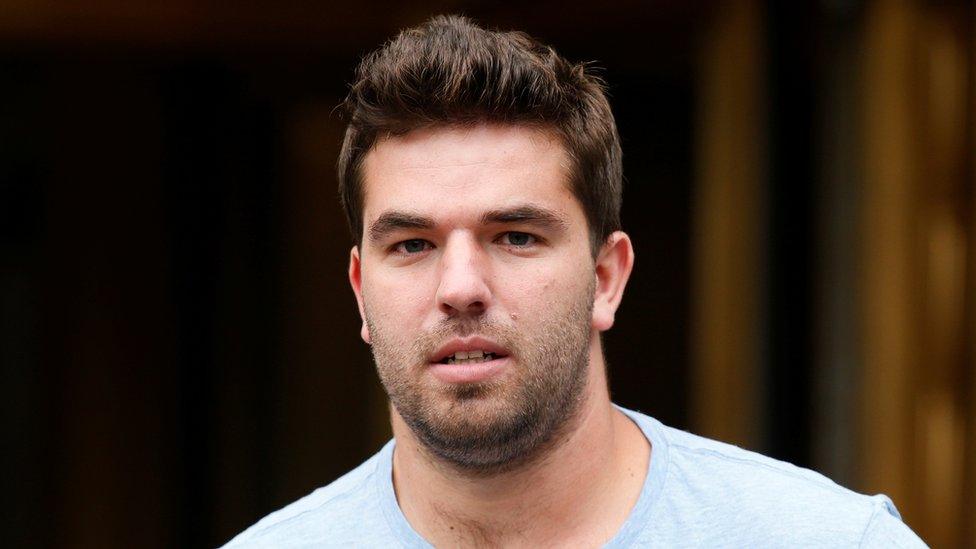

The organiser, Billy McFarland, is now in prison for fraud.

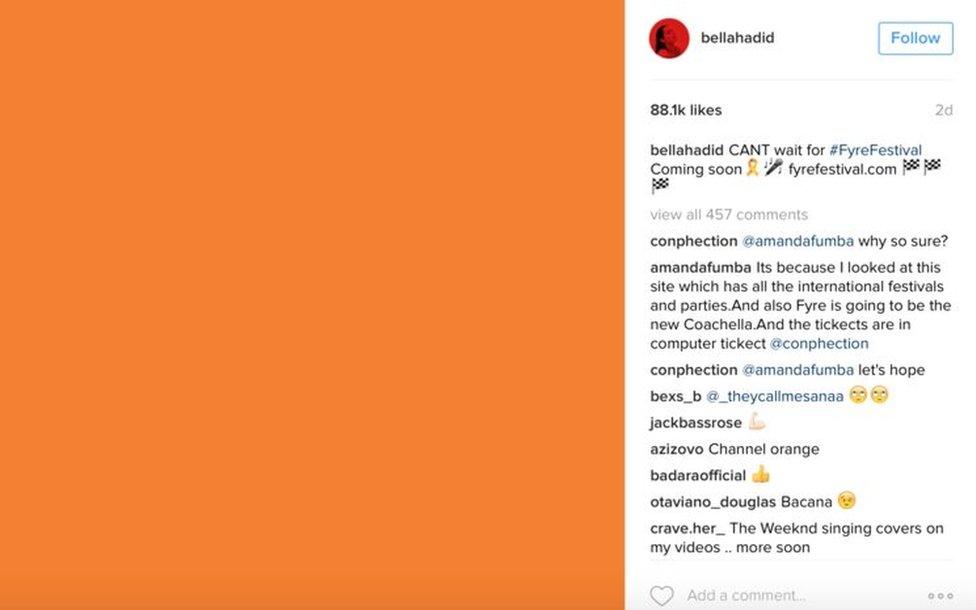

Bella Hadid, one of the models who took part in the promotions, later apologised to her followers and said she had "trusted" the event would be "amazing and memorable".

Kendall Jenner deleted her post.

Two new documentaries about the luxury event that never was - one by Netflix, the other by US streamer Hulu - have thrown a spotlight on the influencers and celebrities who promoted it.

You'd be forgiven for thinking this all sounds like extremely bad news for the influencer industry. But you'd be underestimating their Teflon-like resilience in the face of adversity.

Rapper Ja Rule took part in promotional activity with Billy McFarland

Rohan Midha, managing director of the PMYB influencer agency, says that while Fyre itself was a disaster, the marketing choices behind it were not.

"It just shows how powerful influencers can be," he told the BBC.

On the subject of Fyre, he agrees that while the sheer size of the influencer campaign was "unusual", the results were not.

"Influencers can reproduce the largest return on investment," he says. "That's across the board."

Werner Geyser, founder of the Influencer Marketing Hub, agrees. He says since the release of the documentaries his web traffic has spiked as curiosity in the industry has increased.

"If anything [the Fyre Festival documentary] was showing utilising influencer marketing was part of its success in terms of marketing the event," he says.

"It's all publicity at the end of the day. I think brand managers and influencers will be more cautious and that can only be a good thing."

The Fyre team was keen to promote the exclusivity of the event

Mr Geyser thinks the documentaries will emphasise the importance of regulation - the responsibility of flagging promoted content using hashtags like #ad, #spon and #sponsored.

In 2017, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the US warned celebrities and influencers that they must be clear about when a post has been paid for - but not all of them do.

"Trust is lost when you are selling something that you were paid for but didn't declare," says Mr Geyser.

"If you can say something is sponsored [the consumer] can take it with a pinch of salt."

But do they?

The egg that cracked Instagram

If you doubt the power of a stranger on social media to tell large numbers of people what to do - have a think about this.

"This month we've seen people being influenced by an egg," says Instagram consultant Danny Coy, referring to a picture of an egg which convinced more than 40m people to "like" it on Instagram.

Mr Coy, whose photography account on Instagram has 157,000 followers, is a former influencer himself.

"What's been happening for a while is the rise of the micro-influencer - people who have a much more organic following, less than 10,000, but they are really niche and targeted," he says.

"If you want to geo-locate or target certain areas, brands would rather team up with 10 micro-influencers than one big one."

The firm Neoreach offers data on influencer industry growth. According to its research and forecasts:

The number of Instagram posts using popular hashtags to denote advertising or promotion has risen from 1.1 million in 2016 to 3.1 million in 2018

They predict there will be 4.4 million officially promoted posts in 2019

The average return on investment in 2018 was $5.20 for every dollar spent on influencer marketing, according to a study of 2,000 campaigns

Instagram is the most popular platform for influencer campaigns, followed by Facebook and YouTube

The influencer market size has grown from $1.7bn in 2016 to $4.6bn in 2018 and is forecast to hit $6.5bn in 2019

Bella Hadid was among those who posted an image of an orange square onto Instagram to promote the festival

One expert who is not "liking" the influencer phenomenon is Dr Mariann Hardey, associate professor in marketing at Durham University.

"I would counter that the influencer industry is not successful," she says.

"It appears successful as an extension of aggressive marketing communications and PR methods, but as a standalone, self-sustaining and ethical industry it is far from successful."

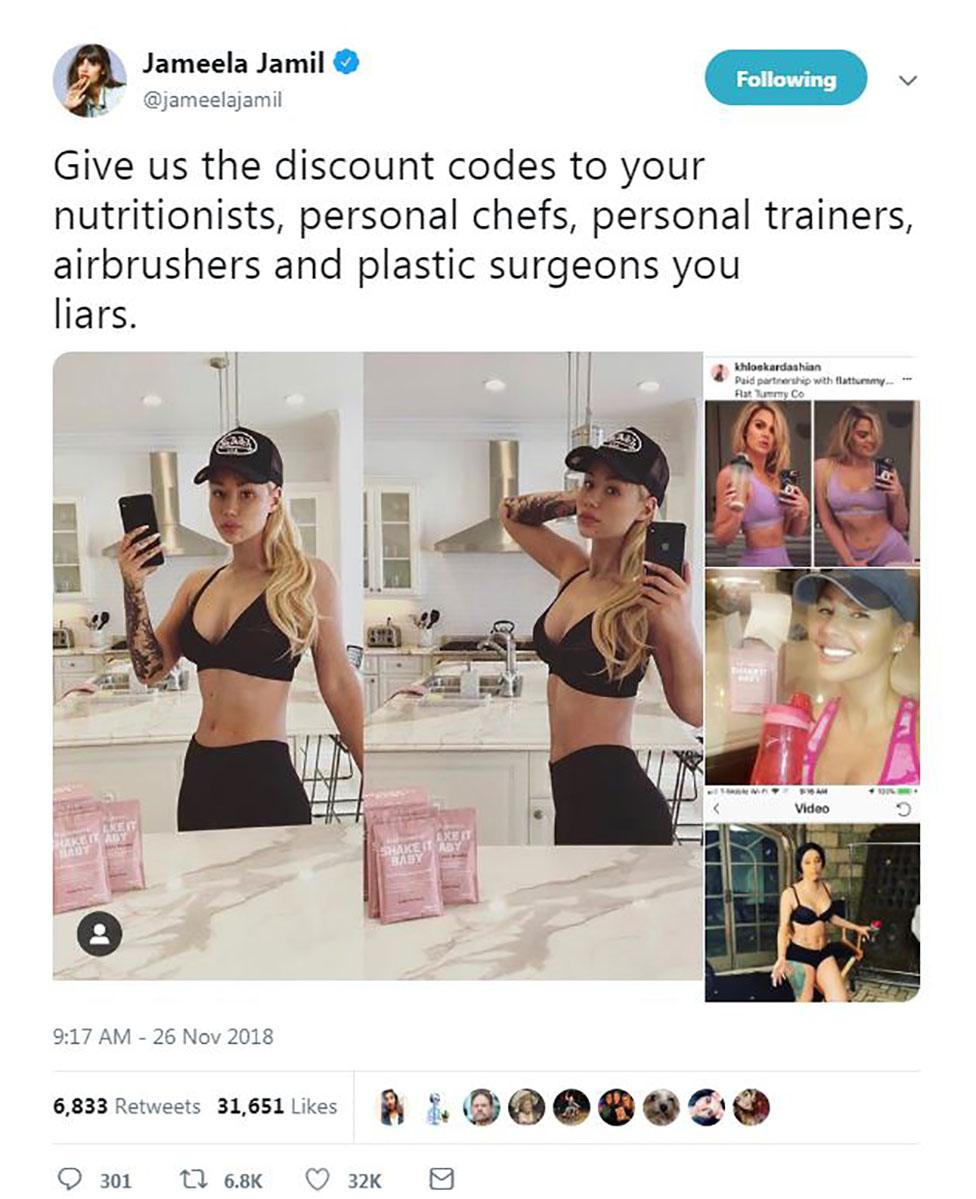

Dr Hardey points out a growing backlash over some influencer-endorsed products such as weight-loss tea amid reports that it can, in some cases, be addictive and even dangerous.

"The backlash against these kinds of products is highly visible - in some cases known more than the influencers involved with the promotion," she says.

This was raised by the actress Jameela Jamil, who started the high profile "I Weigh" campaign, to counter promotional weight loss messages spread by influencers, and to encourage more positive body image.

Dr Hardey believes that influencers are not as powerful as they may consider themselves to be.

"Consumers are smart," she says.

"Overall, relying solely on influencers and the commercial viability of platforms such as Instagram [in a campaign] is precarious at best."

That lesson was learned the hard way by those involved in the Fyre Festival.

"A couple of powerful models posting an orange tile is what essentially built this entire festival," reflects Mick Purzycki, who worked on the festival, in the Netflix documentary.

"And then one kid with probably 400 followers posted a picture of cheese on toast and that trended and essentially ripped down the festival."

Bon appetit

- Published20 January 2019

- Published21 January 2019

- Published11 October 2018

- Published7 March 2018

- Published28 April 2017