'I need to find my missing children and grandchildren'

Emad Al Rawashdeh was resettled to Omagh in 2018 after fleeing the war in Syria

- Published

The search for a family missing for over a year has been fuelled by an extraordinary friendship between an Omagh bomb victim and a Syrian refugee.

Similar traumas have forged a bond between Michael Gallagher, whose son Aiden was killed in the 1998 Real IRA attack, and Emad Al Rawashdeh.

Mr Gallagher is supporting Mr Al Rawashdeh in his hunt for his two children and five grandchildren who have been missing since August 2024.

Mr Al Rawashdeh, who now lives in Omagh, returned to Syria earlier this month to look for his family.

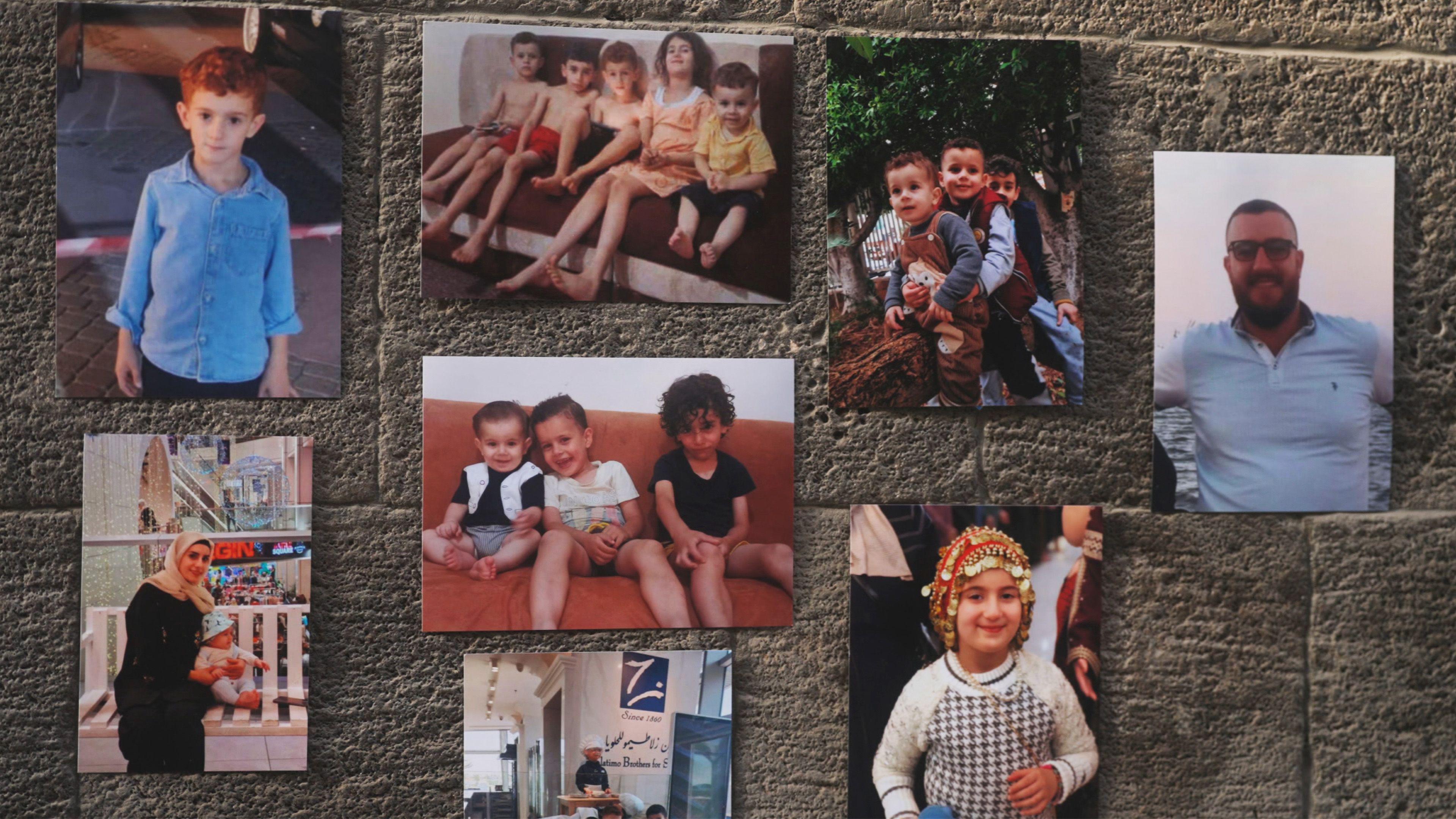

Pictures of Emad's missing family members were shared with support organisations in Syria

He was followed by BBC News NI's Spotlight team.

"Everybody has some pain in their life. People say move on. You don't move on," Mr Gallagher said.

"You just learn to manage that pain a lot better than what you did.

"I just feel for Emad's family, for the pain and the suffering that we can't see."

Mr Al Rawashdeh met Mr Gallagher after he and part of his family were resettled into Omagh by the United Nations in 2018 after fleeing the Syrian civil war.

Family members who remained in the Middle East tried to flee last year by making contact with human traffickers in Libya.

Emad last heard from the group in August 2024 - he said his son explained they were in touch with a trafficker who would help them reach Italy by boat.

Emad, who travelled to Libya last year on a similar trip, said he will "never stop" looking for his missing family.

Michael Gallagher (left) and Emad Al Rawashdeh (right) want answers over what happened to their children

What happened in Syria?

Waad Al Rawashda travelled to Northern Ireland with her father and other members of the family

A peaceful uprising against the president of Syria in 2011 turned into a full-scale civil war.

The conflict left 500,000 dead, and displaced about six million others.

Before the conflict, many Syrians were complaining about high unemployment, corruption and a lack of political freedom under President Bashar al-Assad, who succeeded his father, Hafez, after he died in 2000.

In March 2011, pro-democracy demonstrations erupted in the southern city of Daraa, inspired by uprisings in neighbouring countries against repressive rulers.

Strikes left widespread damage to buildings and infrastructure in many parts of Syria

When the Syrian government used deadly force to crush the dissent, protests demanding the president's resignation erupted nationwide.

Opposition supporters took up arms and the country descended into civil war.

Last year, Bashar al-Assad ordered a crackdown on pro-democracy protests but that was met with an offensive led by the Islamist militant group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

It took 12 days for Assad's military to collapse and he stepped down as Syria's president.

The new Syrian flag, known as the "independence flag", overlooks the capital, Damascus

How did Emad's family get separated?

In 2014, the Al Rawashdeh family fled their home just outside Daraa, the birthplace of the revolt in Syria, and went to Lebanon.

Their home had been hit by a bomb and engulfed in flames.

Four years later, the United Nations resettled Emad and some of his family to the town of Omagh in County Tyrone.

However, his eldest son Hassn, and a daughter, Haneen, were not among those airlifted out of Lebanon in 2018.

Emad says he will not return to live in Syria because too much has changed

August 25th, 2024 was the last time the rest of the family in Omagh heard from them.

In a hurried voice message, Hassn said that they were being moved that evening.

"We're on our way by car, heading to our location, God willing," he was heard saying in a translated message.

Given the risk of drowning during the crossing or of detention by Libyan authorities, it's a journey many take out of desperation.

Syria to Omagh: Lost & Missing

Tied by trauma – a father searching for his vanished family and another whose only son died in the Omagh bombing.

Watch now on iPlayer or on Tuesday 21 October at 22.40 on BBC One Northern Ireland.

"The problem, specifically with Libya, is that there are a lot of smugglers making profit out of despair," said Eleonora Servino, Chief of Mission from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Syria.

"For a Syrian, this means that maybe you go there and say 'I can just find a job, stay here,' or you just feel that you are so close to Europe that you're just one step away to join your family. But, the journey is very dangerous."

Eleonora Servino, from the International Organization for Migration, says smugglers are making profit from despair

Five children are among the group who have now been missing for more than a year.

Now carrying a British passport, Emad returned to Syria earlier this month in an effort to try to secure official help to find the missing.

BBC Spotlight observed his journey for answers in Syria, a country still on the fringes of a fragile peace.

Some areas continue to have armed militia patrols on empty streets, while in other locations the BBC crew was ordered to leave, escorted by armed guards, due to the security threats posed.

BBC Spotlight reporter Jennifer O'Leary travelled to Syria earlier this month

Emad, who says he will not return to live in Syria, is desperate for answers.

"Some people, people that would tell me 'all the family died. The fish ate your kids'," he said.

His pain is compounded by grief for a son killed in a motorcycle accident in Lebanon and two brothers killed during the civil war.

The distress for missing loved ones is a pain felt by tens of thousands of families across Emad's homeland where some 100,000 people have been missing since 2011.

Emad will not enter his former home, near Daraa, until he knows what happened to his family

In Damascus, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC), one of the organisations operating a family tracing system, met Emad to gather more information about his family.

"Some of the families have missing [relatives] from the armed conflict, some from migration, so the problem is really mixed and complicated for all the families," explains Dr Muhammad Sukar from SARC.

"Our goal in the end is to get the fate and whereabouts of the missing.

"What we are talking about is the fate – if they are dead or alive".

In a statement to the BBC, the Libyan Embassy in Damascus also confirmed they were aware of Emad's case, and confirmed they would provide humanitarian and consular assistance to him and his family.

Emad met several organisations helping to locate the missing, including the Syrian Arab Red Crescent

'Pain and suffering we can't see'

In Omagh, the Al Rawashdehs are attempting to rebuild their lives.

Emad's bond with Michael Gallagher was forged by their common search for answers about what happened to their children.

Mr Gallagher, who is hoping for answers through a long-awaited public inquiry into the Omagh bombing, has spent decades seeking information about his own son's death.

"I had to know what went wrong," he said.

"And, I think Emad needs to know, is his family dead or alive? And, if they are dead, where are they?"

Both fathers, who are victims of separate conflicts, have promised to support each other in seeking answers over what has happened to their loved ones.

- Published14 March

- Published9 December 2024