Brazil election: Accusations and misinformation on the campaign trail

- Published

Claims about corruption, Covid, deforestation, and even cannibalism grabbed attention in the build-up to Brazil's presidential election.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva defeated current President Jair Bolsonaro in a second-round run-off on Sunday, and will take office on 1 January.

During the campaign, we looked at some of the main lines of attack for both candidates.

Satanism and cannibalism smears

Bolsonaro and Lula, who are both Catholic, sought support among evangelical Christian voters, who make up almost a third of Brazil's population.

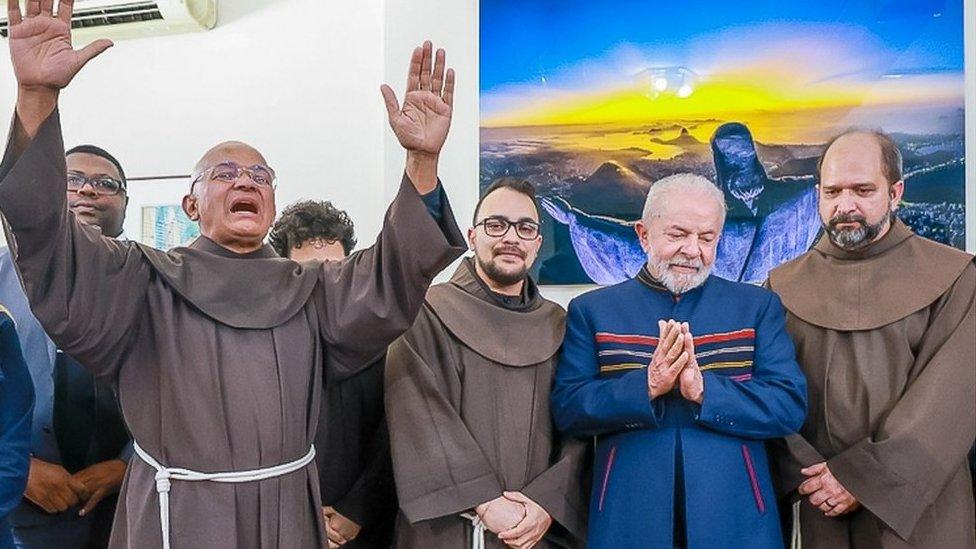

President Bolsonaro and his wife praying with evangelical leaders during the campaign

However, their strategies were rife with religious disinformation.

One example of this is a video shared by two of Bolsonaro's sons and other politicians, in which a social influencer who describes himself as Satanist, declares his support for Lula.

The video went viral, alongside messages saying that Brazil would be running a "spiritual risk" if Lula was elected - despite the influencer having no relationship with the former president nor any influence on his policies.

Lula's campaign team released a statement rejecting any involvement with devil worship and the video was banned by the Electoral Court, the body overseeing the vote.

Lula at an event with Franciscan friars in São Paulo during the campaign

Meanwhile, Lula's campaign team highlighted a 2016 New York Times interview, external with Bolsonaro in which he says he visited an indigenous community in Brazil that was allegedly cooking a dead person, and that he had asked to watch.

To see it, he recalls in the interview, he was told he'd have to join in the meal. "I would eat it," he said. "I'd have no problems in eating the indigenous person." But he added that his entourage did not want to go, and so he didn't, either.

Lula's campaign produced a video featuring the 2016 interview, saying: "It's monstrous. Bolsonaro reveals that he would eat human flesh."

Bolsonaro complained to the Electoral Court, which then banned Lula's campaign video, saying that it had portrayed the interview out of context.

Leaders of the Yanomami people, the indigenous group Bolsonaro was referencing, reject his claim and say that they do not practise cannibalism.

Protecting the Amazon rainforest

The rainforest plays a vital role in absorbing harmful carbon dioxide that would otherwise escape into the atmosphere, and about 60% of the Amazon is in Brazil.

Both Bolsonaro and Lula claim to have a better record at protecting it.

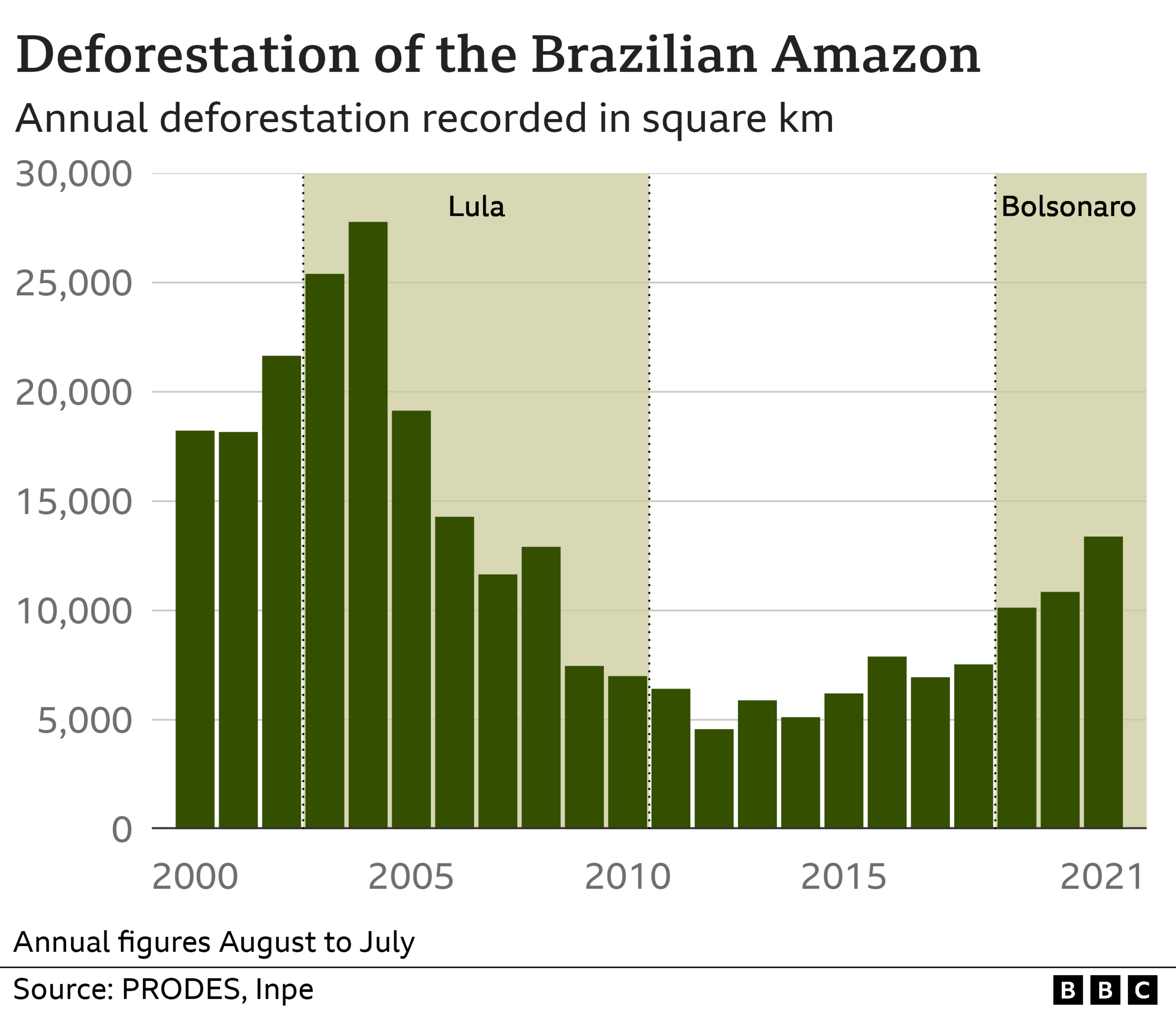

During a live presidential debate in October, Lula said: "In our government, [we had] the lowest deforestation in the Amazon, and in yours it is the highest every year."

Deforestation rate in the Amazon has increased in recent years

Bolsonaro replied: "Google 'deforestation from 2003 to 2006', in the four years of Lula's government. Then search for 'deforestation from 2019 to 2022'.

"During your government, twice as much was deforested as in mine," he added.

It's true the amount of deforestation during the first three years of Bolsonaro's government is significantly less than in the same period under Lula - about 34,000km squared, compared with 71,000km, according the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe)., external

But after Lula's first two years in office, the rate of deforestation dropped significantly, and by the time he left office in January 2011, it had reached historic lows.

Under Bolsonaro, the rate of deforestation has gone up each year, continuing a trend that began a couple of years before he took office in January 2019.

He has implemented policies that critics say roll back crucial safeguards, and prosecutions against illegal logging have dropped during his time in office.

Corruption allegations

Corruption was a central theme in the campaign.

Bolsonaro highlighted a major corruption scandal, which began during Lula's previous period as president, when billions of dollars were stolen in bribes and overpriced oil contracts linked to the state-run oil company, Petrobras.

Lula himself was found guilty of involvement and in 2017 he was sent to prison. His conviction was annulled last year, enabling him to stand in this election.

For his part, Lula pointed the finger at Bolsonaro for enabling corruption, and accusing him of losing control of the country's finances. By this he's referring to a "secret budget" included in the budget law passed in 2019, allowing for public funds to be spent by federal lawmakers with limited oversight.

Congress now controls large sums of public money through non-transparent amendments

Bolsonaro denies having approved the scheme. "I vetoed it and [Congress] overrode the veto," he said during a debate on October 16.

That's not true. At first, in November 2019, Bolsonaro did veto the new mechanism included in the budget. One month later, however, the presidency itself sent Congress a new proposed bill, including the "secret" mechanism within it, and it was approved.

"It's an institutionalisation of corruption, a way of buying Congress using the country's budget," says Bruno Brandão, executive director of the Brazilian national chapter of Transparency International.

He points out that press and police investigations have shown there are widespread fraud schemes involved in the application of these public funds.

Tackling Covid

Bolsonaro has been accused of spreading misinformation about Covid vaccines, and has refused to get the jab himself.

Lula has heavily criticised Bolsonaro's efforts to control the pandemic.

During the campaign, he highlighted the country's death toll, saying: "Brazil has 3% of the world population, and Brazil has had 11% of deaths from the pandemic in the world."

It's correct that Brazil has accounted for almost 11% of the world's official Covid deaths, with more than 687,000 recorded, according to Johns Hopkins University., external

That's the second-highest official death toll in the world after the United States.

It also has one of the highest recorded global death tolls as a proportion of its population - although not as high as neighbouring Peru.

But official figures may not fully reflect the true number of dead in many countries, as testing is not always available.

Lula also questioned the amount of time it took to roll out Covid vaccines.

Defending his government's record, President Bolsonaro said: "We have purchased over 500 million doses of vaccine… and Brazil is one of the most vaccinated countries in the world and in the fastest time."

President Bolsonaro continued to hold rallies with supporters throughout the pandemic

Bolsonaro's government has now purchased about 750 million doses, external, but its first orders went in much later than those of some other countries.

This meant vaccine delivery was delayed, and Brazil's rollout initially lagged behind many other countries in Latin America and around the world.

Brazil has now administered more than 220 doses per 100 people, external, but this is still below the levels of several other countries in the region, including Argentina, Chile and Peru.

Graphics produced by Sarah Habershon.