Are Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak right about wages rising?

- Published

BBC's Andrew Marr challenged Boris Johnson's claim that wages are rising for the lower paid.

There has been much talk from the government in recent days about rising wages. But what's actually happening?

Boris Johnson: 'Wages are growing'

The prime minister argued with Andrew Marr on Sunday about what has happened to average wages.

The prime minister said we're finally seeing "growth in wages, after more than 10 years of flat-lining" but Andrew Marr said that "in real terms over the last three months wages have gone down, not up".

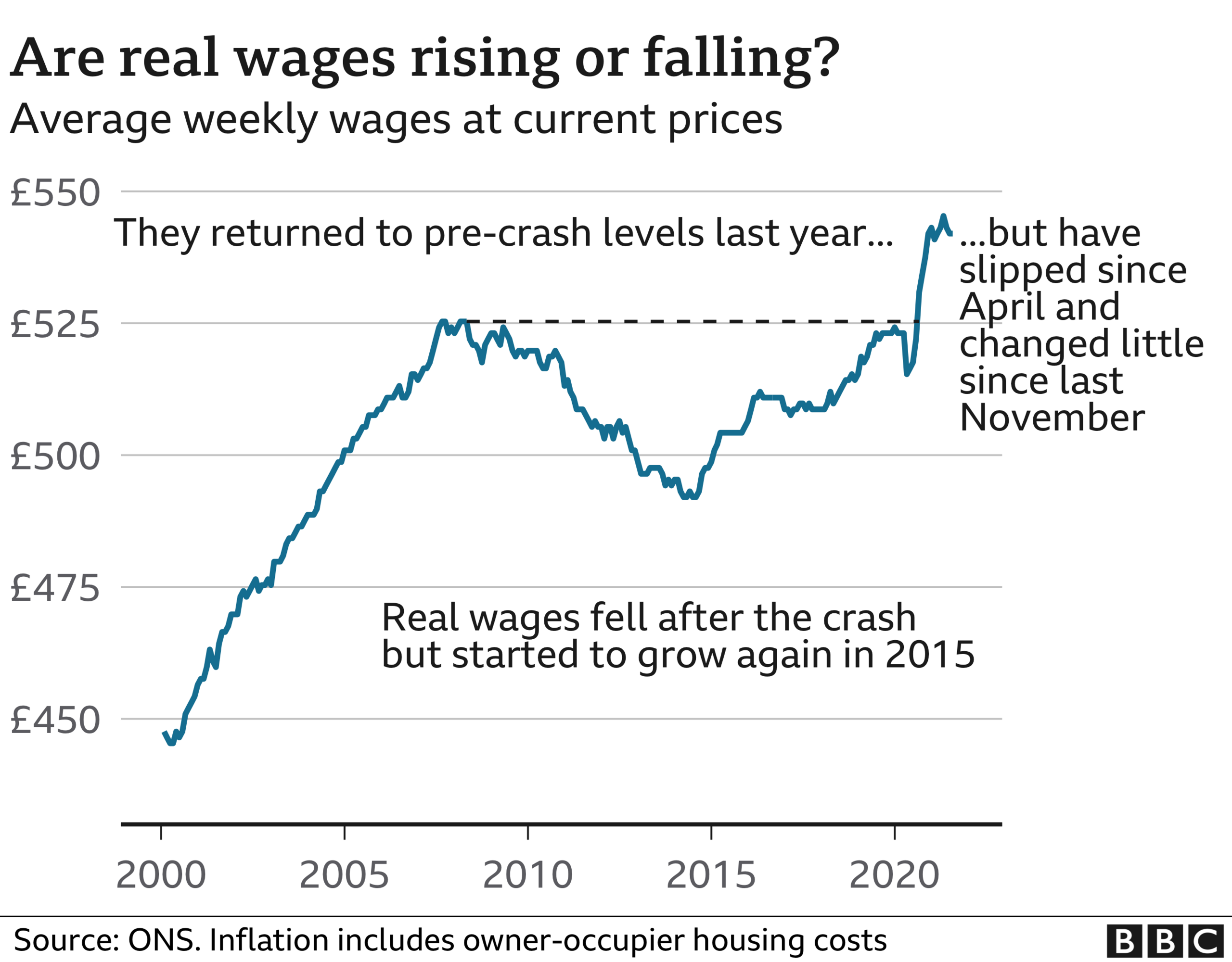

Real wages is a measure that takes account of rising prices, so it reflects what the money you earn actually buys. They peaked just before the financial crash in 2008 and only returned to that level in August 2020.

So, there has been a decade of little improvement overall.

Rather than "flatlining" - as Mr Johnson claimed - it was actually roughly five years of falls followed by growth over most of the past five years.

Last year saw record dips and jumps as the economy was shut down and then re-opened.

But the most recent figures, external from the Office for National Statistics suggested that growth might be stalling, with real wages looking lower in July than they were in April.

And that is likely to get worse, with a jump in inflation (rising prices) already reported for August, external as well as rising energy prices.

Rishi Sunak: 'Wages are rising and that is a good thing - that's a positive thing - we want to see that'

The chancellor and the prime minister have been talking a great deal about rising wages in the run-up to their party conference.

But there is a lot going on in the labour market at the moment, which makes it difficult to work out exactly what the real trends are.

The government decided to suspend the pensions triple lock this year because of those problems.

The triple lock is a promise that pensions will rise by the highest of average earnings, inflation or 2.5%.

But this year, average earnings will be ignored, preventing a big increase in the state pension.

Work and Pensions Secretary Therese Coffey said the figures had been "skewed and distorted" and described the average earnings rise as a "statistical anomaly".

People coming on and off furlough in the past 18 months have certainly made the average earnings figures harder to interpret.

The ONS points to, external two temporary effects.

Average earnings fell in the first months of the pandemic as people were furloughed, which meant in many cases their pay fell, or they worked fewer hours. The annual figures we are now seeing are compared with early in the pandemic, which is making the increase in wages bigger.

Also, throughout the pandemic, more low-paid employees have lost their jobs than high-paid employees, which means that average earnings have gone up.

Rishi Sunak: 'Thankfully we're seeing that [wage rises], particularly for those on lower incomes'

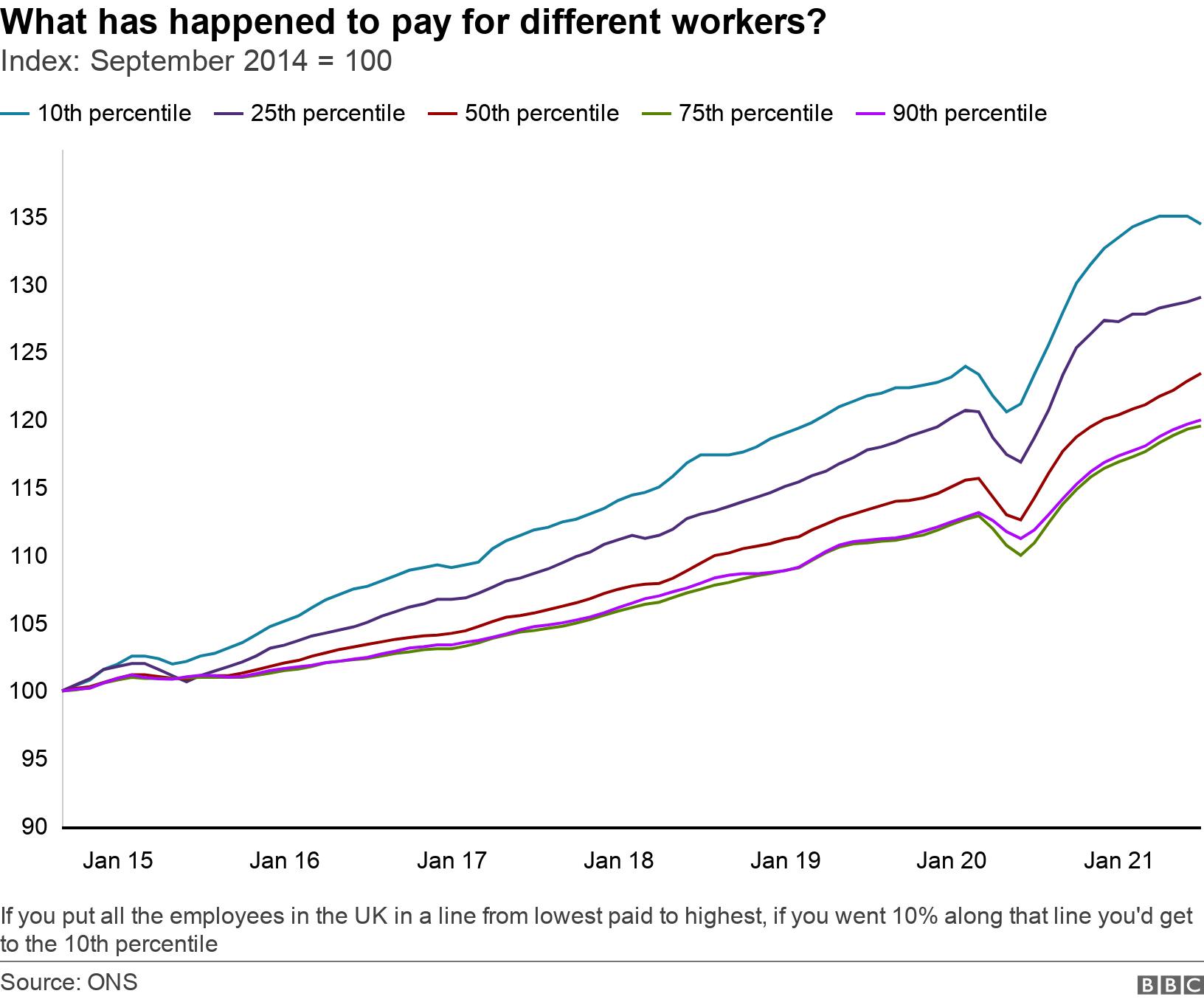

The ONS has recently started publishing monthly pay figures, external for employees broken down by their earnings levels.

If you imagine putting all the employees in a line from lowest earning to highest, the 10th percentile would be 10% along the line and the 50th percentile would be half way along the line.

It is clear that since 2014, there has been higher percentage growth in earnings at the lower end of the scale than at the top, although it has flattened recently.

The higher-paid have had bigger increases in terms of pounds and pence.

The ONS warns that the recent figures on the chart above need to be treated with caution for the same reasons as the overall earnings figures.

There are a few things going on that may explain why the rise for the lower-paid has been happening.

Firstly, we know that the National Living Wage has been rising faster than earnings overall in recent years, so lower-paid workers have been seeing their pay rise more than average.

Secondly, during the pandemic, people on lower incomes were more likely to be furloughed, and coming off furlough and back into work would mean an increase in pay for many people.

Thirdly, some of the sectors that have seen shortages of workers such as hospitality and delivery drivers are likely to employ lower-paid workers, who may benefit from pay rises.

But of course wages figures do not take into account benefits, and one thing that will be hitting many of the lowest-paid workers is the ending of the £20 a week boost to Universal Credit. About 40% of Universal Credit claimants are in work, external.

Also, just because average earnings are rising, it does not mean everybody is being paid more.

For example, there are 2.6 million workers, according to the Resolution Foundation, affected by the public sector pay freeze, who will also not benefit from rising wages.

And rising prices will make it feel as if they have effectively had a pay cut.