'In the midnight sun, slaloming through icebergs' - brothers on perilous Arctic voyage

Brothers Isak and Alex Rockström are navigating through the dangerous Northwest Passage

- Published

“There is no room for error,” says Isak Rockström. “Where we are now, the only help we could get would be from the few Canadian Coast Guard icebreakers that are patrolling the whole Canadian Arctic.”

For the past two months, Isak, 26, and his brother Alex, 25, have been battling the freezing elements of the Arctic Circle together.

They have sailed through the treacherous, sometimes alien landscape of the Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, gathering fresh data about climate change in the region.

They have faced brushes with icebergs and severe gales around Iceland.

One “tricky situation”, as Isak stoically puts it, came the day before they spoke to the BBC. While navigating a fjord, they were caught by 52mph (84kph) winds coming off the nearby mountains, dragging them towards the shore.

“The wind was so strong that with the engine on, we weren’t going anywhere,” he recalls.

Off Devon Island, the largest uninhabited island in the world, they risked running aground due to the area being poorly charted.

They had to quickly turn the other sails so the wind worked in their favour, and “take some things apart and do some jerry-rigging” to get the main sail down, Alex says.

But Isak says “the most challenging ocean crossing of my life” was the long stint around Greenland, through thick fog and ice up the Davis Strait.

He says it felt like they were “trudging on and on... through either gales or fog”.

“Then one day the fog slightly lightened up and there was this little tunnel through the cloud cover in the distance – and we finally actually saw Greenland. And it was just a nice confirmation that we weren’t going crazy.”

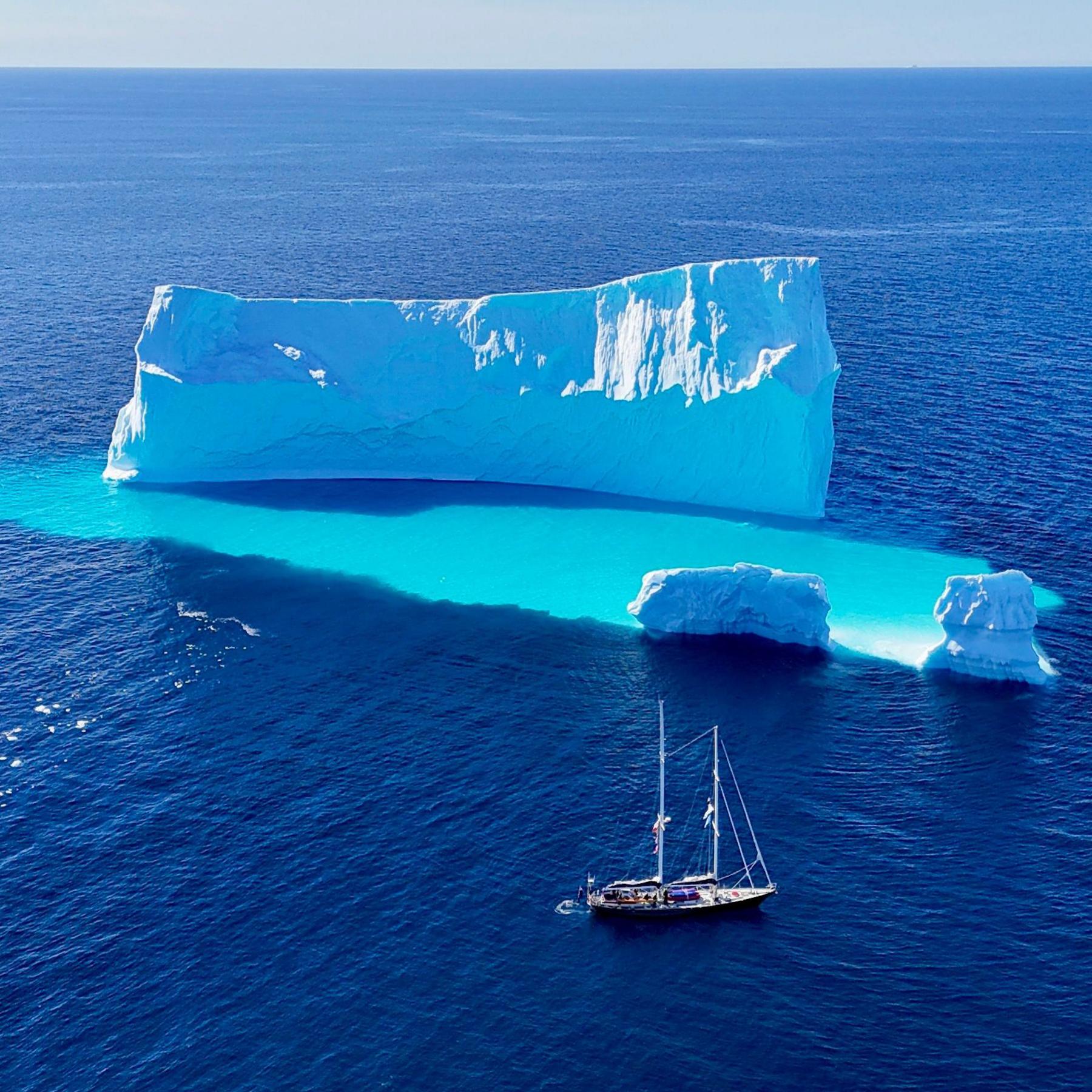

The young brothers are piloting the Abel Tasman, their 75-foot schooner, through icebergs

Free-roaming icebergs near Greenland are spectacular backdrops for the Abel Tasman (pictured) - but make the journey more "unpredictable"

Only a handful of crews successfully navigate this passage every year, and these brothers are among the youngest to ever attempt it.

The BBC is interviewing them part-way through the trip, as they approach one of its most challenging sections – one they are both fearing and anticipating.

Since beginning in Norway in June, the crew of the Abel Tasman have already sailed around Iceland and Greenland, before entering the unaccommodating waters that run between northernmost Canada and the Arctic.

They hope to reach the finishing line in Nome, Alaska by early October.

Skipper Isak is a year older than Canadian Jeff MacInnis was when he completed it in 1988, aged 25. MacInnis is thought to be the youngest person to have successfully sailed the passage.

But they are seasoned sailors – having sailed from Stockholm in Sweden to the western coast of Mexico in 2019.

As captain and first mate, they say piloting their 75-foot schooner has only strengthened their brotherly bond, with their small expedition team serving as an adoptive family.

“I don’t think we’re going to get any closer than we are now,” says Isak.

Alex adds: “I think we really know exactly how the other one works, and we don’t step on each other’s toes.”

Alex says that despite the peril of the journey, he has wanted to traverse the Northwest Passage for a long time. He has been intrigued by maps of the region and tales of previous expeditions, and is aware that it is likely to change due to climate change.

He recalls sailing one night, off the coast of Greenland, that he says will stay with him for the rest of his life.

“We were in the midnight sun, slowly slaloming through huge icebergs, and the light was just incredible when it shone over the icebergs... That was just really beautiful.”

The pair say their current surroundings are "desolate" and "rugged"

Isak took more convincing before making the trip. What persuaded him was that “it’s one of the few expeditions left that really takes on the character of an expedition”, mixing danger and isolation, he says.

Keith Tuffley, the expedition’s overall leader – who quit his job at Citibank to be on the trip and owns the Abel Tasman – has become somewhat of a surrogate father to the Rockströms.

The Rockströms’ real father, Johan, is the Swedish climate scientist who has helped to develop the concept of climate tipping points, when particular large-scale environmental changes are thought to become self-perpetuating and irreversible beyond a certain threshold.

Part of the aim of the expedition is to highlight how climate change is increasing the risks of reaching these tipping points, particularly some systems in the Arctic Circle.

Multiple studies have suggested that parts of the Greenland ice sheet would become much more vulnerable to runaway melting if global warming reached 1.5-2C above pre-industrial levels. However, the precise positions of such tipping points are very uncertain, and a full-scale collapse would likely take many thousands of years.

The Rockströms have lived on the Abel Tasman while studying climate physics at the University of Bergen, balancing their studies with expeditions.

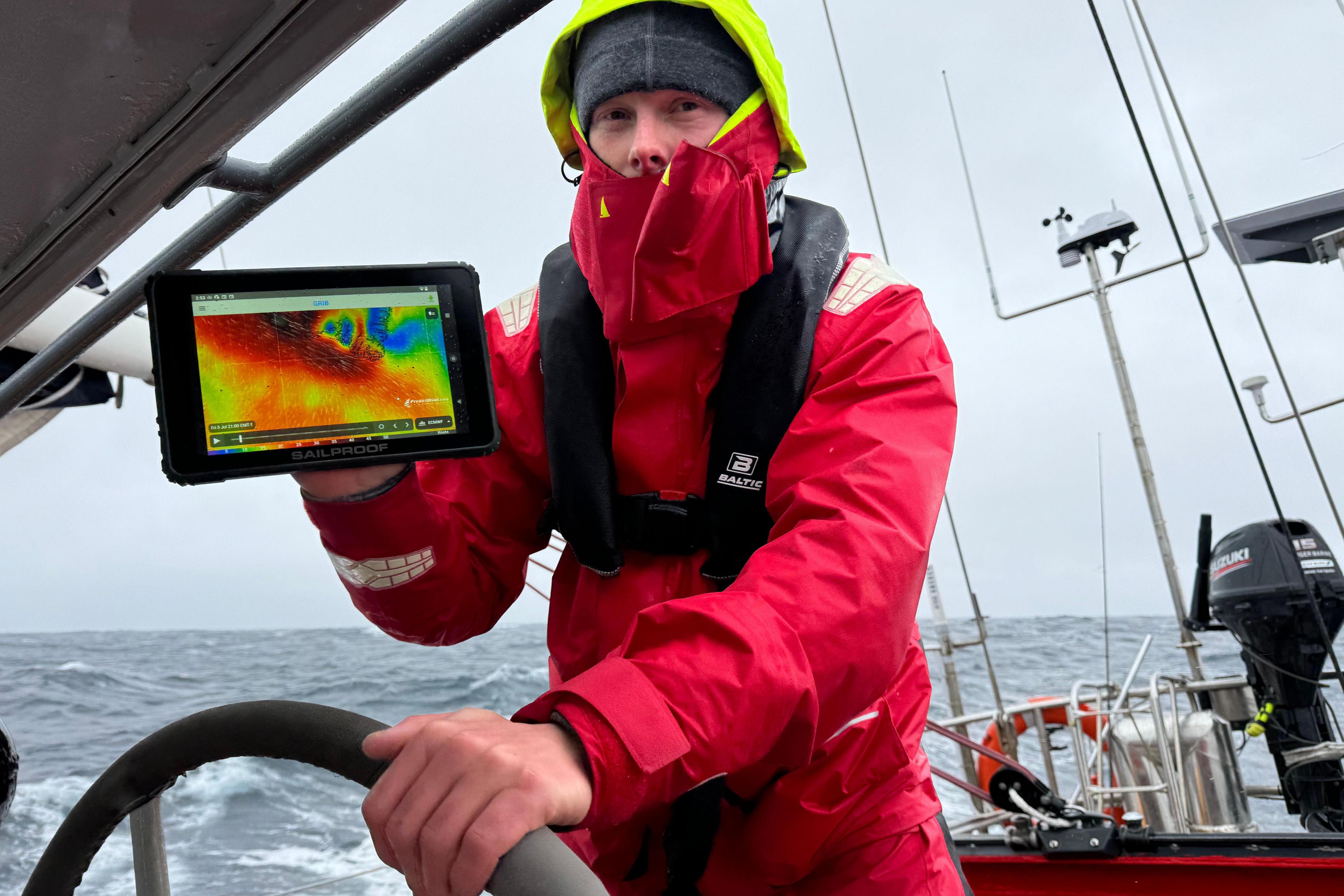

While much of the data they are gathering will have to be sent back to laboratories for analysis, Alex says the raw figures from seawater measurements they have already taken suggest the waters around Greenland are colder and less salty than before – a sign of ice sheet melting.

Sailing around Greenland felt like "trudging on and on... through either gales or fog"

The Rockströms are among the youngest to take on sailing the Northwest Passage

Prof David Thornalley, an ocean and climate scientist at University College London, explains that, over time, the influx of freshwater flowing off the Greenland ice sheet is likely to weaken the main current that runs the length of the Atlantic and has a major influence on the climate.

The melting of the ice sheet also raises global sea levels, increasing the risks of coastal flooding.

As well as potentially affecting the balance of the marine ecosystem, Prof Thornalley says melting ice might also produce a feedback process, “whereby the meltwater causes the ocean circulation changes, which leads to warmer waters reaching glaciers that flow into the ocean, thus causing faster melting and retreat of the glacier”.

Alex hopes the data they gather along the Northwest Passage will be significant.

“I think it's very easy to underestimate the value of the data that can be collected from a sailing yacht like this... The big ships, the big icebreakers, are so limited in where they can go.”

Their current surroundings "look like Mars", says expedition leader Keith

The crew of the Abel Tasman still have a long and challenging way to go.

“Where we are now is one of those points along the trip that, from day one, we’re kind of fearing and very hopefully anticipating, because it’s... the start of the really challenging part,” says Isak.

Tuffley, the expedition’s leader, says that while melting Arctic ice was making it easier for a boat to move through the Northwest Passage, the icebergs this process was creating were making the journey more “unpredictable”.

At times, their surroundings appear completely alien.

“It looks like Mars,” says Keith of where they are anchored, in Devon Island.

“It is desolate, it’s rugged. It’s got this red, iron ore type of tinge to it.”

Aside from a handful of walruses and polar bears, the crew are entirely alone.

Related topics

- Published17 October 2023

- Published18 June 2024

- Published6 March 2024