Brexit trade deal: What were the big themes in the talks?

- Published

A post-Brexit deal has been agreed between the UK and the EU. The rules that will govern how both sides trade with each other in future - and so much more - have been outlined in hundreds of pages of dense legal text.

It will be scrutinised to see who has given ground and in what areas.

We don't have all the answers yet, but we do know that - despite this agreement - lots of things are going to change anyway.

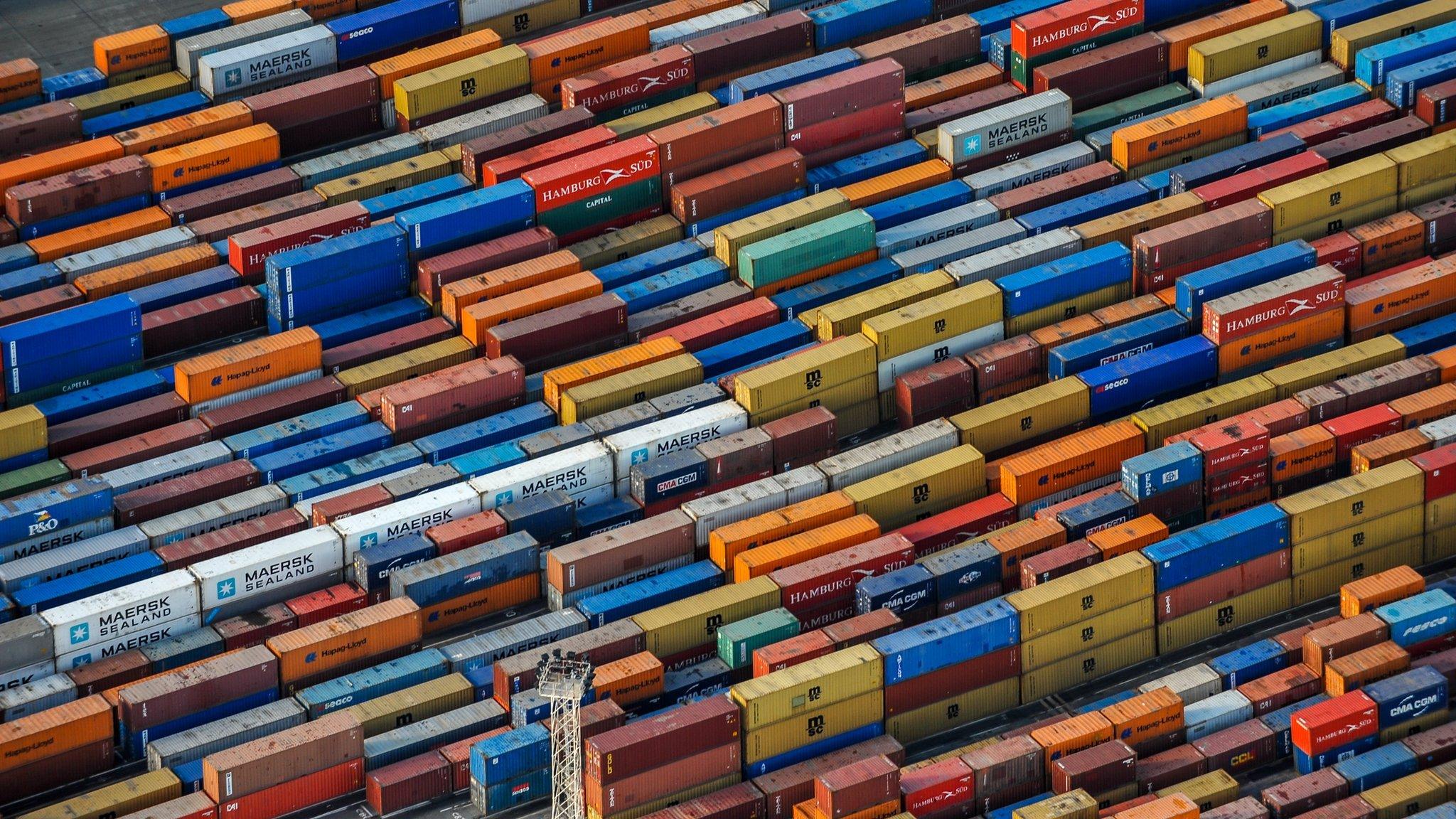

1. More barriers, more red tape

A new era begins on 1 January 2021, ending the relationship which has existed between the UK and the EU for nearly fifty years.

In general, there will be more barriers between them.

The UK will no longer be part of the EU's economic zone - the single market and the customs union - and that means there will be a lot more bureaucracy and delay for businesses and travellers crossing the border.

The UK is introducing a new immigration system which means that free movement of people to and from the EU comes to an end.

EU citizens will no longer have the automatic right to settle in the UK, and British citizens will lose the automatic right to live, work and retire in the rest of Europe.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

The UK will stop making annual budget contributions for membership of the EU, but it will continue to pay much smaller amounts as part of the financial settlement (or divorce bill) for a number of years.

It will also have to pay for any access it wants to European programmes, in fields such as scientific research.

2. Life outside the customs union

This is not a normal trade agreement.

Trade deals are designed to make trade easier and cheaper, by bringing countries closer together.

This one is pushing the two sides further apart. It ends frictionless trade between the UK and its largest trading partner, creating extra costs.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

Outside the customs union, on the other hand, the UK will be able to negotiate its own trade deals around the world.

The government says this is one of the big benefits of Brexit - the UK will be more nimble, able to make its own sovereign decisions.

But any gains will be limited. New deals - over the next few years - will not replace trade that will be lost with the EU.

The independent Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts that over the long term, the UK economy will be 4% smaller, external with a new trade deal - than it would have been if the UK had stayed in the EU.

That's a bigger long term hit to the economy than the one caused by Covid-19. But with no deal at all, it would have been even bigger.

3. A post-Brexit deal against the odds

Despite the limitations set by the clock, negotiators on both sides have done an incredible job in achieving so much in such a short time.

Some people thought it couldn't be done. Agreements of this kind normally take years to negotiate.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

But it isn't a particularly ambitious deal for neighbours that do so much trade with each other. Scope for closer cooperation was limited by the UK government's decision to break away from EU rules as much as possible.

The UK's ambitions lie elsewhere.

For three years after the 2016 referendum, arguments swirled in the UK about whether the country should pursue a soft or a hard form of Brexit.

Both sides agree that this is about as hard a Brexit as you can get, while still having a deal.

A softer form of Brexit - leaving the EU but staying in the single market, for example, like Norway - was debated in parliament but never attracted majority support.

Boris Johnson campaigned in the 2019 general election on a harder form of Brexit and won.

Earlier government promises that the UK would have 'exactly the same benefits' as it had inside the EU have not been delivered, and they never could have been.

4. Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland will have a different relationship with the EU than the rest of the UK from 1 January, because it will remain in the EU single market for goods.

That was part of the plan contained in the Brexit withdrawal agreement to keep the Irish land border between Northern Ireland (in the UK) and the Republic of Ireland (in the EU) as open as it is now.

Earlier this month EU and UK negotiators reached a separate agreement on how this will work in practice.

People protesting between Newry and Dundalk about a possible hard border, in March 2019

Goods manufactured in Northern Ireland will continue to have seamless access to the EU, but as a result new bureaucracy will emerge within the UK between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

There will be document and physical checks on some food supplies, for example (although a three month grace period will begin on 1 January for many traders, before new measures are applied in full).

Pets being taken from Great Britain into Northern Ireland will also need an animal health certificate from a vet.

And because Northern Ireland is being treated differently, this agreement could have longer term constitutional significance for the UK.

Pro-independence politicians in Scotland will continue to ask why, if Northern Ireland can stay in parts of the single market, Scotland can't do the same.

5. Think it's all over?

Just because a deal has been done, don't assume everything is settled. The UK is going to be negotiating with the EU for years to come, on a more or less constant basis.

Resolving disputes as they arise will be a persistent focus, and a likely cause of tension. Arbitration systems will probably be tested to the limit.

It's also worth remembering this deal is not just about trade.

As the name suggests, it is a partnership agreement, involving all sorts of other issues such as road transport, aviation, climate change policy, and security cooperation.

The UK will lose full access to a series of EU databases which police forces use on a constant basis - to check on things such as criminal records, fingerprints and lists of wanted or missing people.

It won't lose access altogether, which would have happened without a deal. But security officials on both sides may well press for ways to improve cooperation in the future.

The agreement on Northern Ireland will also come up for review in four years' time.

So the talking isn't going to stop.