Covid-19 vaccinations: African nations miss WHO target

- Published

The WHO wanted 40% of the world fully vaccinated by the end of 2021

A target for achieving full vaccination rates of 40% in every country by the end of December has been missed across most of Africa.

The World Health Organization (WHO) put forward the goal earlier this year, but only about 9% of people on the continent have been fully vaccinated against Covid so far.

These low rates of vaccination have been of particular concern following the identification of the Omicron variant in South Africa, and its rapid global spread in recent weeks.

Which African countries reached the target?

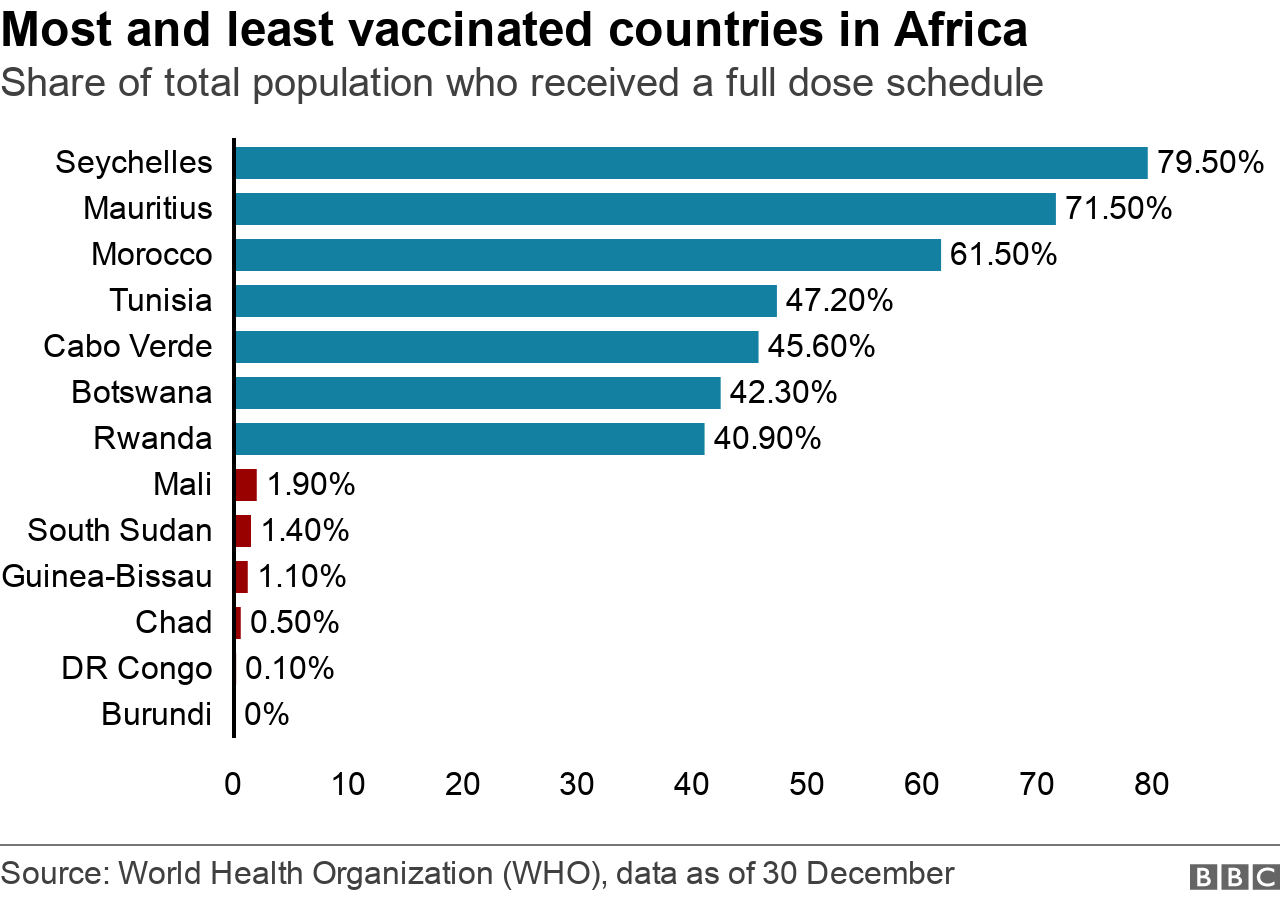

Just seven countries on the continent have reached the 40% target.

Three of these are small island nations where the logistical challenges are much easier to overcome. Seychelles and Mauritius have fully vaccinated more than 70% of their populations, Cape Verde around 45%.

Of the countries on the mainland of Africa, only Morocco, Tunisia, Botswana and Rwanda have exceeded the target.

Countries in the south of the continent are doing considerably better than elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa.

As of 30 December, just under half of the countries on the continent had achieved more than 10% of the population fully vaccinated (a target the WHO had set for the end of September, and which was missed by most African nations).

Many countries, including some of the continent's largest, have so far vaccinated fewer than 5% of their populations.

Nigeria has fully vaccinated 2.1%

Ethiopia 3.5%

Democratic Republic of Congo 0.1%.

The only country on the continent not to have begun a vaccination programme is Eritrea.

The WHO has set a further target of 70% coverage for all countries by June 2022, but this could also be missed across Africa. "As things stand, predictions are that Africa may not reach the 70% vaccination coverage target until August 2024," WHO Africa regional director Matshidiso Moeti says.

Rwanda is one of the few African countries that's met the 40% target

Why are African countries struggling with vaccinations?

Poor health infrastructure, a lack of funding for training and deploying medical staff, as well as vaccine storage issues have all played a part.

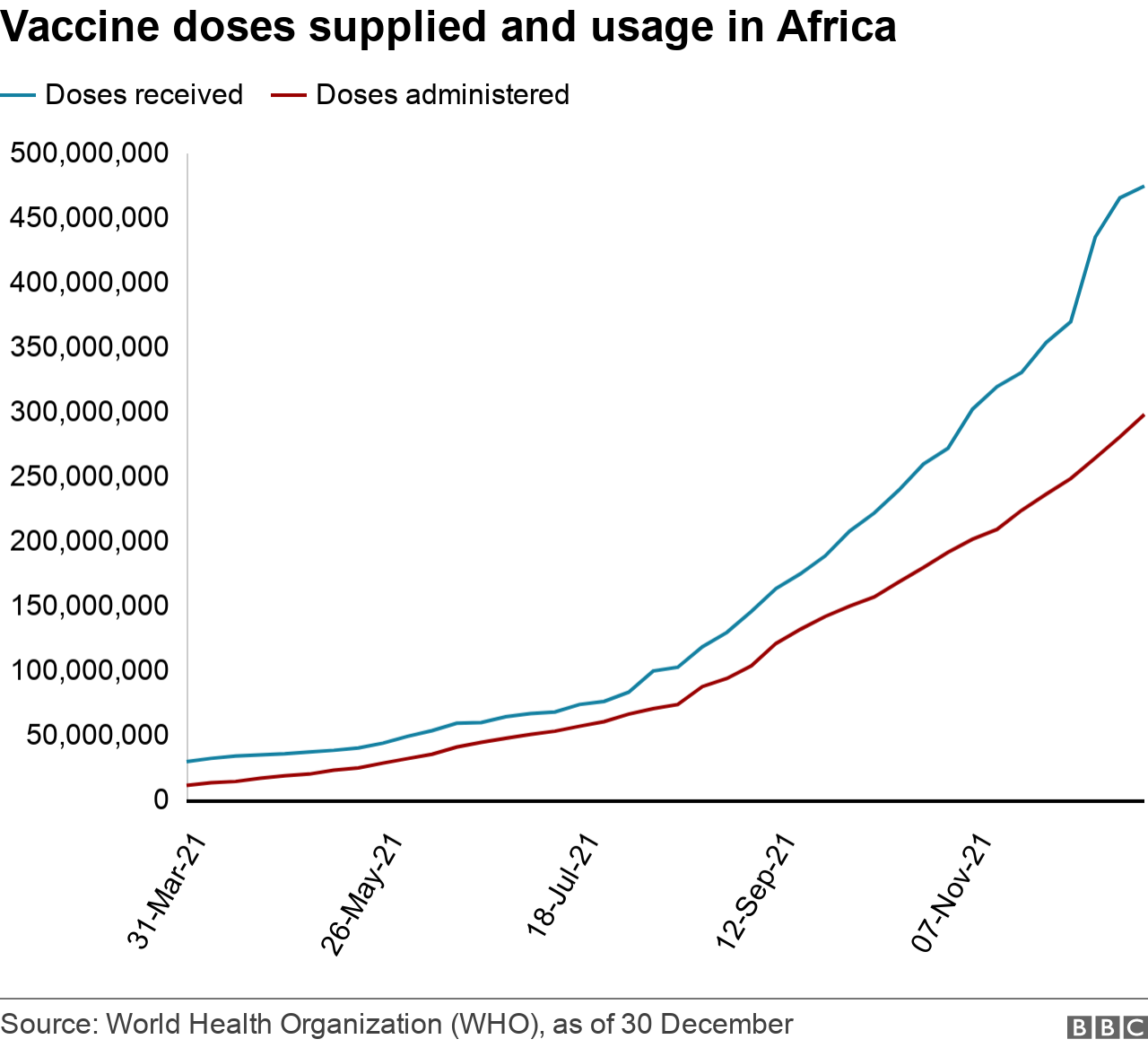

This has become more of an issue because although global supply has improved, distribution and administration of vaccines in some parts of the world are lagging behind.

The WHO and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have expressed concern that some donated vaccines have been delivered with little notice and with short shelf lives.

They want vaccines to have a minimum of two and a half months of shelf life on arrival, and for countries to be made aware a month before delivery.

DR Congo has struggled to deliver vaccines, with just 0.1% of its population fully dosed

There are also fears that vaccine hesitancy and scepticism could be playing a role, although it can be hard to quantify the impact. In November, the WHO highlighted relatively low rates of vaccination among Africa's health workers, which it said was likely to be in part because of vaccine hesitancy as well as availability and access.

Challenges with vaccine supply

African states have relied on a combination of bilateral deals and donations, as well as the global Covax vaccine-sharing scheme, which is intended to help poorer countries get vaccines.

Many countries early this year struggled to get supplies, although the situation has improved markedly over the past few months. Wealthier countries announced donations via Covax - or directly to African nations - at the G7 summit in the UK in June.

The problems faced are now more to do with the logistics of delivery within country, rather than the supply of the vaccines themselves.

"With supplies starting to increase, we now must intensify our focus on other barriers to vaccination. They include lack of funding, equipment, healthcare workers and cold chain capacity along with tackling vaccine hesitancy," says Matshidiso Moeti.

Of the vaccines supplied so far to Africa, 63% have been administered. However, around half of the countries have used up fewer than 50% of doses received, according to the latest WHO data.

What caused early vaccine shortages?

The biggest problem facing the Covax scheme - which many African states were relying on - was its dependence on vaccines from the Serum Institute of Indi (SII) a, the world's biggest vaccine-maker.

India halted vaccine exports in April in response to its own urgent needs, and other manufacturers faced issues ramping up production.

These supply issues from India appear to be less of an issue now, with the SII announcing in early December that it was cutting back production because of a decline in new orders for its vaccines.

Wealthier countries had also signed deals with manufacturers for prospective vaccines as early as July 2020, while they were still in development and undergoing trials.

They were given priority by manufacturers - making it difficult for the Covax scheme, the African Union and individual countries to secure doses. In September, a Covax statement said it was reducing its estimate of the number of doses it expects to receive for the rest of this year and into 2022.

An update in December said that although Covax supply had increased, there was still uncertainty over the numbers of doses it might get., external

The WHO says Africa needs more than 900m vaccine doses to fully vaccinate 40% of its population.

As of 30 December, the continent had received just over 474m doses in total - from the Covax initiative as well as the Africa Union vaccine acquisition scheme, and through bilateral deals.