Coffee price surges to highest on record

- Published

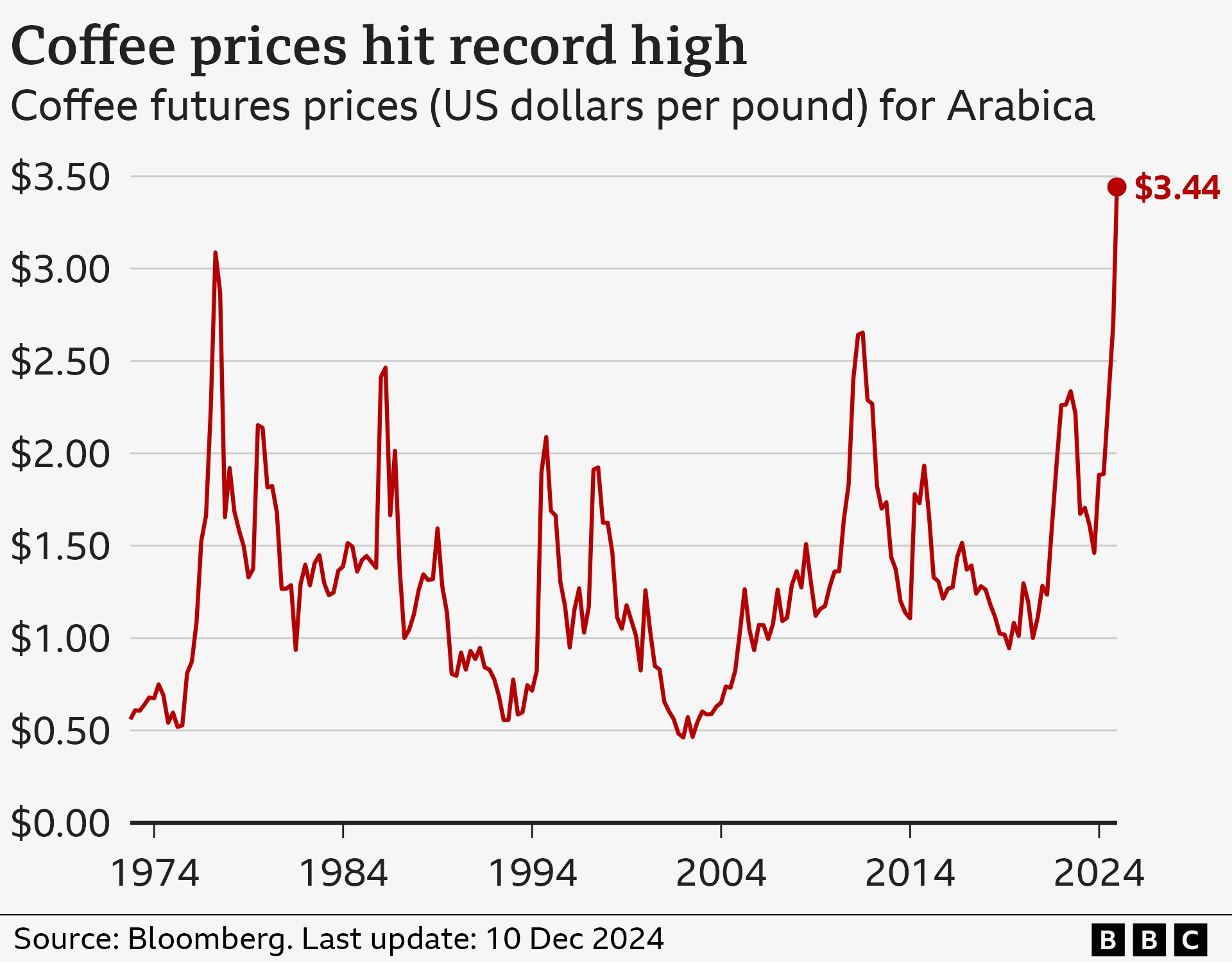

Coffee drinkers may soon see their morning treat get more expensive, as the price of coffee on international commodity markets has hit its highest level on record.

On Tuesday, the price for Arabica beans, which account for most global production, topped $3.44 a pound (0.45kg), having jumped more than 80% this year. The cost of Robusta beans, meanwhile, hit a fresh high in September.

It comes as coffee traders expect crops to shrink after the world's two largest producers, Brazil and Vietnam, were hit by bad weather and the drink's popularity continues to grow.

One expert told the BBC coffee brands were considering putting prices up in the new year.

While in recent years major coffee roasters have been able to absorb price hikes to keep customers happy and maintain market share, it looks like that's about to change, according to Vinh Nguyen, the chief executive of Tuan Loc Commodities.

"Brands like JDE Peet (the owner of the Douwe Egberts brand), Nestlé and all that, have [previously] taken the hit from higher raw material prices to themselves," he said.

"But right now they are almost at a tipping point. A lot of them are mulling a price increase in supermarkets in [the first quarter] of 2025."

Italian coffee giant Lavazza said it had gone to great lengths to protect its market share and not pass on higher raw material costs to customers, but soaring coffee prices had eventually forced its hand.

"Quality is paramount for us and has always been the cornerstone of our contract of trust with consumers," the company told BBC News.

"For us, this means continuing to tackle very high costs. So we have been forced to adjust prices."

At an event for investors in November, a top Nestlé executive said the coffee industry was facing "tough times", admitting his company would have to adjust its prices and pack sizes.

"We are not immune to the price of coffee, far from it," said David Rennie, Nestlé's head of coffee brands.

Drought and heavy rain

The last record high for coffee was set in 1977 after unusual snowfall devastated plantations in Brazil.

"Concerns over the 2025 crop in Brazil are the main driver," said Ole Hansen, head of commodity strategy at Saxo Bank.

"The country experienced its worst drought in 70 years during August and September, followed by heavy rains in October, raising fears that the flowering crop could fail."

It is not just Brazilian coffee plantations, which mostly produce Arabica beans, that have been hurt by bad weather.

Robusta supplies are also set to shrink after plantations in Vietnam, the largest producer of that variety, also faced both drought and heavy rainfall.

Coffee is the world's second most traded commodity by volume, after crude oil, and its popularity is increasing. For example, consumption in China has more than doubled in the last decade.

"Demand for the commodity remains high, while inventories held by producers and roasters are reported to be at low levels," said Fernanda Okada, a coffee pricing analyst at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

"The upward trend in coffee prices is expected to persist for some time," she added.