North Korea: The mystery of its Covid outbreak

- Published

North Korean poster asks: "Comrade, are you keeping to the emergency virus prevention rules?"

It's been three weeks since North Korea announced its first ever Covid case. The government claims to have the outbreak under control, but the details remain a mystery.

The BBC has pieced together information, through conversations with people who have managed to contact those living in North Korea, and by using publicly available resources.

Voices inside North Korea

Kim Hwang-sun was sitting alone in his kitchen in Seoul when his phone rang. It was a Chinese broker with the news he'd been waiting for. His family could talk.

It has been 10 years since Hwang-sun escaped North Korea alone. His two children, grandchildren and his 85-year-old mother are all still there, and he's given up hope of ever getting them out.

These secret phone calls are the only communication he has with them. He knows not to ask too much in case they're being listened to. He keeps his conversations short, never more than five minutes.

Two days earlier, North Korea had announced its first coronavirus case.

Data released by the government, in an unprecedented move, indicates the virus spread quickly to every province in the country.

"They told me that very many people are sick with a fever," says Hwang-sun. "I got the sense it was really bad. They said everyone is walking around asking anyone they meet for medicine. Everyone is looking for something to reduce their fever, but no-one can find anything."

He didn't dare ask how many people were dying. If they were overheard talking about deaths, it could be seen as criticising the government, and he fears his family might be killed.

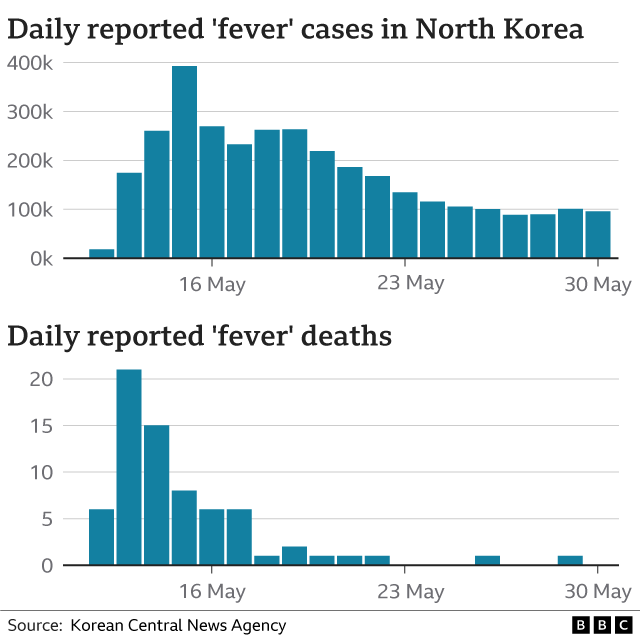

So far, about 15% of the population has become ill with a "fever" according to the official data. A lack of testing means this is how cases are described.

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un has acknowledged the shortage of medicine, ordering the army to distribute their stockpiles.

The army has been mobilised to distribute its stockpile of medicines in pictures shown on North Korean TV

Hospitals and pharmacies in North Korea haven't had any medicine for years, says Hwang-sun. Doctors write a prescription, and it is up to the patient to find what they need and buy it, either from someone selling directly from their house, or from a local market.

"If you need anaesthetic for an operation, you have to go to the market to get it and bring it back to the hospital," he says. "But now even the market-sellers don't have anything".

"The government is telling us to boil pine leaves and drink the mixture instead," his family told him. State news reports have also advised gargling salt water to relieve symptoms.

North Korean state TV has broadcast images of well-stocked pharmacies, but people have spoken of an acute lack of medicine

"This is what happens when they have no medicine. They shift to traditional medicine," says Dr Nagi Shafik, who has worked for Unicef in North Korea's villages since 2001. When he was last there, in 2019, medicine was already short. "There was some, but very, very little," he says.

Almost all medicine is imported from China and the last two years of border closures have choked off this supply.

Sokeel Park, from the organisation Liberty in North Korea, helps escapees from the North settle in the South. Those who have spoken to family back home have told him there has been a run on medicine. "What little was left has been bought up, pushing prices sky-high," he says.

A national lockdown

The government ordered a national lockdown on the day the outbreak was announced. It prompted concern that people, unable to get food, would starve. At least some, however, appear to have been able to leave their homes to work and to farm.

Photo taken on 16 May appears to show North Koreans out planting rice in the North Hwanghae Province

Pictures taken across the border in South Korea by the monitoring website NK News show agricultural workers in the fields in the days after the lockdown was imposed.

However, in places with high rates of infection, including the capital Pyongyang, people are reported to have been confined to their homes.

Empty street scene in Pyongyang on 23 May

Lee Sang-yong runs the Daily NK, a Seoul-based website, and has a network of sources inside North Korea. In the town of Hyesan on the Chinese border, he says people were not allowed to leave their homes for 10 days in May. When the lockdown was lifted, according to his source, more than a dozen people were found collapsed in their homes, weakened from a lack of food.

So far, just 70 deaths have been officially reported. This would put North Korea's Covid fatality rate at 0.002% - the lowest in the world.

"For a country with a poor healthcare system, where no-one is vaccinated, these numbers don't make sense," says Martyn Williams, who has been tracking the data for the analysis platform 38 North.

He points out another oddity. Deaths peaked while cases were still rising. "We know with Covid-19 that deaths tend to follow infections by two to three weeks. So, we know these figures are incorrect, but we don't know why."

He explains that as well as misreporting at a national level, local health officials may not want to admit how many people have died, for fear of being punished.

International help

Over the past week, the number of reported new cases has dropped, with an editorial in the country's state newspaper claiming the authorities have "suppressed and controlled the spread of the virus".

Unicef says that their local staff have now returned to their Pyongyang office after being released from lockdown.

In a briefing by the World Health Organization on Wednesday, emergency health official Dr Mike Ryan said he feared the situation was "getting worse, not better". He said North Korea had not given them access to its data, making it "very difficult to provide a proper analysis to the world". He also said they had offered multiple times to send vaccines and assistance.

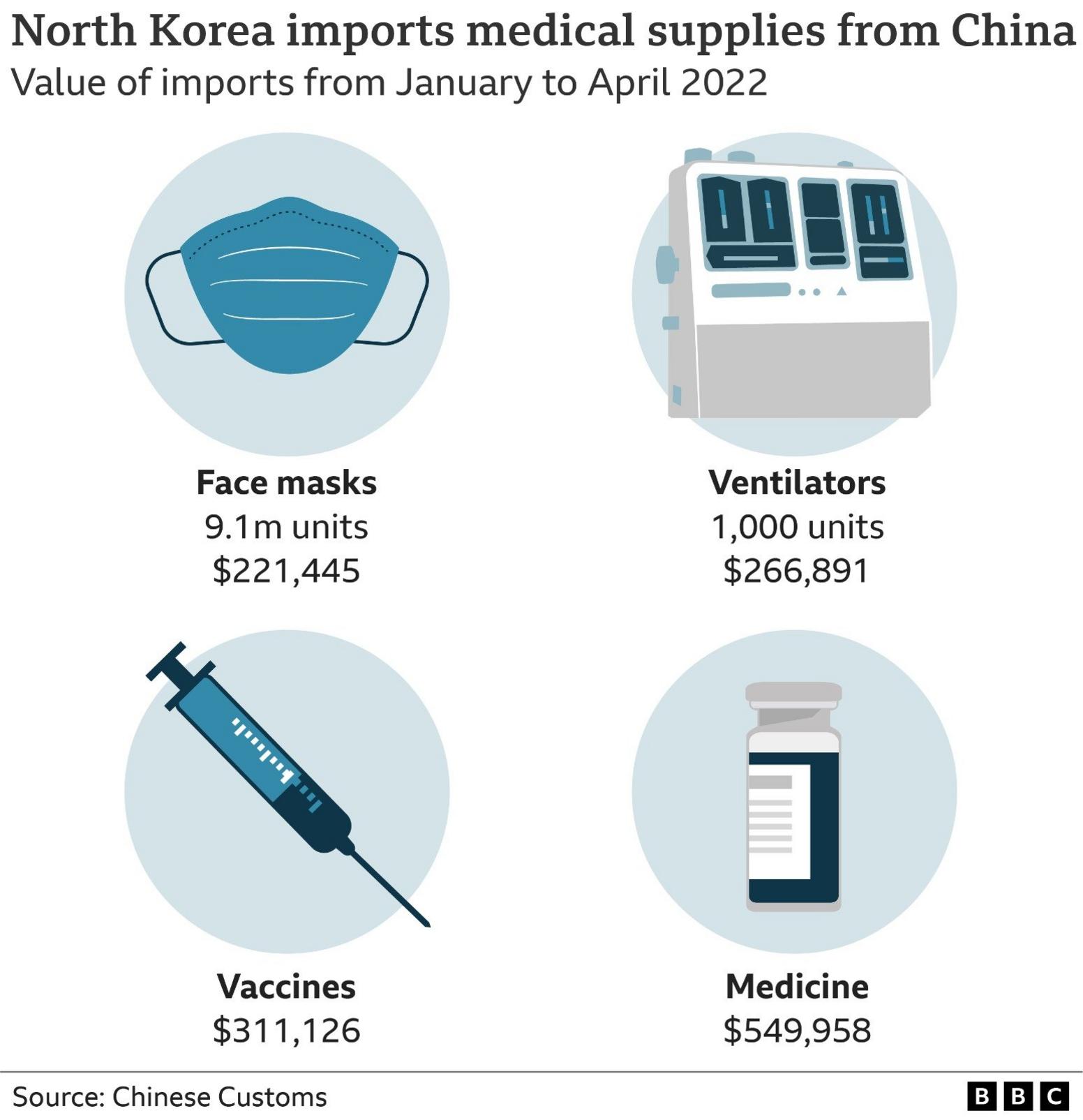

Instead, North Korea appears to be quietly relying on its neighbour China to pull it through.

Chinese customs data shows that North Korean imports from China doubled from March to April.

Although imports have been steadily increasing this year after a two-year border closure, in the last few months there has been a sudden increase in imported medical supplies.

In April, North Korea imported 1,000 'ventilators' from China - the first batch since the pandemic began, according to Chinese customs data.

The term 'ventilator' in the Chinese data may also refer to other, smaller types of oxygen treatment machines.

From January to April, North Korea also bought more than nine million face masks. None were registered in the Chinese customs data over the previous two years. There's also been an increase in medicines and vaccines imported.

According to a South Korean government official, the North sent three cargo planes to China to pick up aid on 17 May.

Satellite images from 24 May show three Air Koryo (the state-owned national airline of North Korea) cargo planes at Pyongyang airport which match the dimensions of three planes seen at the Shenyang airport in China a few days earlier, external.

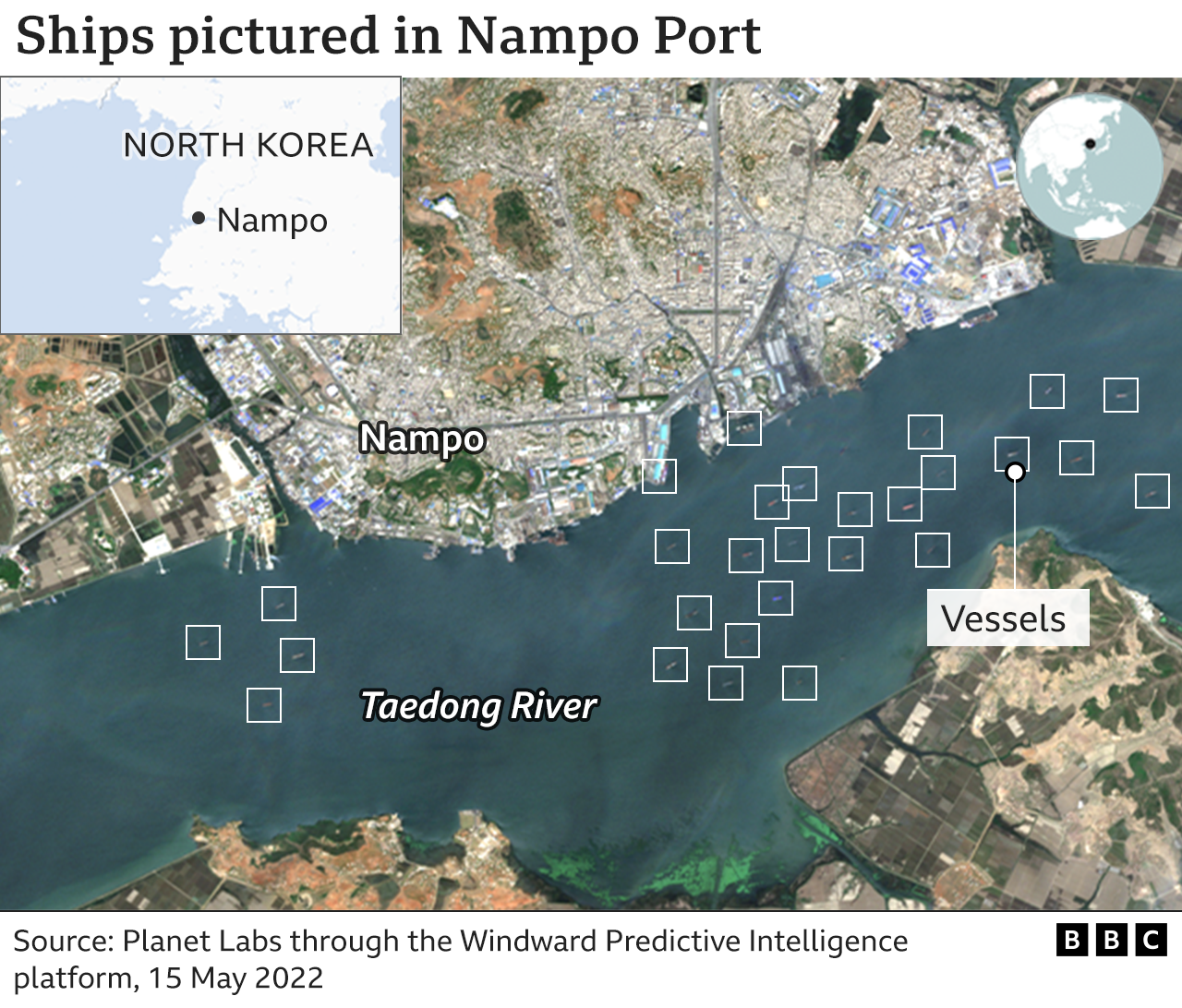

Separately, a source we spoke to said a large shipment of medical supplies had arrived by sea at Nampo port, south of Pyongyang, on 13 May.

We've obtained satellite imagery for 15 May. It reveals the presence of a large number of ships in the port area. Identifying where they came from and what they were carrying has, however, not been possible - as many of them have had their navigation trackers switched off.

Kim Hwang-sun hasn't heard anything from his family in the North since that first phone call.

Since the outbreak, he says it has become much harder to reach them. The phone signals are frequently jammed and when he does occasionally get through, he often gets cut off. His friends are experiencing the same thing.

He's so wracked with worry about what might have happened to his 85-year-old mother in the days since they spoke, that yesterday he climbed to the top of his local mountain and prayed for her. This is all he can do. Like the rest of the world, he is in the dark and unable to help.

Follow the BBC's Seoul correspondent Jean Mackenzie on Twitter @jeanmackenzie

Names have been changed to protect sources