How assisted dying has spread across the world and how laws differ

- Published

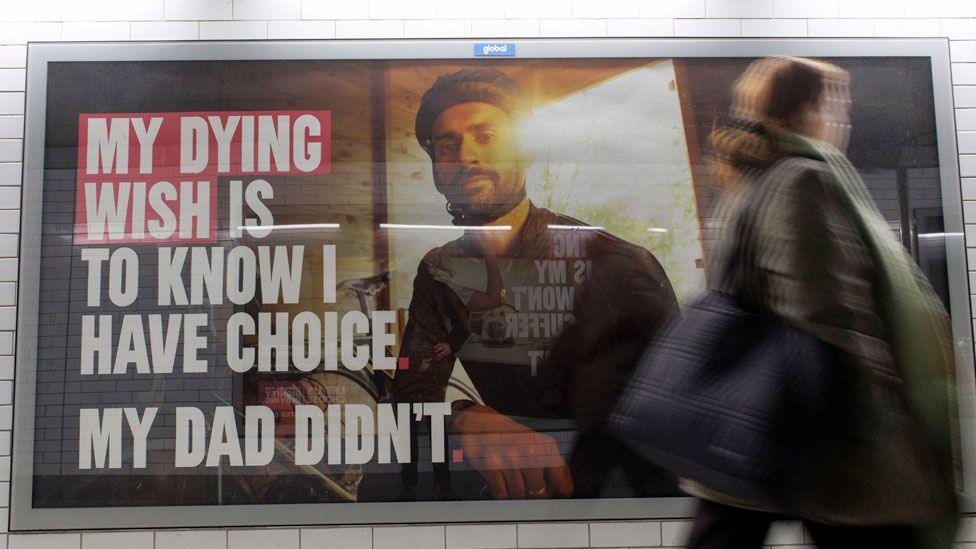

For the first time in almost a decade, MPs will vote on Friday on giving terminally ill adults in England and Wales the right to have an assisted death. While it’s something that remains illegal in most countries, more than 300 million people now live in countries which have legalised assisted dying.

Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Spain and Austria have all introduced assisted dying laws since 2015 – when UK MPs last voted on the issue – some allowing assisted death for those who are not terminally ill.

The proposed bill in England and Wales comes with safeguards supporters say will make it the strictest set of rules in the world, with patients needing the approval of a High Court judge. Critics on the other hand say changing the law would be a dangerous step that would place the vulnerable at risk. They argue the focus should be on improving patchy access to palliative care.

Ahead of Friday's vote, we look at assisted dying laws in North America, Europe and Australasia.

More on the assisted dying vote

The US

Across the US, assisted dying - which some critics prefer to call assisted suicide - is legal in 10 states, as well as in Washington DC. Oregon was one of the first places in the world to offer help to die for some patients, in 1997, and so has more than 25 years’ experience. It has become the model on which other US assisted dying laws have been framed.

In Oregon, assisted dying is open to terminally ill, external, mentally competent adults expected to die within six months - and must be signed off by two doctors. Since 1997, external, 4,274 people have received a prescription for a lethal dose of medication - with 2,847 (67%) deaths.

Two thirds of patients in the state, external who asked for help to die last year had cancer. Around one in 10 had a neurological condition and about the same proportion had heart disease. Of the 367 patients who took a lethal dose of medication last year, the vast majority (91.6%) said loss of autonomy was a key concern, external, while others cited:

Loss of dignity - 234 patients (63.8%)

Losing control of bodily functions - 171 (46.6%)

Concern about being a burden on family and friends - 159 (43.3%)

Inadequate pain control - 126 (34.3%)

Financial implications of treatment - 30 (8.2%)

In Oregon, as in other US states that permit assisted dying, the lethal medication must be self-administered - the same is proposed in England and Wales. Around one in three of those prescribed a lethal dose don’t go ahead with it.

Oregon is important for supporters of assisted dying in England and Wales as they point out it has remained restricted to terminally ill adults since its introduction. However, opponents say some of the rules have been relaxed. A residency requirement has been lifted, which means it is open to people from outside the state. The number of assisted deaths has also risen substantially over the years.

Canada

Canada is the country often cited by opponents of assisted dying as an example of the so-called "slippery slope" - a place where assisted dying has been extended and made available to more people since it was first brought in. Medical assistance in dying (Maid), external was introduced in 2016, initially just for the terminally ill.

This was amended in 2021 and extended to those experiencing "unbearable suffering" from an irreversible illness or disability. It’s still due to become available to those with a mental illness in three years, despite delays.

Critics say the more the law is widened, the more disabled and vulnerable people will be put at risk. There has also been a dramatic growth in the number of people using Maid. Four in 100 deaths in Canada are now medically assisted, external, compared to about one in 100 in Oregon.

Kim Leadbeater, the MP who proposed the assisted dying bill in Westminster, says the Canadian system is not what is being debated for England and Wales, where eligibility would be restricted to the terminally ill.

Europe

Across Europe, six countries have some form of legalised assisted dying: Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Spain and Austria. In all of them - unlike the proposals in England and Wales - help to die is not restricted to the terminally ill.

Switzerland was the first country in the world to create a “right to die” when it made assisted suicide legal in 1942. It is one of the few countries which allows foreigners access to help to die via organisations like Dignitas, in Zurich. More than 500 Britons have died at Dignitas, external in the past two decades, including 40 last year. The lethal medication must be self-administered.

The Netherlands and Belgium both legalised assisted dying more than 20 years ago for patients experiencing unbearable suffering from an incurable illness, including mental health issues. It has since been extended to children - the only European countries to allow this. Both allow euthanasia - or physician-assisted dying.

Most recently, Spain and Austria have legalised assisted dying for both terminal illness and intolerable suffering. In Austria, the drugs must be self-administered, whereas in Spain a medical professional can administer them.

Despite the variation, what’s clear is that eligibility for assisted dying is far wider across Europe than is being proposed anywhere in the British Isles. MSPs at Holyrood are to debate a similar bill covering Scotland as that being voted on at Westminster.

A bill to allow terminally ill adult patients to die if they have 12 months or less to live has nearly passed all its stages in the Isle of Man parliament. The legislation is likely to get Royal Assent next year and the first assisted death on the island could happen in 2027. There is a residency requirement of five years. Jersey has also committed to changing the law to allow assisted dying for the terminally ill.

Australia and New Zealand

In the past few years voluntary assisted dying has become legal across most of Australia. While in New Zealand, patients must be terminally ill and expected to die within six months. That is extended to 12 months for those with a neurodegenerative condition in eligible parts of Australia.

In both countries, patients can self-administer the lethal medication. But it can also be administered by a doctor or nurse, usually via an intravenous injection.

Additional reporting by Anthony Reuben and Gerry Georgieva