Has the Brexit fishing promise come true?

- Published

Even though fishing is a tiny part of the UK economy, it was a key issue in the Brexit campaign with promises to "take back control" of British waters.

At the end of 2020, Boris Johnson announced his new Brexit trade agreement with the EU, promising that "[we will] be able to catch and eat quite prodigious quantities of extra fish".

What are the new fishing rules?

The UK-EU fishing rules, which came into force at the start of 2021, mean:

New quotas for about 100 fish species caught in UK waters

UK boats get bigger share of about 60 of these

25% of EU's overall share transferred to UK between 2021-2026

EU boats get access to UK waters until 2026

There was give and take because UK boats still needed to sell their fish to EU markets.

The UK now negotiates annually with non-EU fishing nations such as Norway and the Faroe Islands. Before Brexit, it was covered by the EU's negotiations with them.

Is the UK catching more fish?

Government figures show the amount of fish UK boats caught and landed in the UK (and at ports in Europe) has been rising:

2019 - 622,000 tonnes

2020 - 623,000 tonnes

2021 - 652,000 tonnes

Mark Spencer, the fisheries minister told MPs in December 2022: "We are 30,000 tonnes better off now that we are outside the EU".

Dr Bryce Stewart, a fisheries biologist from the University of York, believes the government has overstated the longer term impact, external.

He says most of the benefit came in 2021, because 15% of the EU's quota was transferred then, external, with much smaller transfers to come up to 2026.

He also points out: "Quotas are not always fished to their full extent. Fish are unpredictable, they might not always be where you think they are, the weather might be too bad to fish and markets might not be available."

Winners and losers

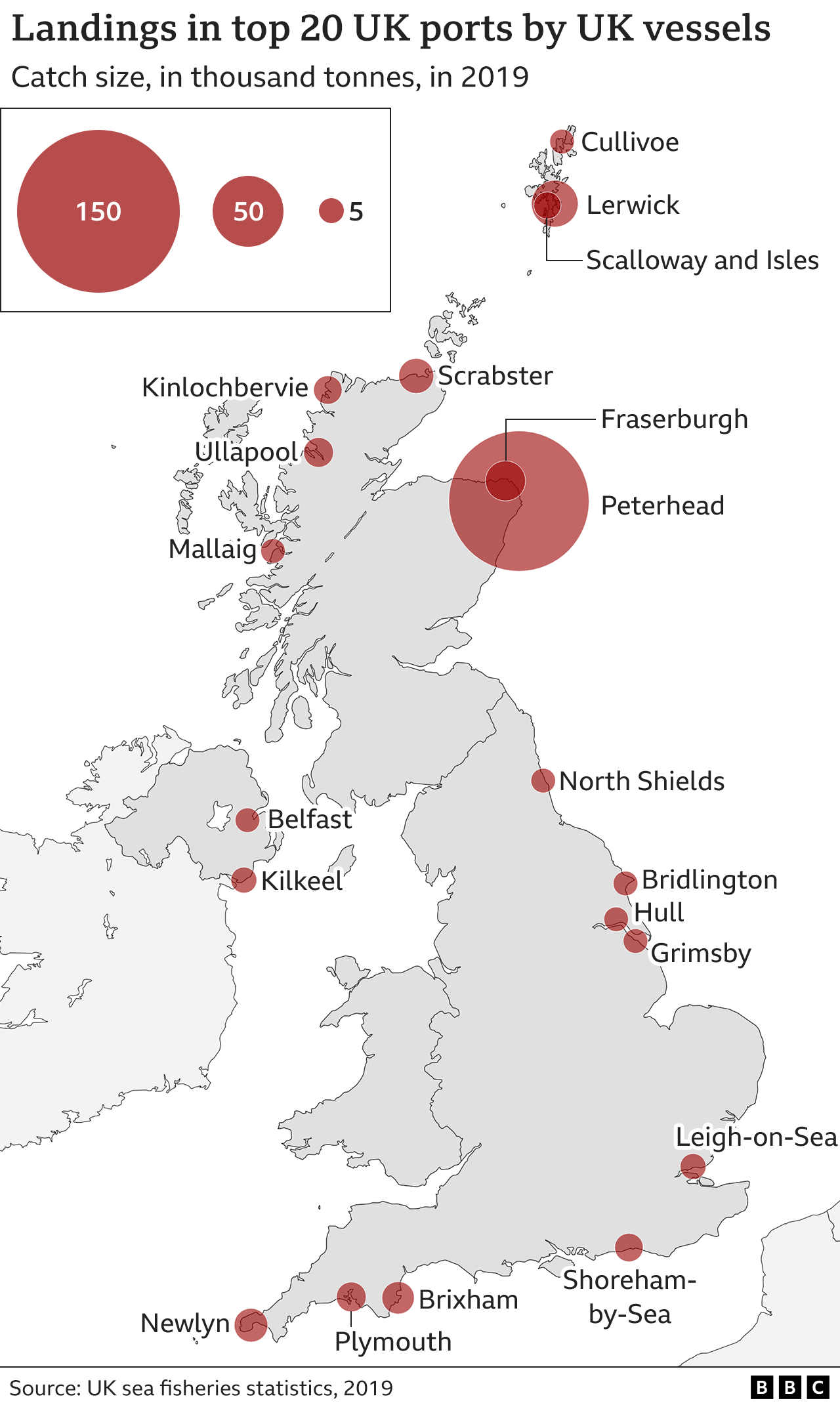

In 2019, the top UK port for the amount of fish landed was Peterhead in north-east Scotland, with 132,000 tonnes, followed by Lerwick, on the Shetland Islands, with 28,000 tonnes.

They accounted for more than a quarter of all landings by UK boats.

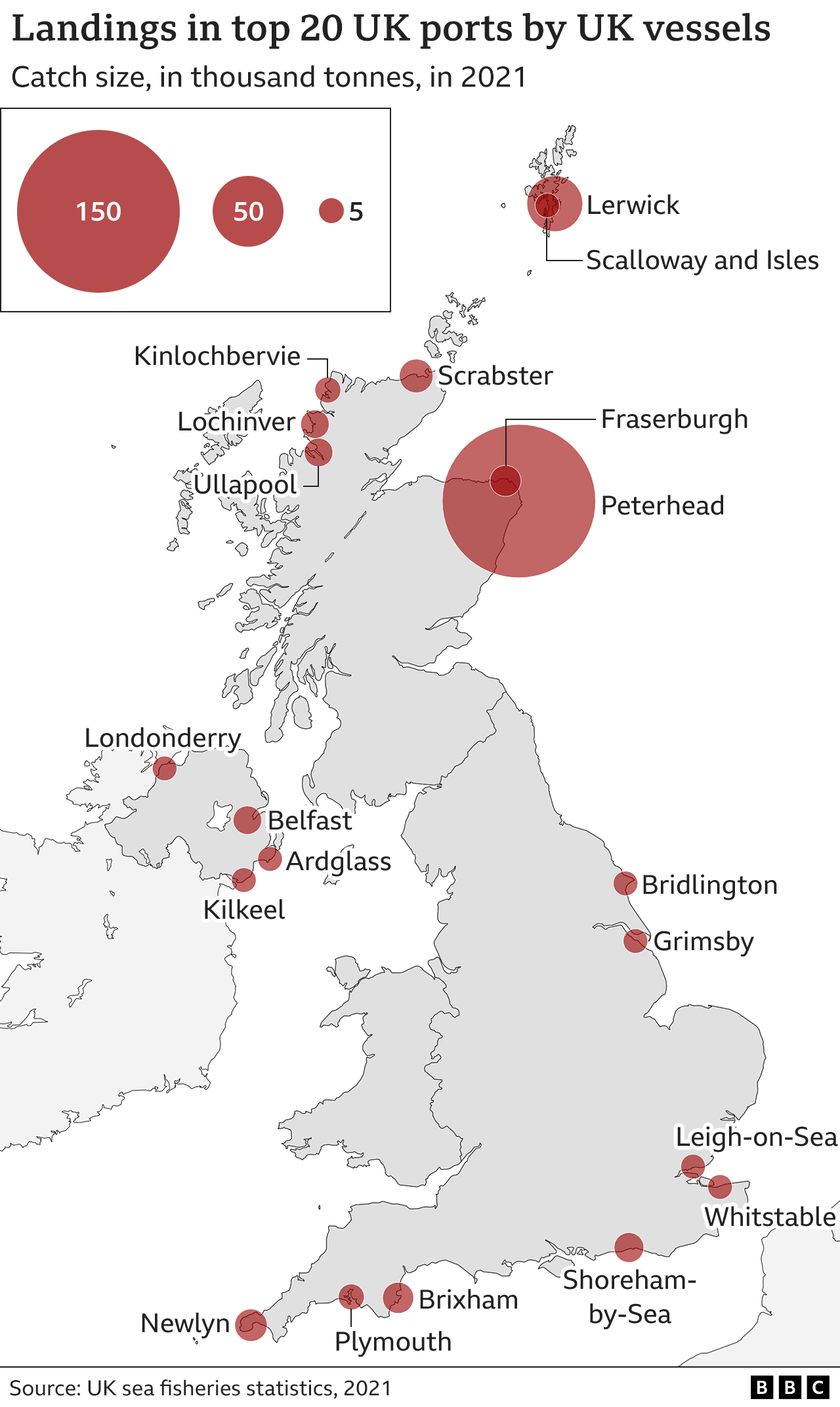

In 2021, Peterhead and Lerwick got more than 83% of the extra catch - 25,000 of those 30,000 extra tonnes.

Ports in north-east England - Hull, Grimsby and Bridlington - as well as in the south-west - Plymouth and Newlyn - all saw decreases on their 2019 catches.

Why did some areas do better and some worse?

Dr Stewart says the new quota system is skewed towards a small number of species, benefiting those places where they're fished.

"The gains to the UK in terms of tonnage and value are highly concentrated. Western mackerel, which is fished off the north coast of the UK and landed in places like Peterhead, accounts for about 30% of the change in overall value."

The Scottish Pelagic Fishermen's Association (SPFA) represents 22 boats which fish for mackerel and herring in the north-east Atlantic.

"If you asked me if our fishermen would prefer to be back in the EU, the answer would be a huge 'absolutely not'," said chairman Ian Gatt.

'I had to make 72 fishermen jobless'

It's a different story for Jane Sandell of UK Fisheries, a foreign-owned company based in Hull.

Its trawlers fish in Norwegian waters in the North Atlantic and 95% of their catch is cod which goes to UK fish and chip shops.

Ms Sandell says before Brexit (when the UK share of the fish in Norwegian waters was determined by EU-Norway negotiations), the company would catch about 15,000 tonnes of cod a year and employed 106 crew, most from the north-east of England.

Jane Sandell, CEO of UK Fisheries, in front of the last trawler in her company's fleet

In 2022, their catch halved. She blames the fishing deal the UK negotiated with Norway, external in 2021.

Announcing it, the government said UK boats would "gain access to 30,000 tonnes of white fish" in 2022 - the limit for cod was set at 7,000 tonnes a year.

Ms Sandell says: "From the middle of 2021 to the end of 2022, I had to make 72 fishermen jobless. That's the worst bit, because it's people's livelihoods."

Gary Taylor, a former government fisheries negotiator, says: "The position - when the UK was part of the EU - was that we were very much a net beneficiary of the deal with Norway.

"We gained significant amounts of Arctic cod. That was drastically reduced under the current [UK-Norway] deal."

'No change' in Cornwall

One of the main requests from the fishing industry in Cornwall was to exclude French and other EU boats from the zone between six and 12 miles off the Cornish coast.

The Brexit deal did not do this - which was "extremely painful", according to Chris Ranford from the Cornish Fish Producers Organisation which represents about 170 vessels fishing for over 40 different species of fish.

"Our boats are often affected by the weather and the sea conditions. They are not able to go to the sea at certain times of the year because they don't have engine capacity or the size of the boat to do so. During those times, we get a lot of foreign vessels operating up to the six mile line."

He's also sceptical about the post-Brexit increase in fish quotas.

"Us in the south-west of England, fishing relatively close to the shore, haven't seen anywhere near as much as a 25% increase. We are looking at very minimal numbers."

In Devon, Juliette Hatchman of South Western Fish Producers highlighted post-Brexit trade.

Although the trade deal avoided tariffs (taxes) on UK seafood exports to the EU, she says there are still problems:

"The sheer cost of all the additional export paperwork is quite eyewatering. Whilst the extra costs have in part been absorbed into the selling prices to some EU customers, this has clearly resulted in the loss of some long-standing smaller EU (namely French) customers."

Reporting by Tamara Kovacevic, graphics by Erwan Rivault