The assassination of a ‘Brave Journalist of Afghanistan’

- Published

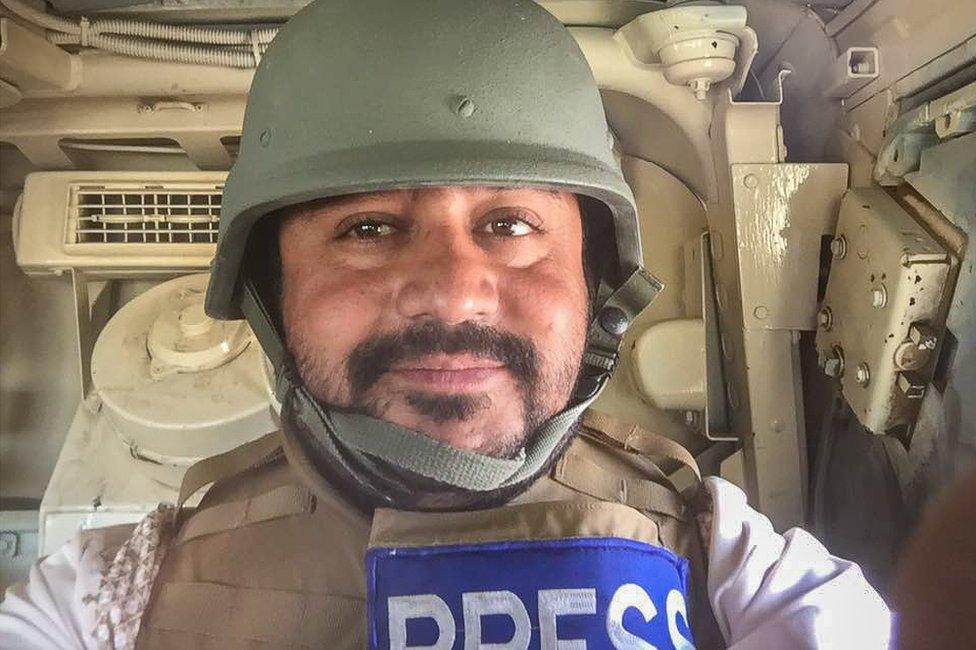

Aliyas Dayee often travelled to the front line in Helmand to record his daily radio reports

The night before he died, Aliyas Dayee was up late working. This was not unusual for Dayee, who didn't mind going to bed late or getting up early for a story. That night, he was finishing a radio report about an attack on an Afghan military checkpoint near Lashkar Gah in Helmand province, Afghanistan, where he lived.

Dayee, who was 33, was born and raised in Helmand and spent his working life covering the ebb and flow of violence between the military and the Taliban. In the months leading up to his death, the violence had been flowing. Even as peace talks got under way thousands of miles away in Qatar, with the aim of ending the war, Afghanistan was experiencing a surge in assassinations of people in public life.

Dayee eventually closed his laptop and went to bed, and in the morning he and his brother Mujtaba set off early to collect a Danish journalist he was helping with a radio report. Dayee had recently purchased a new car so he could drive his elderly mother to the hospital in greater comfort. He was diligent about checking its undercarriage for explosives - getting down on all fours no matter how short a time the car had been left unattended. His friends would joke to him that he was like a mouse - always alert, ready at any moment to dart away from danger.

The shopkeepers opposite Dayee's house said that he checked the car as usual that morning. But a magnetic "sticky bomb" had been placed inside the wheel arch, police told the family, where it was hard to spot, and it detonated shortly after the two brothers left the house, killing Dayee and wounding Mujtaba. Dayee's wife heard the explosion from the house and went running.

Afghan security officials surround the wreck of Aliyas Dayee's car in Lashkargah

The blast did not come out of the blue. Dayee had received shadowy threats over the years from the Taliban, often by way of the security services - enough for his employers at Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) to fly him several times to Kabul for his safety.

Recently, his family had tried to persuade him to move to the capital. For months, the Taliban had been pushing towards Lashkar Gah from surrounding districts and in October the militants were closing in on the city.

The day before he died, Dayee texted his friend Aziz Tassal, a Washington Post journalist he had known for 15 years, to say he was worried and thought he should go to Kabul. Tassal had often urged him to leave Helmand. "Three or four times he went to Europe for work, and every time I begged him to ask his managers if he could stay," Tassal said.

But Dayee resisted. "Helmand is my soul," he told his friend. He did not want to leave his mother, wife and their young daughter, or his sister and her children who he had taken in when her husband, a policeman, was killed. He had also recently pitched a large tent in his garden to offer shelter to four other related families displaced by the fighting, and they had to be thought of too.

Dayee's younger brother, Mudassir Dawat, was not in Helmand the day his brother died. He had followed Dayee into journalism and was in Kabul for a conference. It was too dangerous to return to Helmand by road, so Dawat could not get back in time to see Dayee laid to rest. A few days later, he sat down and opened the laptop his brother had been working on the night before the bombing. On the screen was Dayee's audio editing software, open on his final report. Dawat pressed play, and heard once more his brother's warm voice, speaking to an elderly man displaced by an attack that day.

"My body was shaking when I played it," Dawat said. "It was his last work. His last voice."

When it was over, he carefully paused the recording and left the software open.

Dayee posing with local children in government-controlled Kajaki

Dayee had been working for RFE/RL - known as Radio Azadi in Afghanistan - for 12 years before his death on 12 November. His rich, made-for-radio voice was known around Helmand, it reached into homes and told stories of war; stories of the ever-present drug trade; stories of society and culture.

"Everybody knew his voice," said Tassal. "A lot of places in Helmand there are no TVs, only radio. I used to tell him, Dayee you are like bread, you are in every home."

Dayee was also an indispensable resource for many of the international reporters and researchers who travelled in and out of the province as the news came and went.

Photojournalist Andrew Quilty began working with him in 2016 and kept working with him on and off for four years, developing a friendship. The two met in Lashkar Gah last month to conduct interviews for Quilty's podcast, Afghanistan after America.

"I would say 95% of stories, documentaries, media of any kind that came out of Lashkar Gah in the past four or five years had his fingerprints on them," Quilty said. "I find it hard to imagine how his absence will be filled."

Ashley Jackson travelled with Dayee while researching a PhD in the region in 2017. He was "dangerously funny" she said. 'He would say things no-one else would say".

"I absolutely wouldn't have been able to do that work without him. It's just not possible to report on this world without Afghan reporters who know what they're doing."

A selfie taken by Aliyas Dayee while travelling with Afghan security forces

Dayee's assassination leaves behind a dark spot in Helmand. No group has claimed responsibility for the bombing, but observers believe the Taliban are most likely behind the recent spate of assassinations. The killers have targeted independent voices - journalists, rights activists, politicians, and people who have championed advances in women's rights since the Taliban was toppled by US-led forces in 2001.

Dayee was 14 then, when the Americans arrived. He grew up in Chah-Anjeer in Nad-e Ali district in Helmand - a village named after a fig tree and perpetually caught in the crossfire through shifting wars. His father's 5400 Afs ($100) monthly salary was stretched thinly over 25 family members, rarely allowing for luxuries like pens and notepads for school. All his life in Afghanistan Dayee saw violence - his early years marked by the chaotic power vacuum left by the Soviets; his pre-teen years by Taliban rule; and his young adult life by the ravages of the US invasion and Taliban insurgency.

After finishing secondary school, he embarked directly on a career in journalism, fashioning himself into an intrepid reporter and becoming a face locally around Lashkar Gah.

"Dayee was a typical village boy, but his curiosity, contact-making and journalistic skills soon made him stand out," said Auliya Atrafi, a former BBC journalist who grew up in the same village and was taught English by Dayee's father. "His father was an independent spirit with a tendency to look at the world in an interesting, critical way, and Dayee inherited that," Atrafi said.

Sami Mahdi got to know Dayee later, eventually managing him when Mahdi became Kabul bureau chief for RFE/RL in 2019. "He was a wonderful soul and he had a high sense of humour," Mahdi said. "Despite the ongoing conflicts he always brought new ideas, produced human interest stories. He was so accurate, and he presented his reports with this powerful, warm and influential voice."

Dayee, left, with Afghan soldiers in Helmand. He risked his life to report, friends said.

Dayee also felt compelled to be close to the action, despite the danger. "He was an unsettling reporter to be around - a freethinker and risk-taker," Atrafi said. "He always pushed the boundaries, went to the frontline."

He would sometimes text his friend Aziz Tassal to say he was with the security forces, close to the fighting, and ask him to take care of things if anything went wrong. "We joked together always," Tassal said, "but sometimes the joke was very serious."

In 2017, Dayee's courage was recognised in the "Brave Journalist of the Year" category at the Kabul Press Club awards. The category is dedicated to the memory of BBC reporter Samad Rohani, who was also killed in Helmand, in 2008 - a stark reminder that life expectancy for brave journalists in Afghanistan can be short.

And things appear to be getting worse. According to local press freedom group Nai, the past five years have been the deadliest on record for journalists in Afghanistan, with at least 65 killed since 2016. Just five days before the assassination of Dayee, another sticky bomb killed three employees of Afghanistan's central bank as well as Yama Siyawash, a famous news anchor who had previously worked for the Tolo News channel.

A few months before he died, in July, Siyawash sat down for an interview with Tolo TV, the entertainment branch of the channel. "Journalism is a minefield," he said. "And a mine can get you at any moment."

Aliyas Dayee at the 11th-Century city of Qala-e Bost, near his home in Helmand

Assassinating a journalist is a brutally effective way of silencing one voice and cowing others. Dayee's murder was "not only a blow to international coverage but to local coverage too," said Andrew Quilty. "Those who have survived are rightfully very concerned now about the viability of working as an independent journalist down there," he said.

The assassination comes at a precarious time for the country as a whole. Outgoing US President Donald Trump plans to drastically draw down American troops in Afghanistan and the Taliban is tightening its grip on cities. The militants pledged in a deal with the US in February that they would stop terror groups like al-Qaeda operating in the country, but a UN official told the BBC recently the two groups were still working closely together. There are fears the national government is losing control.

Dayee was seeing this shift close up. Waves of displaced families were arriving in Lashkar Gah as the Taliban pushed into surrounding districts, and the final interview he conducted with Quilty was punctuated by steady gunshots.

Last year, he bought a plot of land between Lashkar Gah and Chah-Anjeer, where he grew up. He had purchased some livestock and begun to plant an orchard. His old friend Aziz Tassal wondered if he was contemplating a safer way of life. In May, he invited Tassal to visit the plot, and the two men sat there and talked for a while.

"He had planted some few plants there already - peach trees. He said to me, 'Next year you will come here and you will see a lot of trees, and we will eat the fresh fruit.'

"He was unique in humour, unique in word, unique in friendship," Tassal said. "The day he died was a black day for Helmand."

Dayee at work in Helmand province, where he lived all his life.

For his family, Dayee's death is an incalculable loss. He was a role model to many of his nine brothers and 13 sisters, his brother Dawat said. He pushed them to study, to find careers.

"He encouraged us all to finish higher education. Some of our sisters older than him are not educated, but all those younger than him are educated," Dawat said.

"He had the opportunity to go anywhere but he stayed. His heart beat for Helmand and its people. He always said, 'I was born here, I work here, and I will die here.'"

Dayee was buried on the day he died, in a cemetery plot in Lashkar Gah. His mother, wife and one-year-old daughter visited the grave after the short burial ceremony. His daughter has lost her father before she can understand that he is gone. She had become quieter since his death, Dawat said. In the evenings now she goes to her grandmother and points to the phone and says one of the few words she has learned: "Dayee." Her name is Mehrabani. Dayee chose it. It means "kindness".