Why the legacy of Storm Amy may harm Scotland's native fish

Environmentalists have long raised concerns about the impact of farmed salmon on wild fish

- Published

Storm Amy, the first named storm of the season, left damaged power lines, downed trees and frustrated travellers in its wake earlier this month, but its biggest long term impact will almost certainly be on fish.

As the final homes were getting their power reconnected, fish farm operator Mowi made an unexpected announcement - about 75,000 salmon had escaped from a damaged enclosure in the Scottish Highlands.

The rough seas and high winds had torn the netting at a pen at the Gorsten farm on Loch Linnhe, a sea loch in Lochaber.

At first sight it might look like a lucky break for fish that might otherwise end up on supermarket shelves - but marine scientists and conservationists are worried.

What's the problem with fish farm escapes?

Scottish wild salmon begin their lives in Scottish rivers where they live for several years before turning into "smolts" and beginning their migration to the sea.

After one to three years in the North Atlantic, they make an epic journey back to the river where they born in order to spawn.

The majority of adults then die although some head back out to sea.

The big danger is that the farmed salmon escapees will inter-breed with wild salmon, changing the genetic make-up of the next generation of fish.

The salmon raised in pens in Scotland's lochs are often Norwegian strains of the species

Dr Will Perry from Cardiff University, an expert on freshwater eco-systems, said most salmon bred by the fish farming industry in Scottish waters are from Norwegian strains.

"They are selected for growth, they are selected for all the things that are of commercial importance, so when they are in this wild environment they are maladapted," he explained.

"They've got these maladapted genes that are passed on to the wild gene pool where you get this hybridisation."

That's not the only concern.

They can also also spread diseases and parasites, like sea lice, to vulnerable wild populations and compete with native fish for food, adding to pressure on already endangered Scottish Atlantic salmon.

Will the farmed salmon survive in the wild?

The good news (although not for the escapees) is that most of them will die fairly quickly.

They have been genetically selected for the farmed environment and are not well equipped to deal with the rigours of life in the North Atlantic.

But the sheer size of the latest outbreak means some of them will survive.

Low level "leakage" is common but the last release on this scale was in February 2023 when 80,000 smolts escaped through an unsecured hatch, external while being transported from Loch Shin - and that was the biggest escape in a decade.

To put that into perspective, it's believed only about 300-400,000 Scottish wild salmon return to the coast each year to spawn, external, so the Loch Linnhe escapees are equivalent to about a fifth of the entire returning population.

Salmon can sometimes be seen leaping over small waterfalls as they journey back ot the place of their birth

The unanswered question is how many will join the migration back up Scottish rivers - which at this time of year is already under way - providing the spectacle of the salmon run with fish leaping out of the water to pass small waterfalls.

Dr Perry said: "You will get a small proportion that do survive and beat the odds and get through the mortality - and they will return to salmon rivers."

He added past research had found upwards of 1% - and in extreme cases up to 10% - of salmon in Scottish rivers were escapees.

It's also unclear whether they will just tag along for the ride, or whether they will then breed with native Scottish salmon when the spawning season begins in November. Again, the evidence suggests some of them will.

Research for Marine Scotland published in 2021 looked at more than 250 sites and found signs of "introgression" , external- the transfer of genetic material - in 55 of them while at 14 locations "major genetic changes" were detected.

And that could introduce genetic weaknesses into a native population already classified as endangered in Britain,, external having declined by 30-50% since 2006.

What can be done about it?

Campaigners are calling for stronger incentives for fish farms to do more to prevent escapes.

Some countries like Norway and Chile - which had some very large fish farm escapes in the past - now impose big fines and heavy regulation on operators.

In Scotland there are currently no financial penalties for escapes, just enforcement notices which only incur a fine if no action is taken.

The system also relies on self-reporting which some believe underestimates the scale of the problem.

Seven years ago a Scottish Parliament committee called for a system of penalties and Scottish ministers have promised to act.

But in a recent update on progress, external they said a penalty system won't be introduced until 2026/27.

A penalty system for escapes of farmed salmon in Scotland could be some years away

Scottish Greens MSP Ariane Burgess, a member of Holyrood's rural affairs committee, believes there's a lack of urgency from government at regulating an industry that's become "out of control" .

She said: "In 20 years time, we'll look back and ask ourselves 'why did we let this happen?'"

The Scottish government said it remained committed to introducing a penalty system and it expected firms to minimise escapes in the meantime.

A spokesperson added: "The risks of introgression associated with this escape are likely to be relatively low as the fish are unlikely to mature this year and are unlikely to survive to breed in substantial numbers in subsequent years."

A catch and return drive on Scottish rivers where the fish spawn has helped slow the decline

Fish farm escapes aren't the only threat to Scotland's native salmon.

Many believe global warming is one of the main factors in population decline because the fish are so sensitive to temperature changes.

Another non-native species, pink salmon which were introduced into Russian rivers in the 1960s, have simply strayed into Scottish waters.

But despite the challenges, there as been some progress in conservation which has slowed the decline.

While the numbers of fish returning to Scotland's coasts each year have fallen from about a million in the 1970s to less that half that figure, the numbers going on to spawn have remained relatively stable, at least until recently.

That's because of a mix of voluntary and legal measures that have reduced the number of fish killed once they reach the rivers.

Any salmon caught before 1 April must be released again - and after that it depends on the conservation status of the river.

What does the salmon industry say

Salmon farming is a major export for Scotland, which the industry body said contributes more than £760m to the economy, external when you include the supply chain.

According to Salmon Scotland, it provides direct employment for more than 2,500 people and 10,000 in indirect roles across Scotland.

The mass production techniques of fish farms have transformed salmon from a delicacy once only enjoyed by the rich to a healthy food enjoyed by millions.

Operators said the causes of escapes can range from extreme weather, technical failure when transferring fish or a seal biting through the netting.

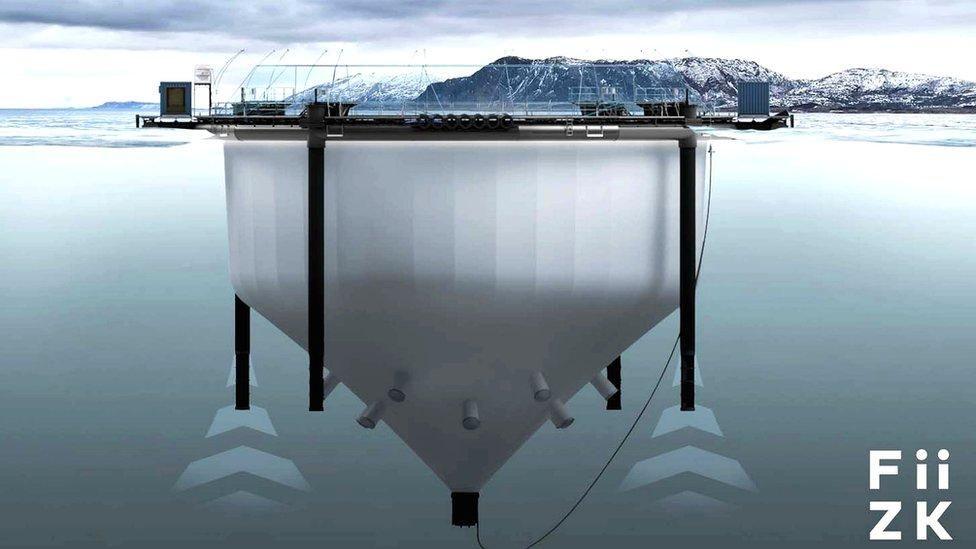

And they insist they are taking action to reduce the problem, investing in training, stronger netting, pen design and mooring technology.

Mowi, the operator of the farm where the latest escape took place, said an initial investigation had found Storm Amy caused mooring anchors to drag and the netting was then torn when it came into contact with a pipe.

The Norwegian firm said its staff have to complete mandatory training each year, external on preventing escapes, and it is investing in more robust equipment.

A statement added: "Mowi has set a target of zero escapes and invests in people and equipment to achieve this."

Related topics

- Published17 January

- Published29 May

- Published27 August