Scottish government reveals plan to reach net zero targets by 2045

- Published

The Scottish government has announced its strategy to move towards net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.

A draft climate action plan includes targets to decarbonise building heat systems, phase out new petrol and diesel cars by 2030, increase woodland planting and accelerate peatland restoration.

Climate Action Secretary Gillian Martin told MSPs that Scotland was already being affected by flooding, heatwaves and wildfires, and that parliament had to act.

Opposition MSPs, however, accused ministers of regurgitating old ideas and providing a lack of detail.

Hedgerows and mob grazing: Can farming fix its carbon black hole?

- Published4 days ago

Renewables jobs not making up for North Sea decline, MPs warn

- Published24 October

The draft plan, which will face further scrutiny from parliament, sets out the government's strategy until 2040 - five years before Holyrood ministers say they will effectively eliminate greenhouse gases.

The strategy recommits Scotland to phasing out new diesel and petrol cars by 2030, and sets the target of "decarbonising" heating in buildings by 2045, which would include a switch away from gas boilers or systems using oil.

Non-domestic buildings will be required to connect to low-carbon district heating systems, which are to be extended.

The plan proposes increasing Scotland's woodlands, so that by 2029-30 18,000 hectares are planted a year.

The strategy also includes consumer incentives to encourage drivers to switch to electric vehicles.

The government proposes more investment in peatland restoration to offset a pledge to farmers that livestock numbers will not have to be cut. That is to be combined with faster decarbonisation in fuel supply.

The Climate Change Committee had advised that cattle numbers would need to be cut to achieve reductions in agriculture, which is the third biggest source of planet-warming emissions.

The combined climate policies will cost £4.8bn between 2026 to 2040, but bring benefits of £42.3bn, according to the government.

Martin, who announced the strategy in parliament, pointed to "massive untapped potential" in renewable energy, but also said there was a particular responsibility to support oil and gas workers with a "just transition".

Climate Action Secretary Gillian Martin announced the new climate plan

Scottish Conservative energy spokesman Douglas Lumsden said that the plan "rehashes existing SNP policies which do nothing to bring down energy bills and provide no clarity on how they intend to reach the 2045 target".

He said it failed to address concerns about moves to replace household boilers with heat pumps, trading in petrol vehicles for electric alternatives and a presumption against new oil and gas exploration.

Labour's Sarah Boyack said more detailed plans were needed on how to retrofit homes to improve energy efficiency and warned there was a lack of support for local authorities to create jobs in green industries and invest in homes.

Green MSP Patrick Harvie said Scotland was "years behind where it should be on climate".

He accused ministers of slowing down environmental action and rejecting the "clear advice" of the Climate Change Committee on agriculture.

"They give no clarity at all on fossil fuel extraction and they've filleted the heat and buildings bill, now proposing a target with no delivery mechanism," Harvie added.

Liberal Democrat MSP Willie Rennie welcomed some aspects of the plan but added that there was little new information in the draft proposals.

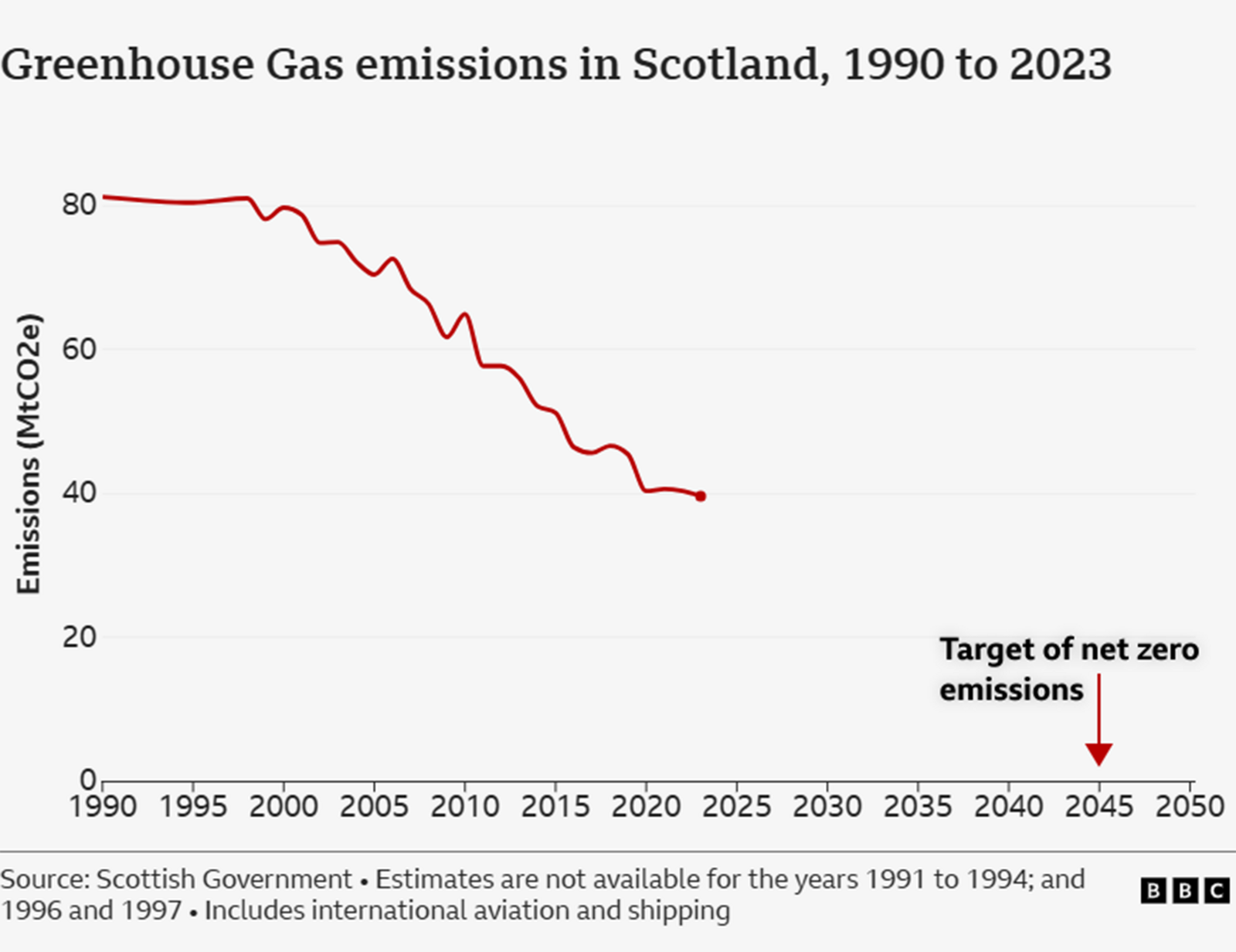

The Scottish government has pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2045 - five years earlier than the UK government's target date of 2050.

But after repeatedly missing annual and interim targets, SNP ministers abandoned them last year in favour of five-yearly carbon budgets.

The government is aiming to cut emissions by an average of 57% over the next five years and by 69% by 2035, when compared with 1990 levels. By 2040, ministers hope to increase that figure to 80%.

The most recent data, external, from 2023, shows that planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions in Scotland were down by more than 50% against the 1990 baseline year.

The publication of the draft climate change plan has been delayed since November 2023, when ministers said they had to postpone the release due to a change in the UK government's net zero commitments.

Opposition MSPs say the plan lacks details about the phase out of oil and gas energy sources

The Scottish government said it was committed to transitioning away from fossil fuels to greener sources of energy, though First Minister John Swinney has said North Sea oil and gas would be needed "for a period of time".

The licensing of offshore oil and gas fields for exploration or extraction is reserved to the UK government.

Labour ministers have committed to banning new exploration licences, though this would not rule out developing existing fields.

The draft plan is out for consultation until 29 January. Responses will be considered before the final plan is rubber-stamped.

Think tank IPPR Scotland said that the government had made a "positive case" for climate action but that "key questions appear to remain unanswered".

Friends of the Earth Scotland head of campaigns Caroline Rance said the "dreadful plan" would "barely scratch the surface" of what was required.

She added: "There is nothing here to help people who are struggling to pay their energy bills, communities cut off by unreliable buses, or oil workers worried about their future."

The devil is in the detail. And there is a lot of it in the draft climate plan. Hundreds of pages, in fact.

But what jumps out is what ministers clearly state are their alternatives to cutting livestock numbers.

Agriculture is the third biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions and yet the first minister promised that herd sizes would stay the same.

Firstly, restoring more of Scotland's peatlands which - in poor condition, as most are - are notoriously leaky on the carbon front.

By 2032, it is promised that one fifth of those peatlands - 400,000 hectares - will be restored although working out a way to do that without pumping endless amounts of public money at it has long proved tricky.

That pledge is coupled with a commitment towards "higher fuel supply decarbonisation" which essentially means importing fewer fossil fuels and increasing our capacity of wind and solar energy.

That is happening anyway and depends largely on whether we are able to wean ourselves off oil and gas by reducing demand.

The overall net cost is an eyewatering £4.8bn over 15 years but Martin says there are other benefits like job creation and warmer homes.

But there is a culture war going on over the net-zero agenda and while there may be a rare point of unity between the SNP at Holyrood and Labour at Westminster over its importance, pressure from Reform and the Conservatives means delivering this plan will not be as easy as it once was.

Scotcast: Climate change and the culture wars

The BBC’s Kevin Keane tells us what Scottish Government route map could mean for you.

Related topics

- Published29 October

- Published2 days ago

- Published3 days ago