Brexit: Are freight exports to the EU back to normal?

- Published

The government says the volume of freight exports from Great Britain to the European Union has returned to normal, in spite of the new post-Brexit barriers to trade with the EU, and restrictions related to the pandemic.

"The latest available data shows that overall freight volumes are back to their normal levels," a government spokesman said.

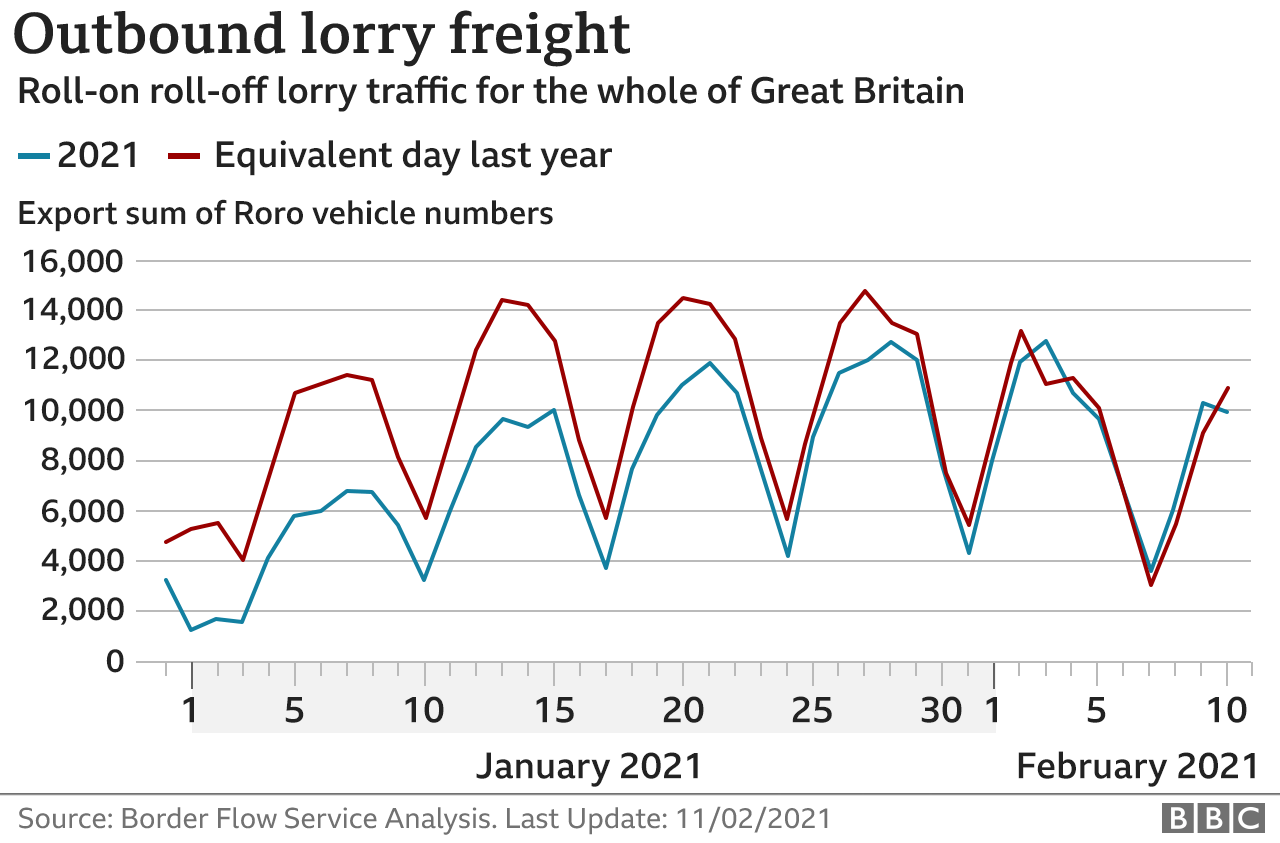

Its internal data shows that the flow of roll-on roll-off freight (which can be driven on and off a ferry or a train) going to the EU in early February was at 98% of the levels seen during the same period in 2020.

But beneath the headline claim the picture is more complicated, with a much larger number of lorries returning to the EU empty in 2021. That means the value of freight exports so far this year will have fallen.

In addition, comparisons with the same period last year are not ideal, because it also saw disruption of normal trade patterns, as the UK prepared to leave the EU.

Dover to Calais

Government data shows that the number of lorries crossing from Britain to the EU is now close to what officials would expect. But if far more of them are empty, that doesn't help very much.

The government's definition of volume of trade includes lorries that are empty.

The most important route for trade with Europe is between Dover and Calais (known as the Short Straits) - both the sea route and the Channel Tunnel.

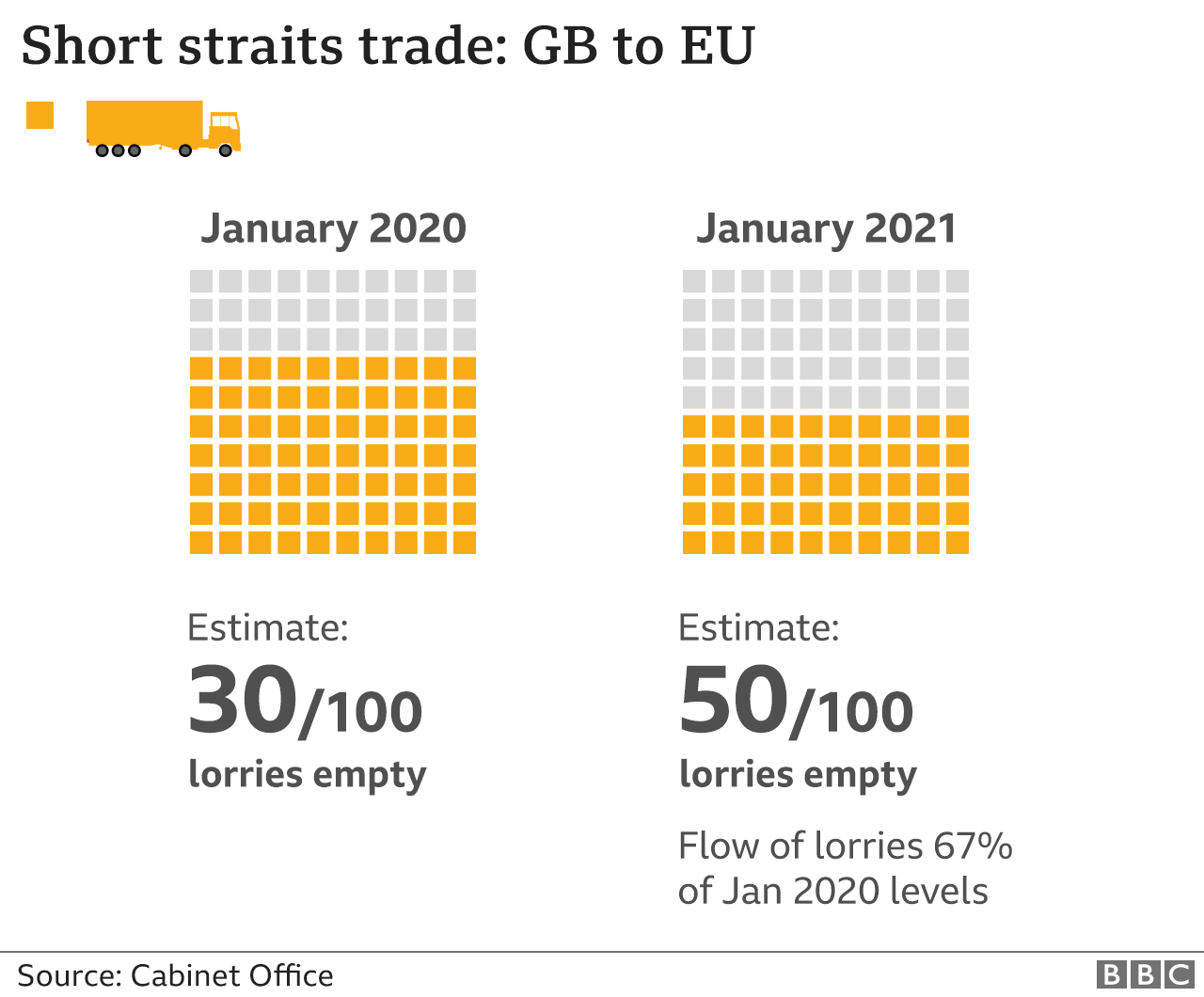

At the start of the year trade was down sharply, but it is improving. The Cabinet Office says the outbound flow of lorries across the Short Straits in January was 67% of 2020 levels, and in the first half of February it was 85% of 2020 levels.

That's still quite a significant fall, but things are clearly getting better as many businesses adjust to the new red tape and costs for trading with Europe.

Covid restrictions have played a big part in the slow start to the trading year as well. There was also significant stockpiling in December, as businesses prepared for the changes with the EU.

Empty lorries

The government calculates that in normal times, about 30% of lorries which have brought goods into the UK from the EU return empty.

So far this year, this number has risen to about 50% - but it is now beginning to fall.

When it comes to the Dover to Calais route, using the government's own estimates to make a rough calculation, the number of full lorries carrying exports to the EU in January was about half what it was a year earlier.

The calculation for the first half of February is better (over 60% of last year's figures), and the government is confident the numbers will improve.

But we will have to wait until March to get official trade statistics for January, which will give a precise picture of the value of exports to Europe.

In the end, the value is more important than the volume.

Other ports?

If the number of lorries crossing the Short Straits has fallen, does that mean they are heading for alternative routes?

Last year, the Department for Transport did buy space on ferry routes from eight other British ports including Harwich, Portsmouth and Tilbury, in case there was Brexit-related disruption on routes from Dover.

Thankfully that disruption has not taken place, and most of the extra capacity has not been needed.

Brittany Ferries, which runs a number of routes from Portsmouth to France, says it saw a sharp fall in freight trade in January. Volumes in February have improved, but they are still down significantly compared to last year.

There have been suggestions that ports such as Immingham and Harwich have seen an increase in export volumes, but neither of the companies running the two ports wanted to comment.

Any comparison with trade flows from Harwich last year would need to take account of the fact that in January 2020 one of the four ferries sailing out of the port was out of service, so it was only running at 75% of normal capacity.

Comparing trade flows with 2020 - in the midst of a global pandemic - is challenging and several industry sources point out that last year may not be a reliable benchmark anyway.

"Making comparisons with a steady state is complicated as each January of the last couple of years has seen some sort of impact related to Brexit preparations," said a spokesman for Eurotunnel.

Back to normal?

All in all, though, it is rather hard to say that Britain's export trade to the EU is back to normal.

The government is justifiably relieved that the reasonable worst case scenario, external it published last year, which highlighted the possibility of queues of thousands of lorries on motorways in Kent, has not come to pass.

Businesses have been better prepared than that scenario envisaged.

"This has been possible thanks to the hard work put in by traders and hauliers to prepare for the end of the transition period," a government spokesperson said.

But in some specific industries, particularly those involving the export of fresh food, the new post-Brexit restrictions are threatening the future of businesses which were already struggling to survive the pandemic.

All these challenges are related to exports from GB to Europe. But from 1 July, imports from the EU are due to be subject to similar post-Brexit border checks and bureaucracy.

And there are already calls for the government to extend the deadline, to give businesses more time before these additional checks begin.