General election 2019: What is Labour's four-day working week plan?

- Published

Labour has said it could introduce a 32-hour full-time working week, with no loss of pay, within 10 years. But the Conservatives have attacked the plan, saying it would "cripple the NHS".

So what exactly is Labour's policy and is the criticism justified?

What is Labour proposing?

Shadow chancellor John McDonnell initially set out the shorter working week policy at the Labour Party conference in September:

"The next Labour government will reduce the average full-time working week to 32 hours within the next decade," he said.

In the accompanying press release,, external the party said trade unions would be at the heart of negotiating working pattern changes, eventually leading to a series of legally-binding agreements for different sectors of the economy.

In his speech, Mr McDonnell linked reduced hours to higher productivity - "the link between increasing productivity and expanded free time has been broken".

Labour's working hours policy announcement came after it commissioned a report by Lord Skidelsky, external. It found that capping hours nationwide, along the lines of France's 35-hour working week, was "not realistic or even desirable". Instead, the report said, any cap on hours would have to be adapted to the needs of different parts of the economy.

John McDonnell says the progress to reduce working hours has stalled in recent decades

What have the Conservatives said?

The Conservatives claim that the introduction of the four-day week will increase staff costs at the NHS by £6.1bn a year.

They claim that figures show the average NHS worker does 37.5 hours per week, and earns £32,257.

Reducing those hours to 32 would increase staff costs by 17.2%, they claim. Across a workforce of 1.1 million, that would come to a total of £6.1bn. This is because extra staff would have to be employed to cover the missing hours.

That would effectively wipe out the extra £6bn a year that Labour has pledged for the NHS by 2023-24, the Conservatives argue.

The 37.5 hours total is the standard working week for most NHS staff., external But many of the highest-paid roles, such as doctors and top managers, work significantly more than 37.5 hours a week, so capping their hours at 32 per week could cost even more.

The calculation assumes that there is no increase in productivity associated with shorter working hours.

They also assume that the 32-hour working week would be operational across the entire NHS workforce from the next financial year, which is not what the Labour Party is proposing.

How has Labour responded?

Labour's shadow health secretary, Jonathan Ashworth, has dismissed the Conservatives' claim as "just nonsense".

He says if it wins the election, the party would not immediately bring in a four-day week for NHS workers, which is the assumption the Conservatives have made.

However, the language Labour is using to explain the policy appears to have slightly shifted since September. Speaking on Wednesday, Mr McDonnell said that while the 32-hour working week would apply to everybody, it would only be implemented "over time as the economy grows".

He added: "It's not an overnight thing, but it's a realistic ambition."

Are Labour talking at cross purposes over this?

The Conservatives claim that senior Labour figures have contradicted each other over whether the 32-hour week applies to the NHS or not.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock said in a statement: "Corbyn's health spokesman toured the TV studios this morning claiming that their plans for a four-day working week would not apply to the NHS. But now the shadow chancellor says it will after all."

So what did they actually say?

On Wednesday's BBC Breakfast, Mr Ashworth said: "It's not happening - there's not a four-day week coming in the NHS."

But Mr McDonnell also said on Wednesday: "It's a 32-hour working week, implemented over a 10-year period. It will apply to everybody."

Shadow health secretary Jonathan Ashworth says Tory claims are "ridiculous"

Despite the apparent contradiction, the two statements are broadly consistent. Labour is not planning to impose a 32-hour week in the NHS in the months after the election, if it comes to power.

It is a target for the average working time across the whole economy - including the NHS - to be achieved over 10 years.

If the NHS - like other sectors - does not improve productivity sufficiently, it would not achieve a 32-hour week.

Do Labour's own documents say the 32-hour week will hit the NHS?

Mr Hancock also claimed: "Labour's own policy documents say that their plans will hit hospitals and impact staff numbers."

The claim is based on the Skidelsky report, which draws lessons from the implementation of the 35-hour week in France.

The report says: "The introduction of the 35-hour week in hospitals caused particular problems because it was done without proportional job creation, and productivity gains cannot easily be made in hospitals."

Labour is not proposing to introduce a 32-hour week in the same way, so the implications for its proposals are limited.

Are Labour's plans achievable?

Labour's 32-hour week plan is based on the UK economy becoming more productive.

For decades, the UK was successful at increasing productivity, as new technologies such as computers allowed workers to get more done. Many of those gains have been taken in the form of shorter working hours.

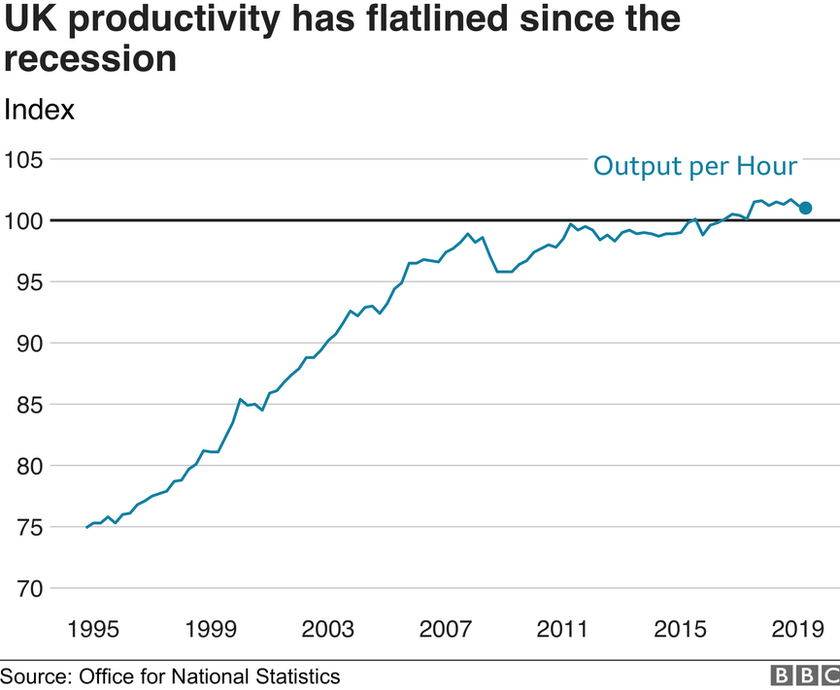

However, as this chart shows, productivity in the UK has increased little since 2008.

There is no economic consensus about why this has happened, or how to address it - it's known as the productivity puzzle.

Labour has plans for how to improve productivity, such as investing more money in education and training. Those plans will have to deliver a significant improvement on the recent trend to make Labour's 32-hour week possible.

- Published12 September 2019

- Published21 November 2018