Isle of Wight-size iceberg breaks from Antarctica

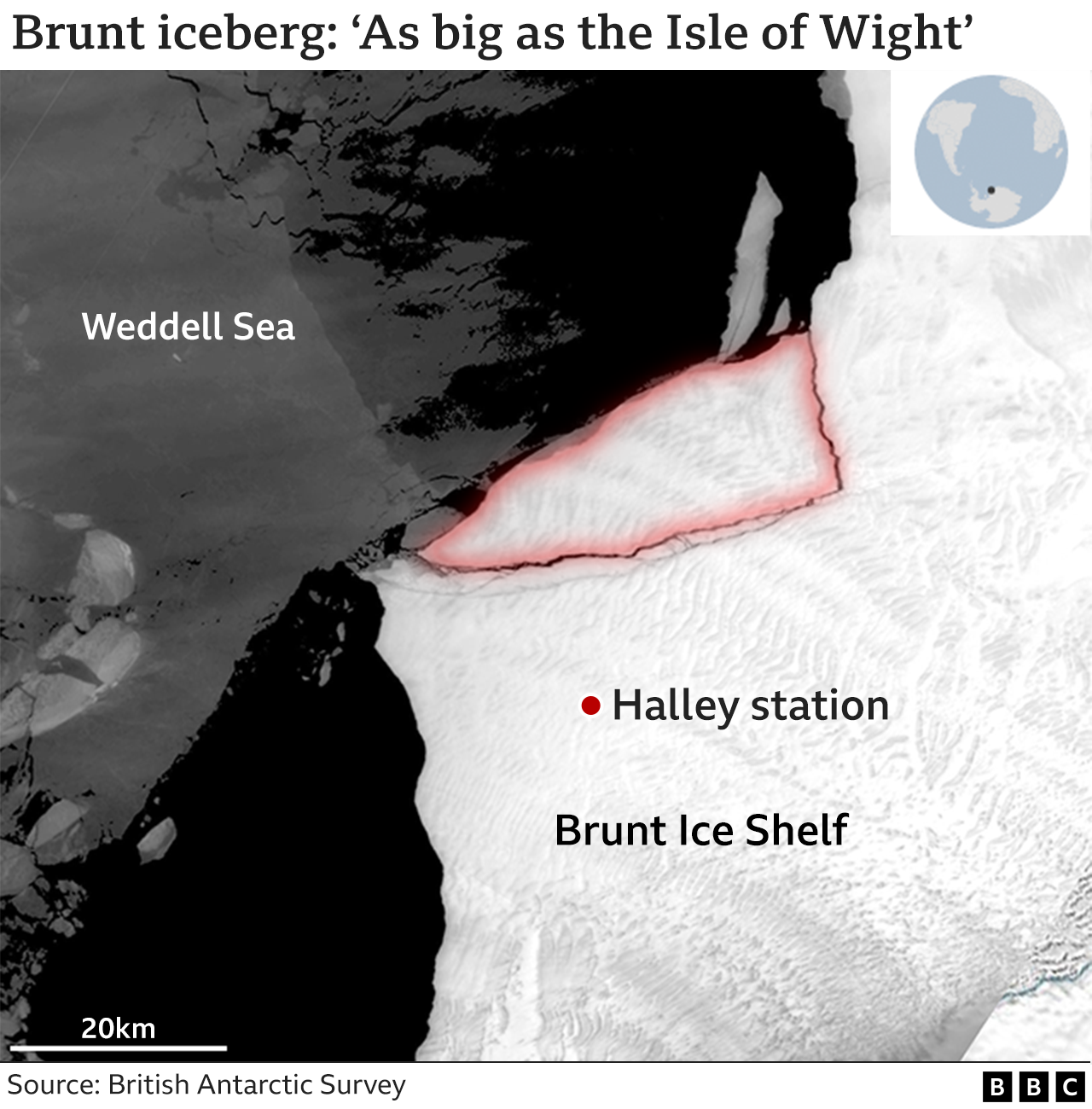

Satellite imagery shows clear water all around the berg (outlined in red)

- Published

Another big iceberg has broken away from an area of the Antarctic that hosts the UK's Halley research station.

It is the third such block to calve near the base in the past three years.

This new one is not quite as large, but still measures some 380 sq km (145 sq miles) - roughly the size of the Isle of Wight.

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) took the precaution of moving Halley in 2017 because of concerns over the way the local ice was behaving.

Its buildings were shifted on skis to take them away from immediate trouble.

The station is also now routinely vacated during the long dark months of the southern winter. The last personnel were flown out in February.

Scientists probe the secrets of mega icebergs

- Published17 April 2024

Rapid ice movement monitored under UK polar base

- Published13 September 2023

Halley sits on top of the Brunt Ice Shelf, which is the floating protrusion of glaciers that have flowed off the continent into the Weddell Sea.

This shelf will periodically shed icebergs at its forward edge and it is currently going through an extremely dynamic phase.

In 2021, the shelf produced a berg the size of Greater Paris (1,300 sq km/810 sq miles) called A74, followed in 2023 by an even bigger block (1,500 sq km/930 sq miles) the size of Greater London, known as A81.

The origin of the new berg goes back to a major crack that was discovered in the shelf on 31 October, 2016. Predictably, it was nicknamed the "Halloween Crack".

A further fracture perpendicular to Halloween has now cut a free-floating segment of ice that has already begun to drift out into the Weddell Sea.

Halley was moved in 2017. Even so, it is less than 15km from the edge of the Brunt

BAS was alerted to the breakaway thanks to two GPS instruments that had been planted on the anticipated berg.

"They're single frequency GPSs, so they're not particularly accurate, but they tell you when something major happens, and we saw movement of a few hundred metres within an hour, which is a good indication the berg had broken free of the ice shelf," said glaciologist Dr Oliver Marsh.

Satellite imagery confirms the GPS data. The berg is surrounded by seawater on all sides.

The loss of so much ice from the Brunt structure these past three years has triggered a rapid acceleration in the shelf's seaward movement.

Historically, it has flowed forward at a rate of 400-800m (1,300-2,600ft) per year. It is now moving at about 1,300m (4,300ft) a year.

Long history

The Brunt has hosted a British base since 1956. It is one of the two main centres for UK science on the continent, the other being at Rothera on the other side of the Weddell Sea.

BAS and the UK's Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office have a clear interest therefore in understanding what the recent calving events mean for the long-term safety of the station, and a project was initiated earlier this year to investigate the forces that are driving Brunt's present activity.

"This latest calving reduces the Brunt Ice Shelf to its smallest observed size," commented remote sensing specialist Prof Adrian Luckman, from Swansea University.

"Since the calving of Iceberg A81 in January 2023, the ice shelf is also more dynamically active than previous years. We may be observing the end of a dynamic readjustment, but only time will tell if things settle down now."

BAS scientists are investigating why Brunt has produced so many bergs of late

Icebergs are named according to a classification system run by the US National Ice Center (USNIC), which divides the Antarctic into quadrants.

Because the Brunt is in the eastern Weddell Sea, its bergs get an "A" designation. "83" is the next number available in the series of large calvings in this sector.

This means the USNIC will probably issue a bulletin in the next day or so announcing the existence of A83.

Only very large bergs get named. Their scale means they must be tracked because they pose a navigation hazard.