Covid lockdown: Why Magna Carta won’t exempt you from the rules

- Published

The owner of the Quinn Blakey hair salon has been fined thousands despite citing Magna Carta as a justification for opening

Business owners determined to escape coronavirus restrictions have resorted to citing obsolete and irrelevant laws.

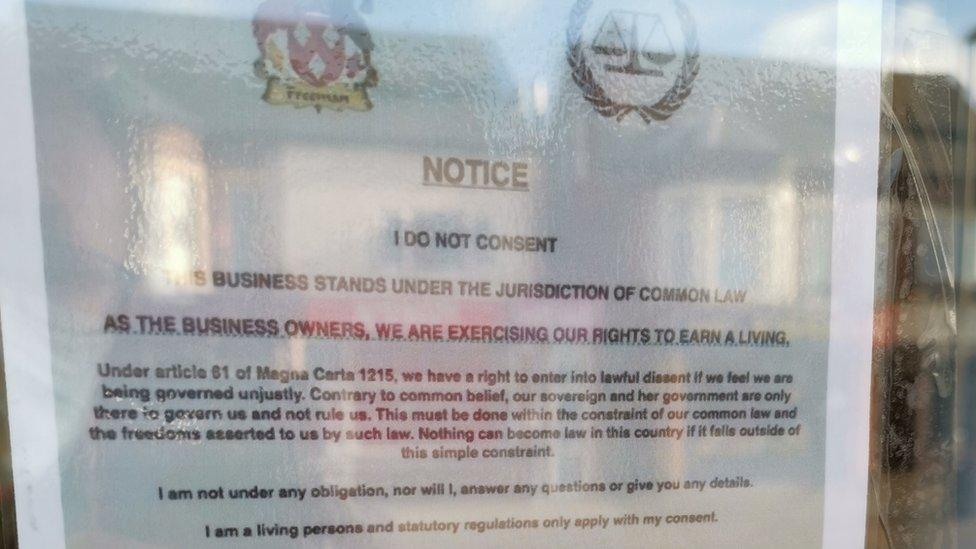

Sinead Quinn owns a hair salon in Oakenshaw near Bradford. She attempted to open the shop during lockdown, putting a sign in the window declaring that Article 61 of Magna Carta allowed her to opt out of the law and that she "does not consent".

She now owes nearly £20,000 in fines and costs, external after repeatedly trying to defy coronavirus laws.

Ms Quinn is one of a small number of business owners who have tried to use an obsolete clause in the 800-year-old charter of rights to insist on their freedom to reopen.

Such attempts are part of a larger "pseudolaw" movement - the use of non-existent or outdated legal arguments to defend a case - which goes back decades.

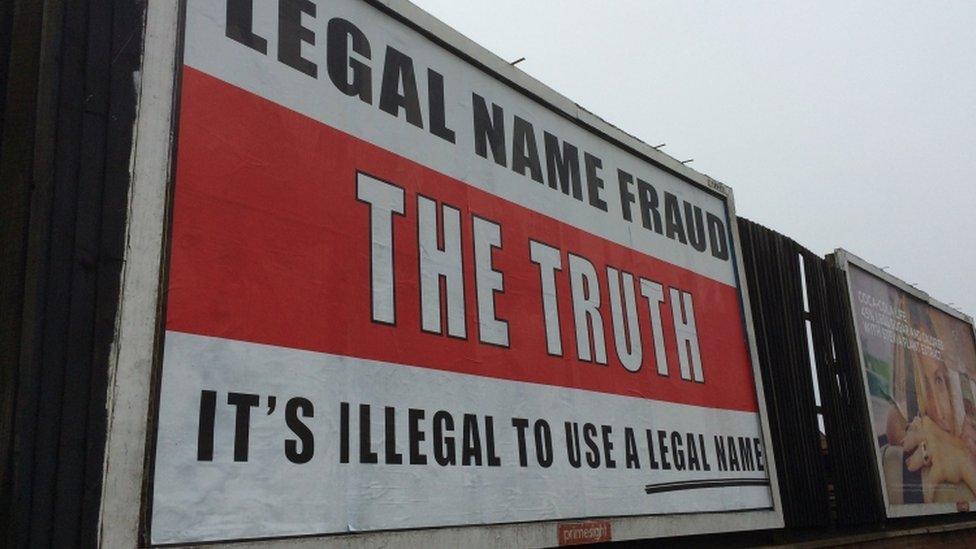

In addition to Article 61, this includes bizarre sounding and legally invalid concepts like "freeman on the land", "sovereign citizens" and "legal name fraud".

They're all based on invalid legal arguments - and on several occasions they've resulted in fines and other legal trouble for the people who attempt to use them.

Some might characterise such attempts as a wilful defiance of the law. But according to Ellie Cumbo, head of public law at the Law Society, such cases often arise from ignorance of the legal system, which is then made worse by poor advice found online.

Some businesses have used a misleading notice found on the internet to justify staying open

The hairdresser and Magna Carta

Ms Quinn has defended her actions, saying that she had a right to earn a living, gaining her support among fringe anti-lockdown campaigners. She has reportedly crowdfunded a five-figure sum to help pay her fines.

She's one of several businesses in the UK, including a tattoo parlour in Bristol and a Christian bookshop in Nottinghamshire, whose owners claim the medieval charter gives them the right to ignore "unjust" laws.

The same notice was posted in extreme anti-lockdown groups on social media, as part of a campaign that called for a "great reopening" of businesses in defiance of the law at the end of January, which largely failed to materialise.

The BBC has asked Ms Quinn for comment.

Much of Magna Carta, a copy of which can be seen here in Salisbury Cathedral, is no longer valid in law

Why Magna Carta?

Magna Carta, signed in 1215 by King John, was a royal charter of rights designed to bring peace between the King and his barons.

Although it is one of the foundational documents of English law, only four parts of Magna Carta remain valid today - including the right to a fair and timely trial.

None of those still-valid clauses allows citizens to decide which laws should apply to them.

The portion that the activists have been citing, Article 61, was struck from Magna Carta within a year of its signing, and only applied to a small group of barons in the first place, external, according to fact-checking website Full Fact.

However, belief in Article 61 remains strong in extreme right-wing and anti-establishment circles. Despite the fact that it has no legal standing, it's held up as "the one true law" and seen as justification for rebellion against legal and political "elites".

Ellie Cumbo of the Law Society says that the embrace of "alternative" legal concepts has parallels with the rejection in some quarters of so-called "elitist" scientific expertise across society, which has accelerated during the pandemic.

"Some think they can opt out of law in the same way that some people think they can opt out of science and vaccines," she says.

Billboards warning of 'legal name fraud' appeared in 2016

Sovereign citizens versus the law

Beyond Article 61, people are using other "pseudolaws" to try and fight prosecutions unconnected to Covid legislation.

In recent months, there have been cases in English and Scottish courts where baseless legal concepts have been raised to avoid planning enforcement and driving offences.

In January, a man said he did not consent to a ruling by Stockton Council's planning department that he should remove a balcony from his home, on the grounds that he was a so-called "Freeman on the Land", external and did not recognise legal entities such as courts and local councils.

Similarly, a man in Fife told the Kirkcaldy Sheriff Court in February that he did not recognise its authority, saying - according to Dundee's Courier newspaper, external: "I am a living man, the blood flows, the flesh moves - I wish for remedy".

In both cases, their arguments did not prevail. In fact, no defence based on so-called freeman on the land, sovereign citizen or legal name fraud theory has ever succeeded in court.

These theories aren't new either. Sovereign citizen theory - which maintains that the individual is independent of the state and can ignore its laws - has been around for decades, and is seen as a domestic terrorism threat by the FBI in the United States, external.

Little of the original Magna Carta remains in law, but the document still forms an important part of the British legal system

Google results vs actual law

A lack of basic legal knowledge means that people get the wrong idea about how law works, according to Ms Cumbo.

"We rightly celebrate Magna Carta as an important part of our legal system, so it's understandable that people think that the full original text still has full legal standing," she says.

But there is a difference, she notes, between people who deliberately take a stand against laws passed by elites which they think are unfair or not particularly clear and those who have been swept along by bad legal advice from inaccurate sources found online.

A final piece of advice for those wanting to use Magna Carta as the go-to law to fight any grievance?

"Go to a lawyer, not Google," Ms Cumbo says.