Eating on the hoof: London's long history of street food

- Published

Street food as we know it has a decidedly international flavour. Aromatic Ethiopian stew, mildly spiced Egyptian falafel, bao buns and po'boys - taste buds can travel the world in a lunch hour.

London dominates the UK's street food scene, home to six of the country's 10 most popular locations, external, including the top three markets of Borough, Broadway and Seven Dials.

According to the Nationwide Caterers Association, "the street food revolution took grip of London and spread throughout the nation.

"And now it’s everywhere."

Soup - warm, cheap and easily doled out - was a street food staple

Street food, though, has been a thing in the capital ever since both streets and food existed.

People with no kitchen at home could get a warm meal by patronising one of the numerous hawkers selling their wares.

London Particular (a thick soup), eel jelly, batter pudding, oysters, and watercress were all eaten on the hoof - and sometimes with the hoof, in the form of boiled pigs' trotters.

Here are some of the delights of the capital's long history of eating on the street.

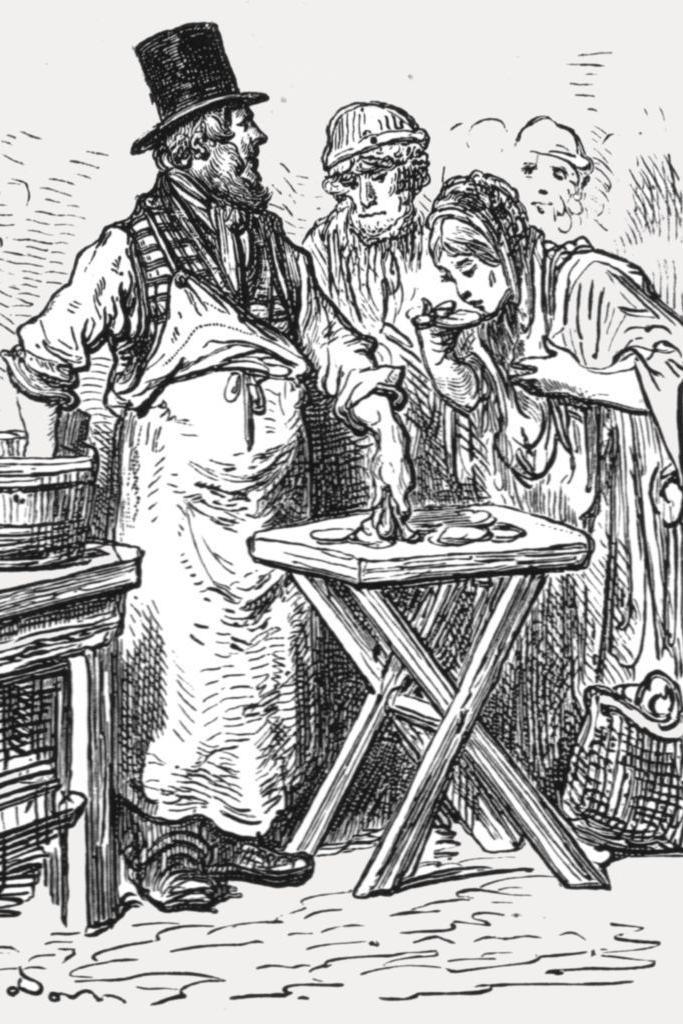

A cartoon from George Cruikshank's Almanack shows Oyster Day - with boys building a grotto in the bottom-right corner

Oysters

Famously going from cheap food for poor people to luxury food beloved of investment bankers, oyster have been eaten in London since toga-clad Romans strolled about enjoying the tasty bivalve molluscs (shells are routinely found in excavations within the Square Mile).

Journalist Henry Mayhew, in his observational book London Labour and the Poor, published in the 1840s, said costermongers sold 24,000,000 oysters a year, and "these, at four a penny, would realise the large sum of £129,650".

Oyster Day was the day at the beginning of August when the bivalve molluscs would be brought into the fish markets for the first time of the year.

Described in the Illustrated London News in 1851 as a "red letter day for the city's poor", Oyster Day also provided the raw materials for Grotto Day.

Grotto Day was described in The Leisure Hour (a weekly magazine) in 1856: "No sooner do you walk out in the morning, in whatever direction you will, than you are saluted with the cry of, 'please to remember the grotto," emanating from some unwashed, untended little wanderer, who runs capering before you, clutching in his dirty fingers an oyster-shell, which serves him as a begging-dish.

"If you escape from one, it is only to fall into the hands of another, or of a dozen or a score of others, awaiting you round the corner."

The grottos were built by street children from "inverted oyster-shells piled up conically with an opening in the base, through which, as night approaches, a lighted candle is placed within, when the effect of the light through the chinks of the shelly cairn is very pretty".

Oyster Day is now recognised internationally as 5 August, external.

Sam Weller said in Dickens's The Pickwick Papers, "poverty and oysters always seem to go together"

How chocolate became the winter beverage of choice

- Published11 December 2023

London's 391 years of going bananas for bananas

- Published10 April 2024

Watercress is still a staple on some of London's grandest sandwich platters

Watercress

The peppery greenery was nicknamed "poor man's bread" by the Victorians, and street sellers in London sold bunches of it to be eaten from the hands as a snack.

The flavour comes from mustard oil released as it is is chewed, and has a cooling effect.

A species of aquatic flowering plant in the cabbage family, it is one of the few fruits or vegetables that has not been altered by breeding or selection - so the watercress we can scoff now is the same as that enjoyed in Greek and Roman times.

Afternoon tea at some of London's most famous hotel - the Langham, the Ritz, Claridges and the Savoy all feature watercress in their sandwich selections.

Gram for gram, watercress contains more vitamin C than oranges, more calcium than milk and more iron than spinach.

Not just healthy to consume, external, it is also good to apply externally - researchers at Exeter University have launched a skincare range, external.

Watercress - good for eating, good for rubbing on the face, as these women at Covent Garden demonstrate

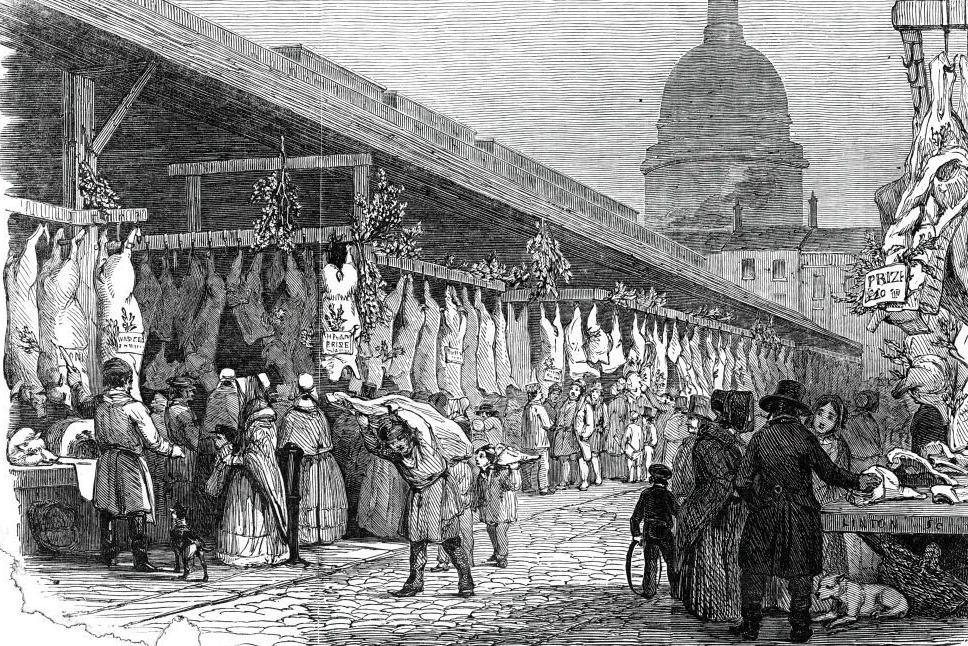

Haunches for meat for sale at Newgate Market - but how much was broxy?

Broxy

Perhaps the least alluring dish was broxy - a butcher's term for the meat of any animal that dropped dead from disease.

Sheep were particularly prone to infectious illnesses and so mutton was often the cheap filler of hard-up stomachs.

Another popular meaty treat was pigs' trotters, which could be held in the hand while the diner sucked the meat and fat from the bones.

Thick and yellow, the fog named after the soup became a soup named after the fog

London Particular

In the 19th Century, London Particular - a thick soup - was a street food staple in stalls and taverns of the capital.

Made from yellow split peas, ham, and whatever other vegetables were hanging around, the name comes from the thick smog known as a "pea-souper", which was turned yellow by the coal fires and industrial chimneys.

In Bleak House, Charles Dickens uses the term “London particular” as a synonym for that foul smog.

So the fog named after the soup eventually became a soup named after the fog.

According to experts, it should be thick enough to support a spoon standing upright, which makes it less of a soup and more of a mush.

According to the Taste Atlas website, London Particular is served at a number of high-end restaurants, external in the capital - but it might be more in keeping with the spirit of the original to make your own.

And who wouldn't enjoy a dish named after a deadly miasma of pollutants?

One of the glasses used to pass on a penny lick of tuberculosis

Hokey Pokey

More commonly known now as ice-cream sellers, the Hokey Pokey barrows were originally divided so as to accommodate the vagaries of the London climate.

Half the cart was for selling gelato and half for baked chestnuts - and both could be offered at the same time.

The vendor's cry of "Hokey Pokey" was the Anglicisation of the Italian "ecco uno poco", meaning "here is a little".

Ice-cream was available to buy in the form of "penny licks" - a small serving in a returnable glass or shell.

The glass, once it had been licked of ice-cream would then be reused for the next customer - often with only a perfunctory swill or wipe to clean it.

The use of penny lick glasses was banned in 1898 - a decade after a medical report suggested the unhygienic vessels were an ideal conduit for tuberculosis.

"You had eels with your jelly? Luxury"

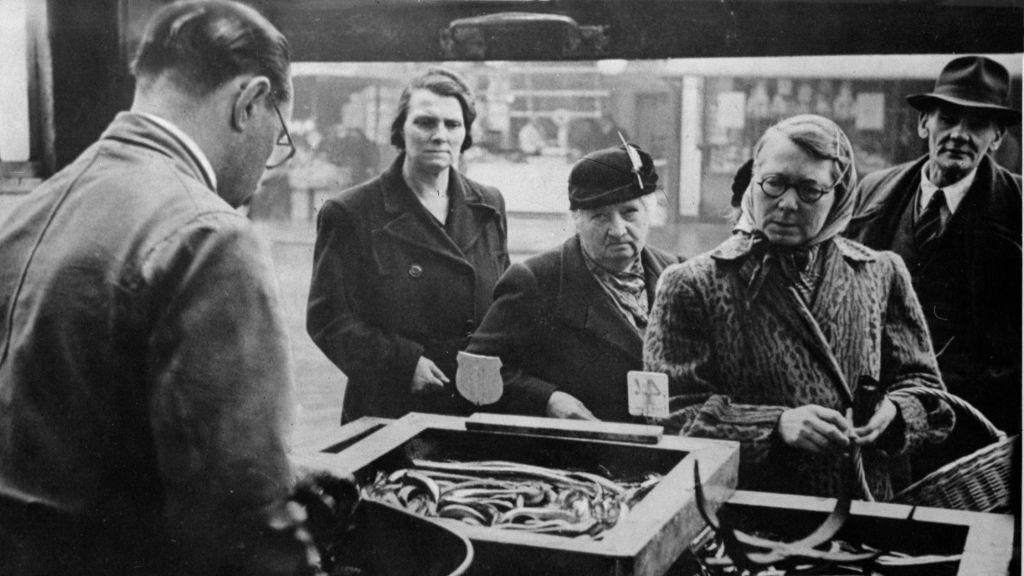

Eel Jelly

Not to be confused with jellied eel, eel jelly (jellied eel without the eel, and served hot as liquid rather than cold as jelly) was described in 1902 by Living London; a Chronicle of London Variety.

"Here in all its glory the eel-jelly trade is carried on.

"In great white basins you see a savoury mess... the local luxury is ladled out to a continuous stream of customers.

"Many a time on a terribly cold night have I watched a shivering, emaciated-looking man eagerly consuming his cup of eel-jelly, and only parting with the spoon and crockery when even the tongue of a dog could not have extracted another drop from either."

The jelly is formed when the heating process releases proteins, like collagen, into the cooking stock, which solidify upon cooling.

Looks like London Particular. Is not London Particular

Related internet links

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external