Researchers using ultrasound to treat OCD symptoms

Researchers demonstrate on a colleague how the scalp is covered with gel ready for the ultrasound transducer to be placed on the head.

- Published

Scientists in Devon are trialling the use of ultrasound to stimulate areas of the brain which trigger Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) symptoms.

Experts at the Brain Research and Imaging Centre at the University of Plymouth said they want to prove that transcranial stimulation can treat networks in the brain that do not communicate properly.

If the trial is successful, researchers hope the treatment will be used to reduce the repetitive behaviour and intrusive thoughts associated with OCD.

Ultrasound is commonly used as a diagnostic tool to scan parts of the body - but this research aims to prove it can also be used to treat OCD.

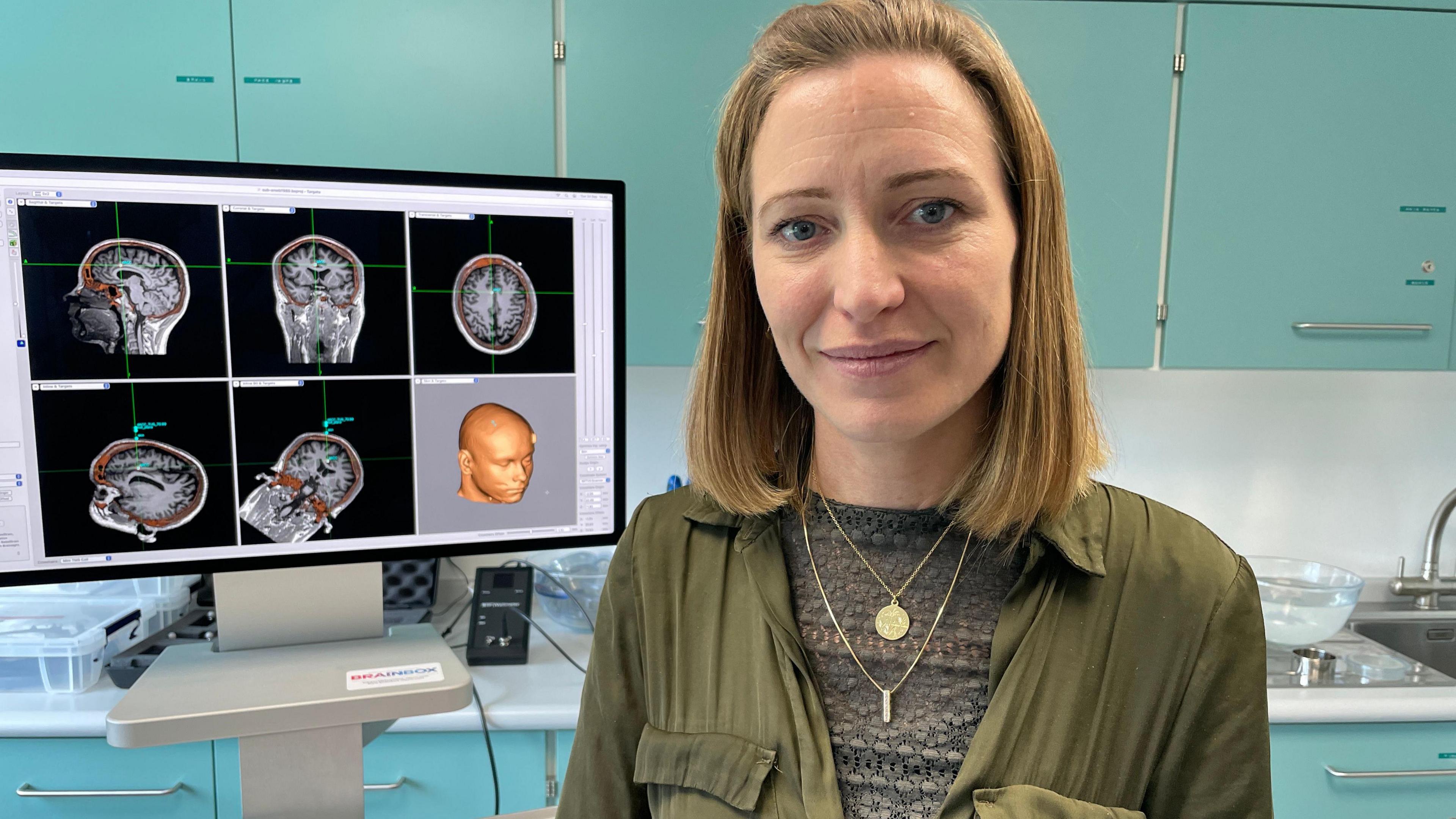

Dr Elsa Fouragnan is the lead investigator for the OCD trial at the University of Plymouth

Principal investigator Dr Elsa Fouragnan, head of the non-invasive brain stimulation lab, said her team was using ultrasound to identify the dysfunctional areas of the brain that triggered OCD.

“We use ultrasound to actually induce neuroplasticity in the network that’s underlying the participant's OCD issue," she said.

The 60 participants in the trial are being given initial scans to identify the areas that needed ultrasound treatment.

The researchers said although everyone experiences obsessive thoughts or compulsive behaviours at times, OCD can lead to a cycle that interrupts everyday life and affects a person's mental health.

No drugs involved

Participant Matthew Bennetts said he only discovered he had OCD during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown when his flatmates noticed his repetitive behaviour.

“One of them noticed I was doing things like checking the doors, checking the gas hobs," said Mr Bennetts.

"I was repeating stuff in numbered patterns, and they asked me if I had OCD."

Mr Bennetts has received four ultrasound sessions and said he was hopeful the treatment was reducing his symptoms.

The scientists claim the risks are small during the trial because the ultrasound treatment is non-invasive and not long lasting.

It does not involve drugs or blood tests.

People who are already on medication for their OCD will not be able to take part in this phase of the research as it could affect its outcome, researchers said.

Related topics

- Published2 January 2023

- Published8 September 2024

- Published20 July 2024