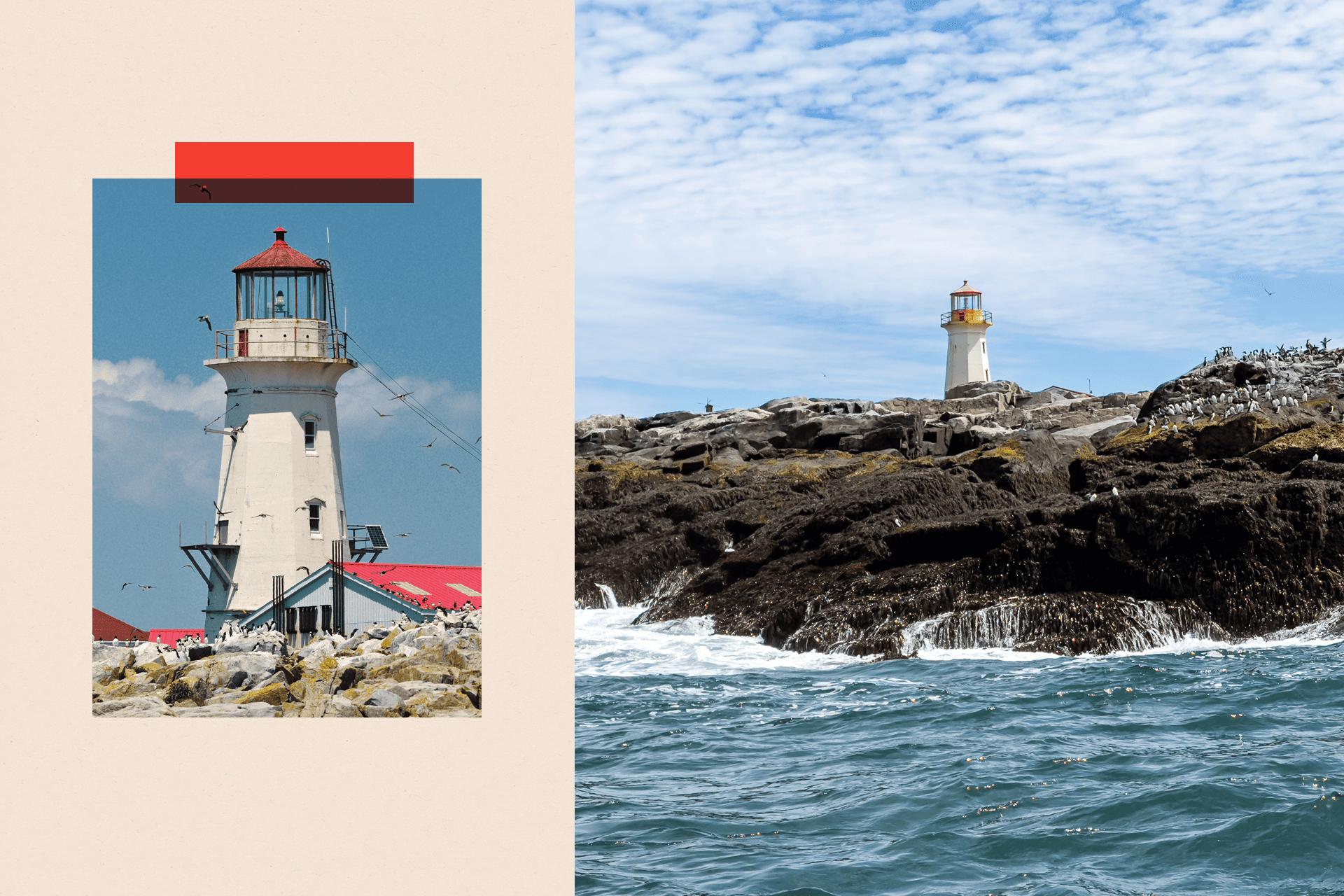

Machias Seal Island is a tiny dot on maps of North America. But the fogbound rock is significant for its location in an area known as the "Grey Zone" – the site of a rare international dispute between Canada and the United States.

The two neighbours and long-time allies have each long laid claim to the island and surrounding water, where the US state of Maine meets Canada's New Brunswick province – and with that claim, the right to catch and sell the prized local lobsters.

John Drouin, a US lobsterman who has fished in the Grey Zone for 30 years, tells of the mad dash by Canadian and American fishermen to place lobster traps at the start of the summer catching season each year.

"People have literally lost parts of their bodies, have had concussions, [their] head smashed and everything," he says.

The injuries have been caused when lobstermen have been caught up in each other's lines. He says one friend lost his thumb after it became caught up in a Canadian line, what Mr Drouin calls his battle scar from the Grey Zone.

Canada and the US have disputed the sovereignty of the 'Grey Zone' since the 1700s

The 277 square miles of sea around Machias Seal Island has been under dispute since the late 1700s – and in 1984, an international court ruling gave both the US and Canada the right to fish in the waterway.

It has stood as a quirk – an isolated area of tension in what had been, until now, an otherwise close relationship between the two countries.

But that could all be about to change.

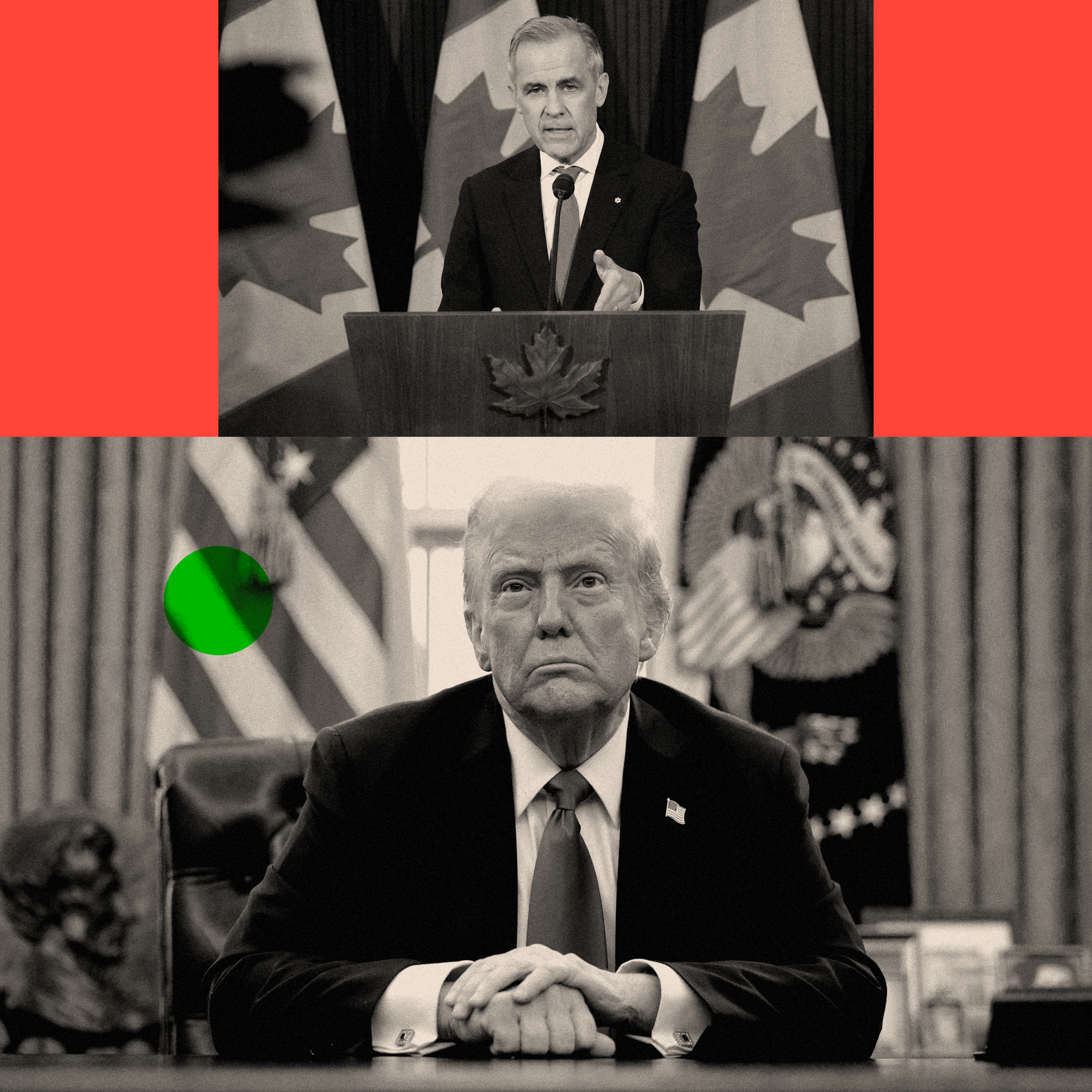

US President Donald Trump's return to the White House, steep tariffs on Canadian imports and rhetoric about making the country the 51st state has sparked a series of fresh flashpoints, with the possibility that he may ultimately wish to subsume Canada into the US hanging over everything. Amid the biggest shift in the relationship between the two countries in decades, the question is, what does he really want from Canada?

Lobster wars

Cutler, Maine, is the closest US town to the Grey Zone. It has a collection of scattered houses, one supply store and, for good reason, a lobster wholesaler.

Aside from a few big-city retirees and holiday-goers, Cutler owes its existence to the bountiful crustaceans that inhabit the offshore waters. And for the lobstermen of Cutler, the international limbo of the Grey Zone is their everyday reality, as they scatter their traps along the bottom of the Gulf of Maine to catch the prized lobsters and bring them to market.

During lobster season, the Grey Zone is packed with boats and buoys marking the location of their traps. When the waters get crowded and livelihoods are at stake, things can get ugly.

Some lobstermen, such as John Drouin (pictured in Cutler), have encountered skirmishes in the 'Grey Zone'

"Do we like it? Not in the least," says Mr Drouin. He has caught lobsters in the Grey Zone for 30 years. "I will continue to complain about it until I can't breathe anymore."

Another Maine lobsterman, Nick Lemieux, said he and his sons have had nearly 200 traps stolen in recent years – and he blames their rivals to the north.

"This is our area, and it's all we have to work with," he said. "Things like that don't sit very well with us."

Americans accuse the Canadians of operating under a different, more accommodating set of rules that allow them to catch larger lobsters.

Canadians counter that the Americans have higher catch limits and are surreptitiously fishing in their territorial waters.

The union representing Canada's fishery officials recently complained that Americans have responded to their enforcement efforts with threats of violence – and some of its officers have refused to work in the Grey Zone.

The Machias Seal Island lightstation has lightkeepers on site all year round but the Canadian Coast Guard sends additional technical support if there is an issue with the automated aid to navigation.

The Americans point to US Marines who occupied the island during World War One as their proof of sovereignty.

A series of border disputes

The dispute appears to be going nowhere, but during Trump's first presidency, events in the Grey Zone did not appear to be intruding greatly on the overall warmth between the US and Canada.

When Trump hosted Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the White House in 2017, he spoke about the US-Canada relationship in glowing terms, remarking on the "special bonds" between the two nations that "share much more than a border".

Yet his rhetoric has since changed sharply.

In recent months, Trump has repeatedly called Canada the "51st state" of the US – and the White House has expressed a willingness to open up new areas of dispute all along the US-Canada border.

In September, the president voiced designs on Canadian water in British Columbia in the west of the country, for instance, suggesting it could be piped to drought-parched California: "You have millions of gallons of water pouring down from the north… they have essentially a very large faucet".

Approximately 1,500 miles further east, the Great Lakes could become another site of potential conflict, as US officials told their Canadian counterparts they are considering withdrawing from treaties over their coordinated environmental regulation.

And even further east, a library has become the unlikely setting for a flashpoint: built deliberately to straddle the Vermont-Quebec border as a symbol of cooperation between Canada and the US, the Haskell Free Library and Opera House used to be open to residents from both nations.

However in March, America changed the rules so that Canadians are required to pass through immigration control before they access the building, with the US Department of Homeland Security claiming it was in response to drug trafficking.

Battle for natural resources

Natural resources are another source of dispute. Canada has vast supplies of rare earth metals, gold, oil, coal and lumber – the kind of natural wealth that Trump has long prized.

While Trump has disavowed any desire for Canada's lumber, energy stockpiles or manufactured products, in February Trudeau reportedly told a closed-door meeting of Canadian business and labour leaders that he saw it differently.

"I suggest that not only does the Trump administration know how many critical minerals we have but that may even be why they keep talking about absorbing us and making us the 51st state. They're very aware of our resources, of what we have, and they very much want to be able to benefit from those," the CBC quoted Trudeau as saying.

Jordan Heath-Rawlings, a Canadian journalist and host of The Big Story podcast, believes Trump wants Canadian resources, and that the president's annexation comments should be taken seriously.

"He likes the idea of being the guy to bring in a huge land mass," says Mr Heath-Rawlings. "He probably wants the Arctic, which is obviously going to become much more valuable in the years to come."

Canadians have already been boycotting US products and cancelling holidays there

For Trump, even the US-Canadian border itself is suspect. "If you look at a map, they drew an artificial line right through it between Canada and the US," he said in March. "Somebody did it a long time ago, and it makes no sense."

Needless to say, Trump's comments have rankled Canadian leaders, who warn of the president's ultimate designs on their homeland.

In March, Trudeau accused the US president of planning "a total collapse of the Canadian economy because that will make it easier to annex us".

The previous month, after Trump first announced new tariffs on Canada, Trudeau had said: "Trump has it in mind that one of the easiest ways of doing that [annexing Canada] is absorbing our country. And it is a real thing."

If US territorial ambitions for Canada are, in fact, a "real thing", it presents a simple, vexing question. Why? Why would the US, which has had the closest of diplomatic, military, economic and cultural ties with its northern neighbour for more than a century, put all of that at risk?

Exception rather than the norm

Some see a pattern in Trump's designs on Canada, Greenland and the Panama Canal – one that reflects a dramatic change in how the US sees itself in the world.

It has been most clearly articulated by US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who said in January that the post-World War Two dominance of the US was more the exception than the norm.

"Eventually you were going to reach back to a point where you had a multi-polar world, multiple great powers in different parts of the planet," he said. "We face that now with China and to some extent Russia, and … rogue states like Iran and North Korea."

According to Michael Williams, professor of international affairs at the University of Ottawa, if the current Trump administration thinks that American world dominance is no longer possible or even desired, the US might pull back from far-flung conflicts and European commitments.

Instead, says Prof Williams, the US would prioritise its "territorial core", creating a continental fortress of sorts, insulated on both sides by the vastness of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

"If this is your plan, you seek to control key geographic choke points," he says. "You maximise access to natural resources, of which Canada has plenty, and you reshore industry whenever possible."

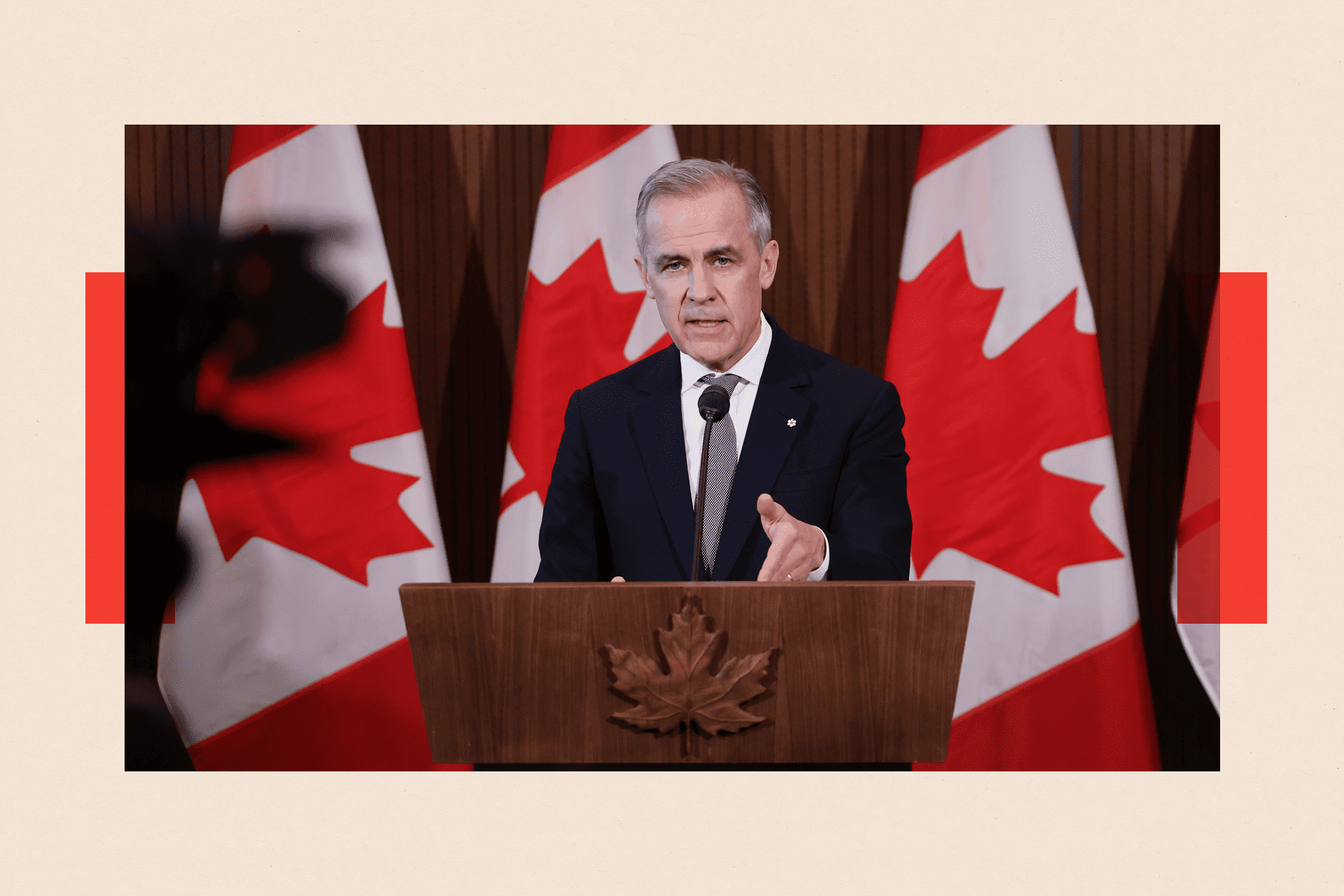

Mark Carney recently said that the long-standing relationship Canada had with the US is now over

Such a geopolitical outlook is hardly new. In the 1820s, US President James Monroe articulated a new global order in which America and Europe confined themselves to their own hemispheres.

But it does represent a remarkable shift in US foreign policy since the end of World War Two.

A plan or a whim?

Prof Williams acknowledges that it's difficult to figure out exactly what the US president is thinking – a view wholeheartedly endorsed by John Bolton, who served as Trump's national security adviser for more than a year of his first presidential term.

"Trump has no philosophy," he says. "He gets ideas, but does not follow a coherent pattern. There is no underlying strategy."

The president is currently fixated on minerals and natural resources, he said, but Mr Bolton argues the best way to go about doing that is through the private sector, not by floating the idea of annexing an ally. Canada, for its part, has offered to work with US companies on joint mining partnerships.

Prof Williams and Mr Bolton agree that whatever the motivations behind Trump's designs on Canada, the diplomatic damage that's being done will be difficult to undo – and the possibility of unanticipated consequences is high.

Boycotts and cancelled trips

"Trump likes to say in a lot of contexts that other people don't have any cards," says Prof Williams. "But the further you push people to the wall, the more you may find that they have cards that you didn't know they had – and they might be willing to play them. And even if you have more cards, the consequences of doing so can easily spiral out of control in some really bad ways."

Canadians have already been boycotting US products and cancelling winter trips south, which has had an impact on tourist communities in Florida.

"We're not looking for a fight, but Canada's ready for one," says Mr Heath-Rawlings.

The idea that the trust between the US and Canada has been broken is one that's been embraced by the country's new prime minister, Mark Carney, as a general election looms.

"The old relationship we had with the United States based on deepening integration of our economies and tight security and military cooperation is over," he said recently. "I reject any attempts to weaken Canada, to wear us down, to break us so that America can own us."

Back in the 19th Century, territorial conflicts and flare-ups along the US-Canada border were a more frequent occurrence. Americans made multiple unsuccessful attempts to capture Canadian territory during the 1812 War.

In 1844, some Americans called for military force if the UK wouldn't agree to its claims in the Pacific Northwest.

The 1859 "pig dispute" involved contested islands near Vancouver and the unfortunate shooting of a British hog that had intruded on an American's garden.

All that seemed the stuff of dusty history books, where the Grey Zone was a diplomatic oddity – an exception to a peaceful norm in the modern world of developed and integrated democracies.

But that calm is now broken, and no one is sure where these stormy waters will lead either country.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.