How the hologram came to be invented in Rugby

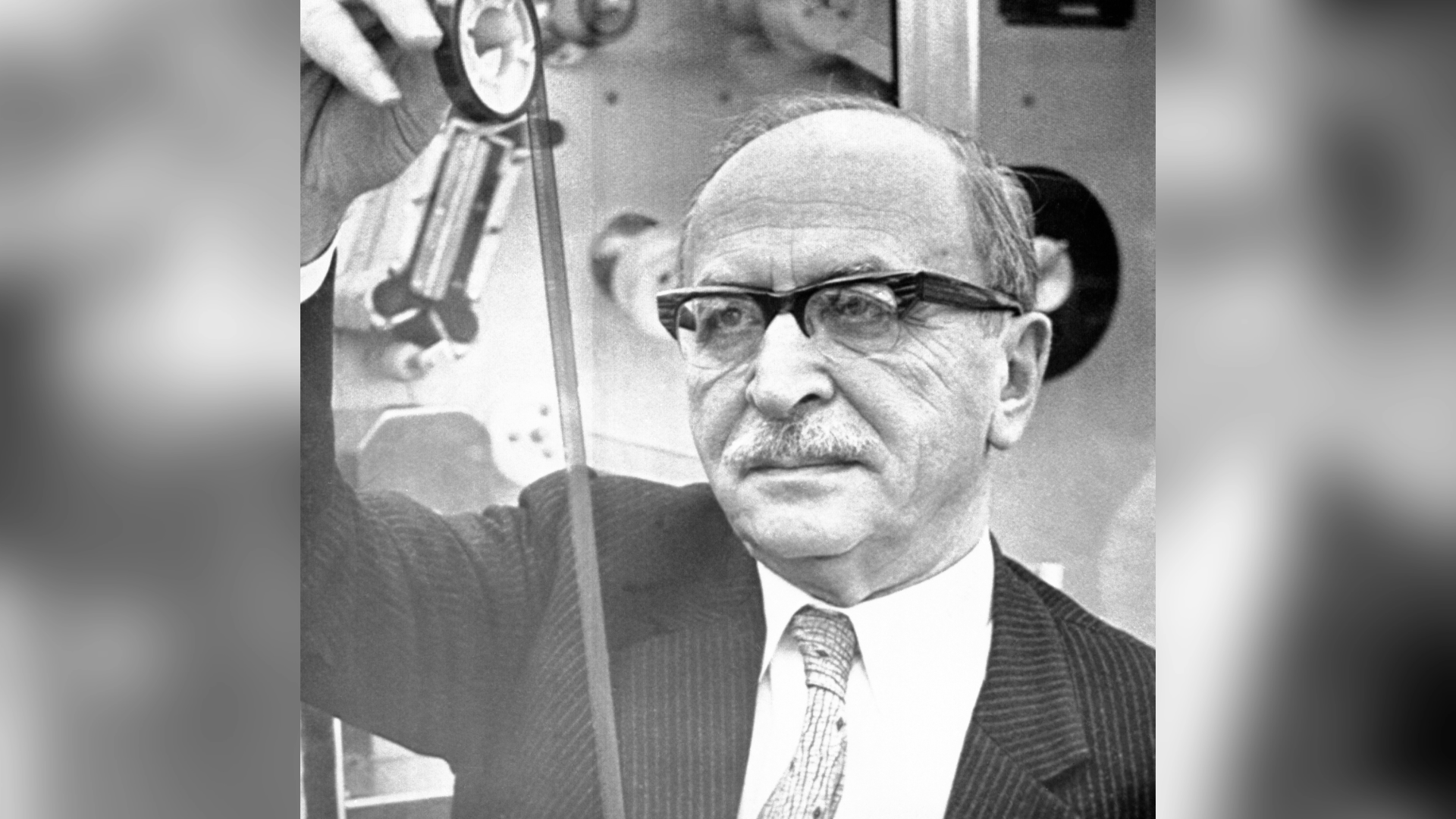

Holograms were invented in Rugby by scientist Dennis Gabor, who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1971 for the idea

- Published

With recent advancements in artificial intelligence, it is predicted holograms will become an ever-greater part of our future lives.

A type of image made with a laser, holograms can make objects appear in three dimensions, rather than two-dimensional or flat.

The "radical concept" was invented in Rugby by scientist Dennis Gabor, who won the Nobel Prize for Physics for his idea in 1971.

Gabor was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1900 and developed an interest in physics in his early teens, before moving to the UK to escape the Nazi regime.

The BBC's Secret Warwickshire series is exploring the story of the hologram's inventor, and the continuing relevance of his innovation today.

While he was growing up, Gabor's father built him a laboratory at home where he would conduct experiments.

Prof Eric Yeatman from the University of Glasgow said it was an exciting time for physics.

"In those days, I think children had access to things we wouldn't really consider safe nowadays," he said.

Prof Eric Yeatman says Gabor's invention was "a completely radical concept"

There were not many career prospects for physicists at the time, so Gabor was encouraged to take up engineering for his university studies in Berlin.

However, when Hitler came to power, he did not feel safe in Germany due to his Jewish background, so returned to his native Hungary.

Concerned about ongoing persecution, in the 1930s he moved to England. In 1933, he was invited to work at engineering company British Thomson-Houston, based in Rugby.

It suited his area of interest, and the firm allowed him to be inventive, Prof Yateman said.

He explained it was Gabor's work on improving the resolution of the electron microscope that led him to the idea of holography in 1951, which was to become his most famous work.

"It was like a sort of bolt out of the blue, it was a completely radical concept," Prof Yeatman said.

Edit Kruk says Gabor's work continues to be relevant

Edit Kruk, an experiential strategist from Hypervsn, a company at the cutting edge of the latest advancements in holography, said Gabor's legacy continued to find many applications in the modern world today.

"This actually spans so many different sectors – from automotive, healthcare, media, pop-up experiences, galleries – you name it," she said.

"I would say the greatest impact is attention. Nothing captures the attention like seeing something so bright, so beautiful and hovering in mid-air.

"In the automotive industry, being able to see a 1:1 model of a car and being able to customise it in real time but also to be able to see it in 3D in front of you without having to pull out the actual car."

Rugby: The home of the Hologram

Examples of existing uses include virtual sales assistants in department stores, and the ABBA Voyage concerts, where the four members of the band are holograms.

Holograms could also be used to help interior design firms or architects show people how building or renovation projects could look when completed, Ms Kruk said.

Gabor also predicted risks, however, including the notion that AI and holograms could potentially replace some types of employment.

The scientist died in 1979 in London. An English Heritage blue plaque was later placed at his former home on Queen's Gate in Kensington, where he lived from 1949 until the early 1960s.

Get in touch

Tell us which stories we should cover in Warwickshire

Follow BBC Coventry & Warwickshire on BBC Sounds, Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external.

Related topics

- Published23 December 2024

- Published20 October 2023

- Published10 November 2024