For years, a people smuggler known as Scorpion is believed to have controlled the trade across the English Channel. And yet he remained a free man.

Unable to track him down, a Belgian court convicted him in his absence of 121 counts of people-smuggling. We found him living openly in Iraqi Kurdistan, where he admitted to us that he had illegally transported thousands of migrants across the channel.

Barzan Majeed - his real name - was arrested by local police days after the release of our podcast. After the news broke, the question we asked again and again, was why was it easy for us to find him, but so hard for the police?

The answer is that police forces in different countries struggle to co-operate, but Majeed’s arrest has raised hopes that more co-operation could follow - along with more arrests.

Majeed had been the subject of a joint UK-Belgian investigation before he was tried in absentia, and a senior Kurdish government source told us that British police had been invited to Iraq to question him.

European investigators have given Iraqi officials the names of other high-level smugglers convicted in their absence, says Ann Lukowiak, the Belgian public prosecutor who helped compile the case against Majeed.

“We hope that other cases will follow,” she said, adding that Majeed’s arrest sent a clear message to smugglers that they would be “found and taken down”.

The arrest has sent shockwaves through the smuggling world, according to Rob Lawrie - a former soldier who works with refugees and co-presented the BBC investigation.

In WhatsApp messages, one smuggler told Lawrie that he had considered himself untouchable until Majeed’s arrest.

“It is making us nervous for the simple reason that we felt safe here in north Iraq,” the smuggler said. “We haven’t been stopped by police before, no-one has been arrested here for this. All of us know Barzan was arrested, and everyone is talking about it.”

BBC journalist, Sue Mitchell, and volunteer aid worker, Rob Lawrie go on a dramatic hunt for one of Europe's most-wanted crime bosses. Code-named Scorpion, he's smuggled thousands of people into the UK and is on the run.

Police and prosecutors who thanked the BBC for securing Majeed’s arrest told us they simply did not have the ability to investigate in the same way that reporters could.

“For journalists, it’s easier to track him down because there is no formal procedure they have to follow,” said Mrs Lukowiak. “(The BBC journalists) moved from one source to another, from one city to another, from one country to another, in a way that police and prosecutors can’t.”

A spokesman for the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA) agreed. “We are a government law enforcement agency, there are legal processes we rightly have to abide to, that the media do not, and Majeed was in a location where we have no jurisdiction.”

He said the NCA engaged closely with the BBC during its investigation, briefing reporters on its own inquiries into Majeed.

Chris Philp, the UK policing minister, said the BBC’s journalism did nothing to detract from the work going on at the NCA to identify and arrest people smugglers.

The NCA was working with colleagues in Turkey to stop huge numbers of boats from there sailing to Europe, he said. “They are working right across the whole supply chain.”

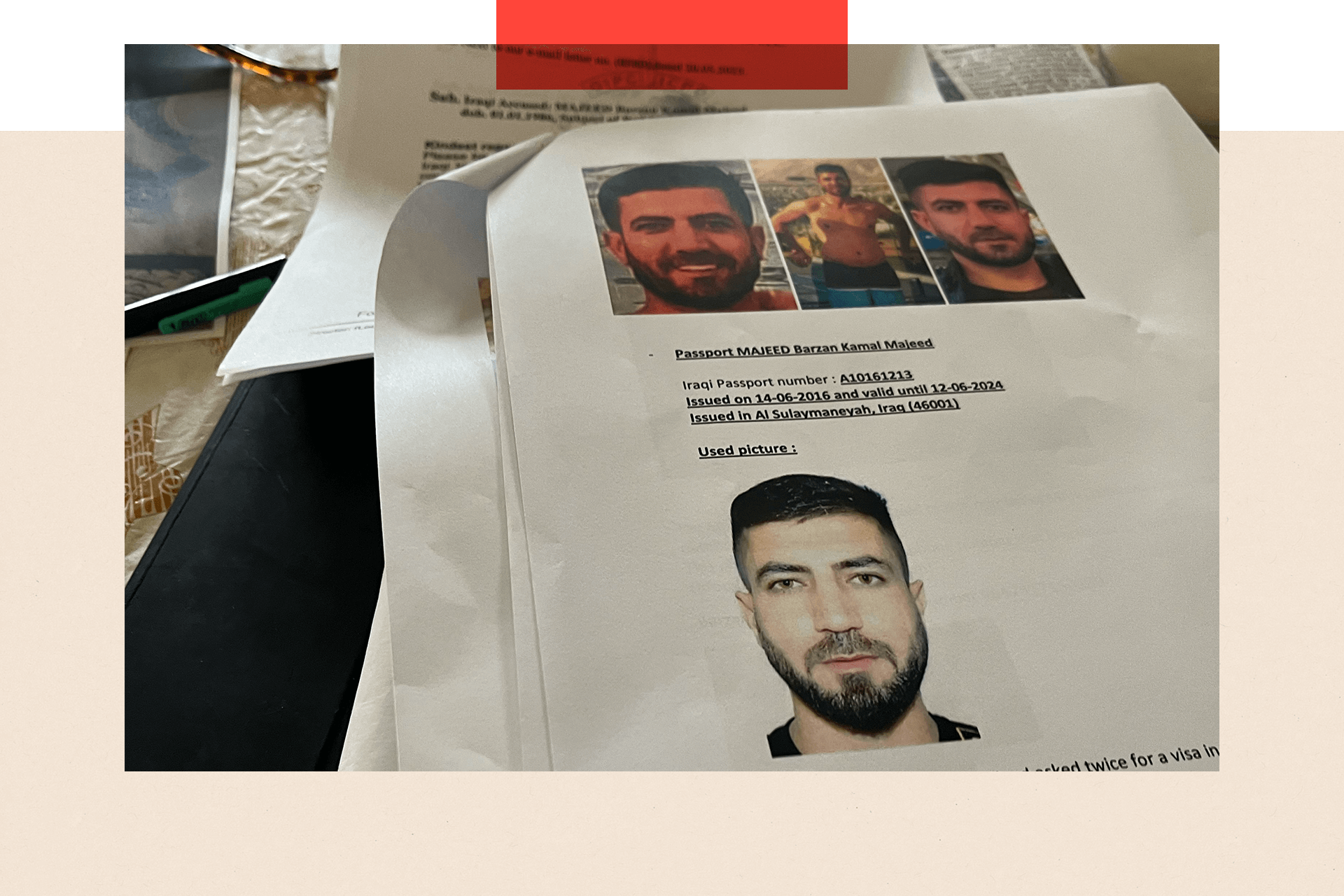

A police document shows Majeed's mugshot

Britain and Turkey issued a joint statement last year pledging to enhance co-operation in the fight against smuggling gangs. As part of this, Turkey agreed to set up a new centre of excellence to strengthen collaboration and increase intelligence-sharing between enforcement agencies.

But Mrs Lukowiak says she not seen much progress on the ground. “We have seen evidence of Turkish police just looking on when migrant boats are setting off from the coast there,” she says. “We see the same thing in France, with police looking on at boats leaving.” French police say they only intervene when it is safe to do so.

The Home Office said it did not comment on operational matters, and we’re still waiting for a reply from the Turkish government.

Part of the problem is that co-operation agreements have to be drawn up on a country-by-country basis. It is slow, painstaking work, especially when dealing with countries like Iran, Cambodia and Vietnam, for example. Criminal gangs can exploit these weaknesses in international legal frameworks.

Mrs Lukowiak says efforts to get counties to work together are improving, but bureaucracy remains an obstacle.

Vassilis Kerasiotis, a human rights lawyer in Greece who has defended low-level smugglers, said criminals at the top know how to exploit the system and stay hidden from the authorities.

"Governments do not ask the really central questions about how we can really make things safer and what we can do across borders to properly police this trade,” he said.

More from InDepth

Putin and Xi no longer have a partnership of equals

- Published17 May 2024

Is the move to electric cars running out of power?

- Published17 May 2024

Laura Kuenssberg: How it went wrong for Project Sunak

- Published15 May 2024

This was echoed by Mrs Lukowiak, who said her team had recently uncovered evidence of a well-organised smuggling ring based in Athens.

The men at the centre of this criminal gang were supplying false documents at a cost of around £5,000 a time and there was evidence that they were responsible for thousands of migrant journeys across Europe. Yet she says she could not get Greece to co-operate with her in arresting the gang’s leaders.

“We extracted two people as they were in Belgium, but the rest of the gang is still operating,” she says. “They have just set up elsewhere.”

A Greek police spokeswoman said she could not comment on an ongoing investigation but that they liaise with other police forces and seek to co-operate on cross-border investigations whenever possible.

The deputy prime minister of the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq, Qubad Talabani, said that Majeed’s arrest was a sign that progress had been made on international co-operation, but he felt there had not been enough discussion about how to prevent these cases from occurring in the first place.

Poverty and economic hopelessness had been the main drivers behind the traffic, he said. More recently, as a result of deaths during crossings, he said parents in Iraq did not want their children to risk going on these dangerous journeys.

“An injection of money and support [to improve the economic opportunities in areas people are illegally migrating from] could really turn this tide. That is a much more strategic way of dealing with the problem.”

There may have been a gradual awakening about the scale of the effort needed to tackle the people-smugglers, but the dangerous trade in human lives continues.

While the arrest of Majeed was a significant landmark, he remains for now an exception.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.