India Covid crisis: Did election rallies help spread virus?

- Published

India is reeling from a record rise in Covid-19 cases, with the health system struggling to cope.

Despite the surge in cases and moves to restrict election-related activities, campaign rallies and voting in some states have continued.

The ruling party in India, the BJP, has rejected the idea of a link to the rise in infections.

"High cases have nothing to do with religious or political gatherings," Dr Vijay Chauthaiwale, of the BJP, told the BBC.

What's happened to case numbers?

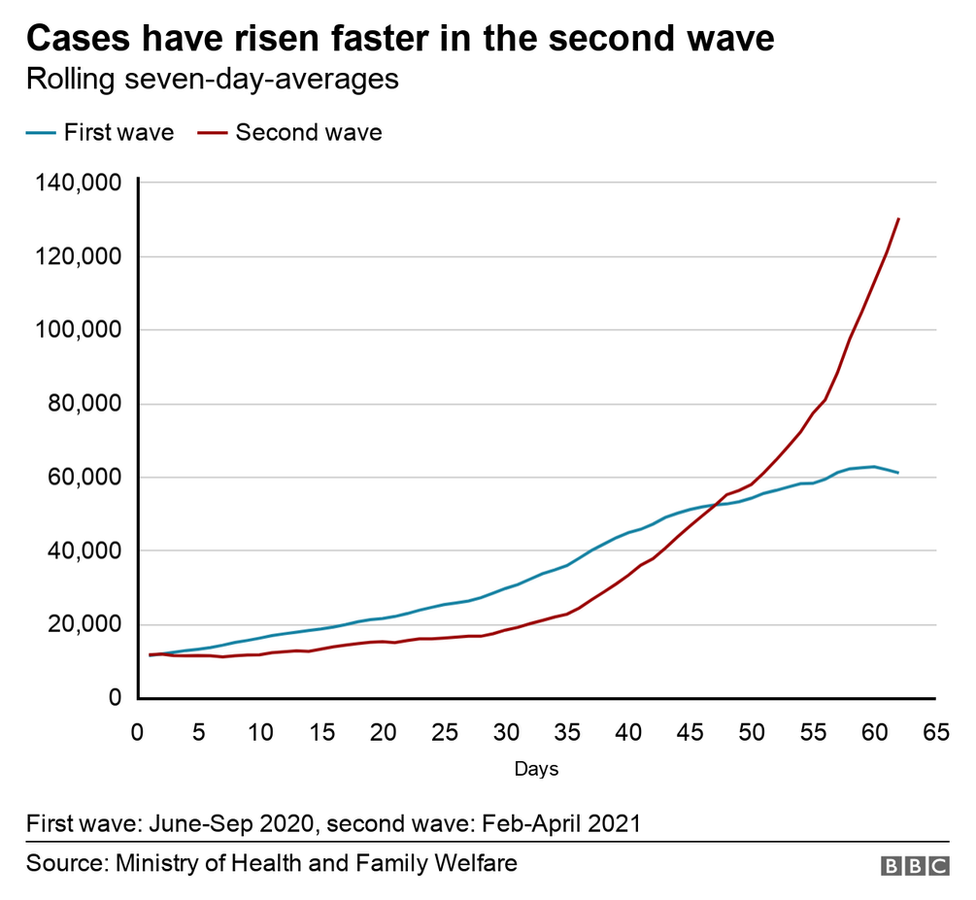

India's daily case numbers began rising at the end of February after falling steadily from mid-September 2020.

They picked up sharply in March, and reached record highs this month, and you can see that the rate of growth has outpaced the rate seen in the first wave which hit India in 2020.

At the same time, India's political parties have been campaigning for a series of state elections in West Bengal, Assam, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, as well as local council elections in some parts of Uttar Pradesh and Telangana states.

This has been going on since early March, with voting starting at the end of March, and carrying on through April.

Was there a spike due to election rallies?

The campaigns have often involved numerous rallies with large crowds - with minimal social distancing and very little mask-wearing.

Political campaigners and candidates were also seen not following Covid safety protocols.

India's election commission had issued warnings about such gatherings in one of the key election battlegrounds, West Bengal state - although they don't appear to have been heeded.

On 22 April, restrictions were placed on big public events, limiting political meetings to 500 people as long as they could be held in accordance with Covid safety rules.

In Tamil Nadu state, the commission was publicly rebuked by a court for not taking action earlier to stop big public rallies there.

"Your institution is singularly responsible for the second wave of Covid-19," the Madras high court said.

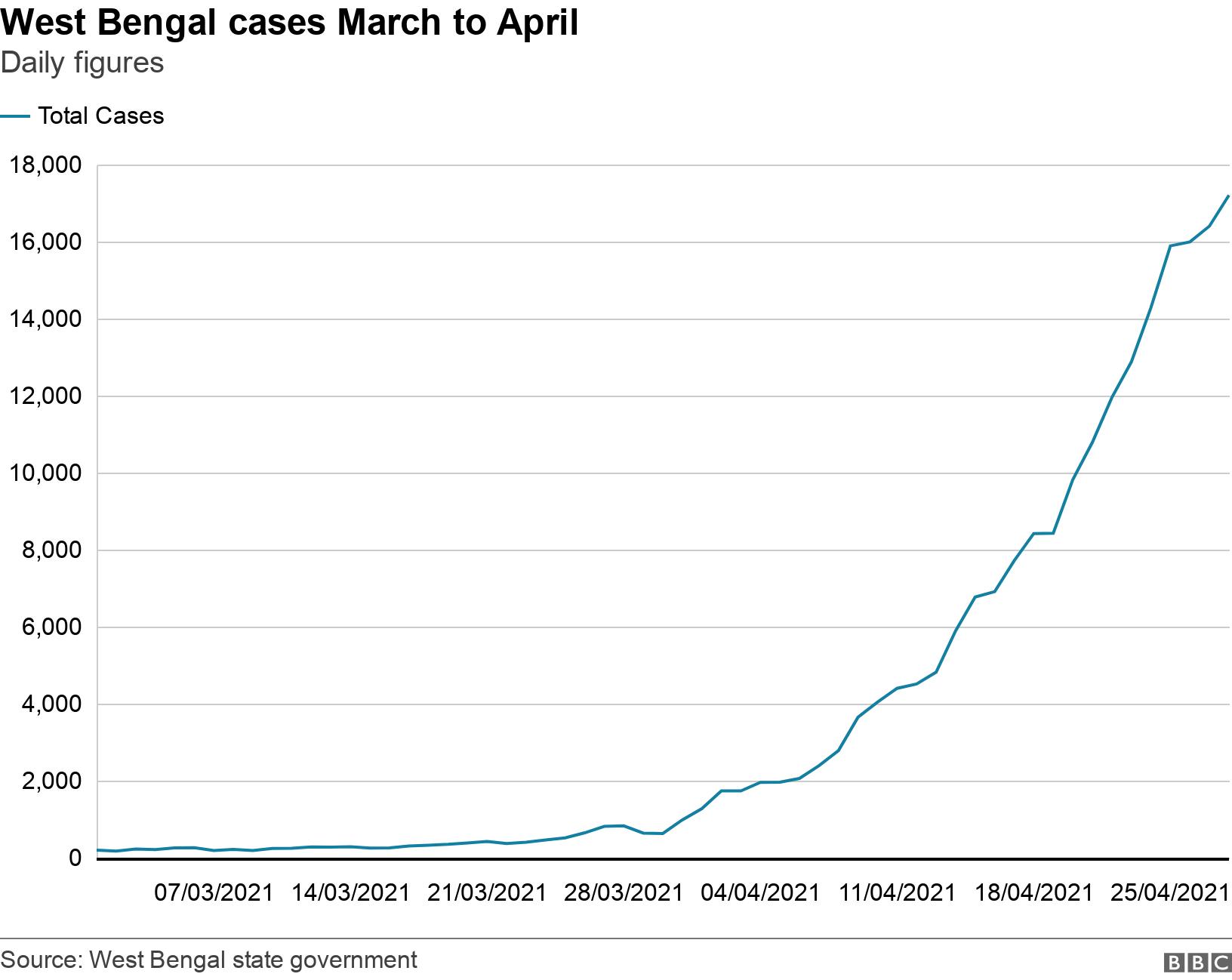

In West Bengal, there's a clear upward trend in daily coronavirus cases starting in the second part of March and then very sharp increases afterwards.

And in other election states there were similar big increases in late March or early April as well - in Assam, Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

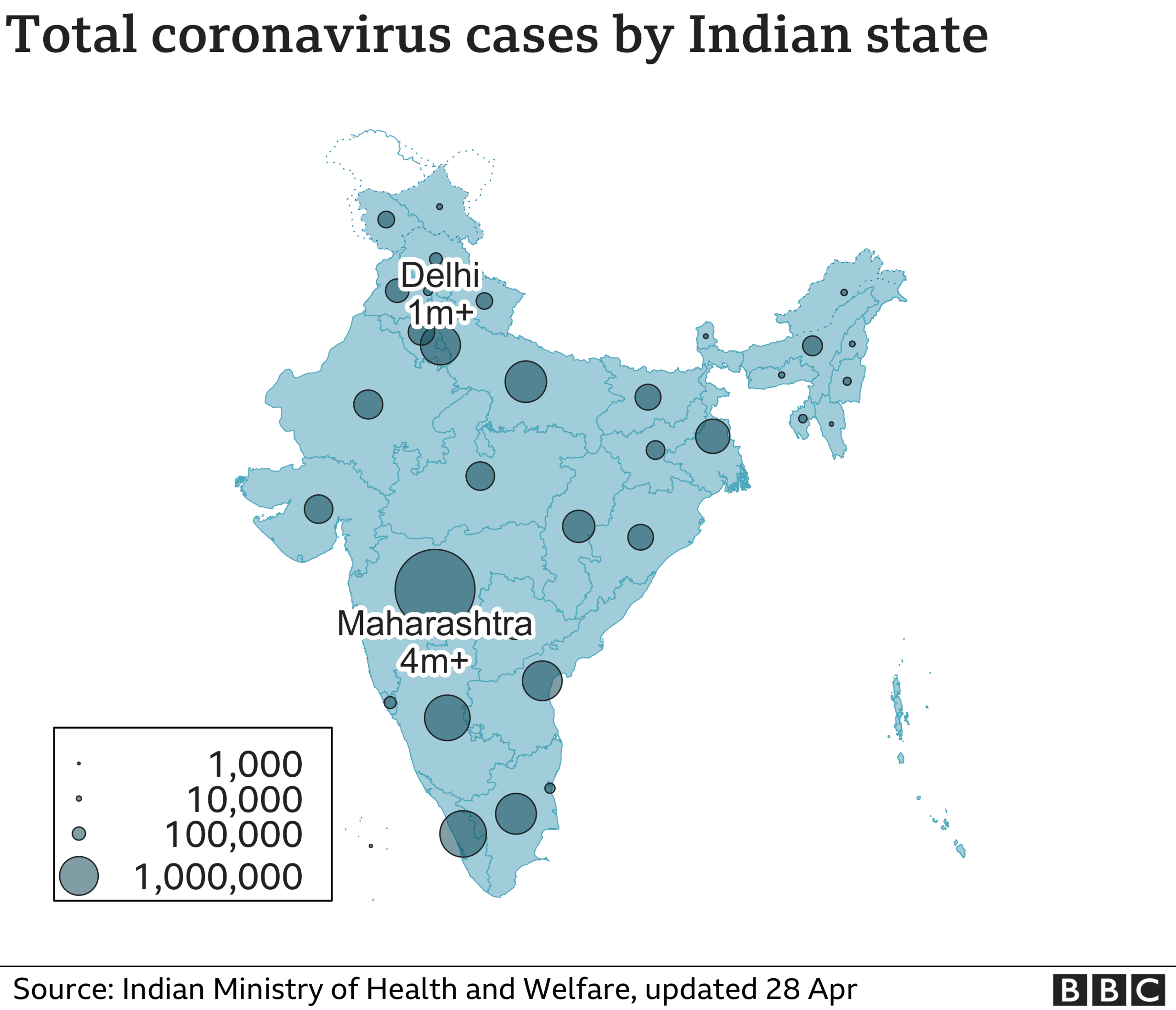

But this timeframe for surges in case numbers is by no means unique to these four states, and is found in other parts of India as well.

For example, there are big case numbers with significant spikes over short periods of time in Maharashtra and Karnataka, neither of which have held election campaigns.

Also, we don't have local-level data for infection rates among people living in the places where the biggest rallies were held (and who were most likely to have attended them) to establish clearly if these could have spread the virus significantly.

What's the risk at outdoor events?

The risk of virus transmission at outdoor gatherings is generally very low compared with events held indoors, say experts.

"Not least [is] the fact that the virus released can be rapidly diluted through the atmosphere," says Prof Lawrence Young of Warwick Medical School.

A crowd - mainly without masks - at a BJP rally in West Bengal state

But there are some factors that could increase the chance of transmission at events such as political rallies.

If people are in crowded places, in close proximity to others for long periods of time, not socially distanced and without good ventilation, then infections are possible.

"There are bound to be pockets of people in confined spaces outside in close proximity to people excreting the virus. [It's a] distinct possibility that could lead to infections," says Prof Young.

Prof Jonathan Reid at the University of Bristol says that despite factors that substantially reduce the risk of transmission outside, standing in close proximity will still lead to a significant risk, particularly within 1m downwind of someone and face-to-face.

"This will be particularly significant if the individual is generating an increased number of droplets and aerosols by shouting loudly."

Could a new variant be behind the surge?

Scientists are investigating whether the new variant of coronavirus that first emerged in India last year might be responsible for the country's second wave.

Crowds at India's Kumbh Mela amid Covid wave

Experts say it is possible, but there is still not enough evidence to determine any causal relationship.

Due to a lack of data, the Indian variant is not currently listed by Public Health England as a "variant of concern" - a term used to describe the UK, Brazilian and South African variants.

It's worth noting that there's been a major religious festival in northern India as well since early March.

The Kumbh Mela attracts millions of devotees from all over the country, and there's been little sign of safety measures at it.

More than 1,600 positive cases were detected at this event between 10 and 14 April.