'A tech firm stole our voices - then cloned and sold them'

Paul Skye Lehrman and Linnea Sage have filed a class action lawsuit against Lovo

- Published

The notion that artificial intelligence could one day take our jobs is a message many of us will have heard in recent years.

But, for Paul Skye Lehrman, that warning has been particularly personal, chilling and unexpected: he heard his own voice deliver it.

In June 2023, Paul and his partner Linnea Sage were driving near their home in New York City, listening to a podcast about the ongoing strikes in Hollywood and how artificial intelligence (AI) could affect the industry.

The episode was of interest because the couple are voice-over performers and - like many other creatives - fear that human-sounding voice generators could soon be used to replace them.

This particular podcast had a unique hook – they interviewed an AI-powered chat bot, equipped with text-to-speech software, to ask how it thought the use of AI would affect jobs in Hollywood.

But, when it spoke, it sounded just like Mr Lehrman.

"We needed to pull the car over," he said.

"The irony that AI is coming for the entertainment industry, and here is my voice talking about the potential destruction of the industry, was really quite shocking."

That night they spent hours online, searching for clues until they came across the site of text-to-speech platform Lovo. Once there, Ms Sage said she found a copy of her voice as well.

"I was stunned," she said. "I couldn't believe it."

"A tech company stole our voices, made AI clones of them, and sold them possibly hundreds of thousands of times."

They have now filed a lawsuit against Lovo. The firm has not yet responded to that or the BBC's requests for comment.

Clone wars

But how was Lovo able to recreate their voices? The couple alleges it was done under false pretences.

Lovo co-founder Tom Lee has previously said its voice-cloning software only needs a user to read about 50 sentences to create a faithful clone.

"We can capture the tone, the character, the style, the phonemes, and even if you have an accent, we can capture that as well," he told the Future Visionaries podcast in 2021.

In their lawsuit, the couple set out how they say Lovo obtained just such a recording from them.

They allege anonymous Lovo employees contacted them to record audio assets on Fiverr, the popular freelance talent website, where they were selling their services to provide audio for television, radio, video games, and other media.

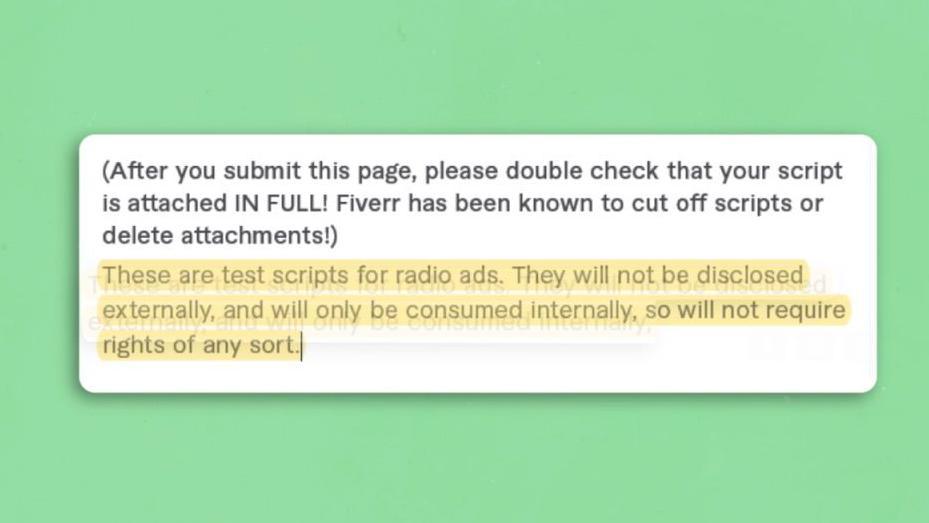

First, in 2019, Ms Sage says a user reached out asking for her to record dozens of generic sounding test radio scripts.

Test recordings are often used in film and television for focus groups, internal meetings, or as placeholders for works in progress. Because they won’t be shared broadly, these recordings cost much less than audio meant for broadcast.

Ms Sage says she completed the job, delivered the files, and was paid $400 (£303).

About six months later, Mr Lehrman says he got a similar request to record dozens of generic sounding radio ads.

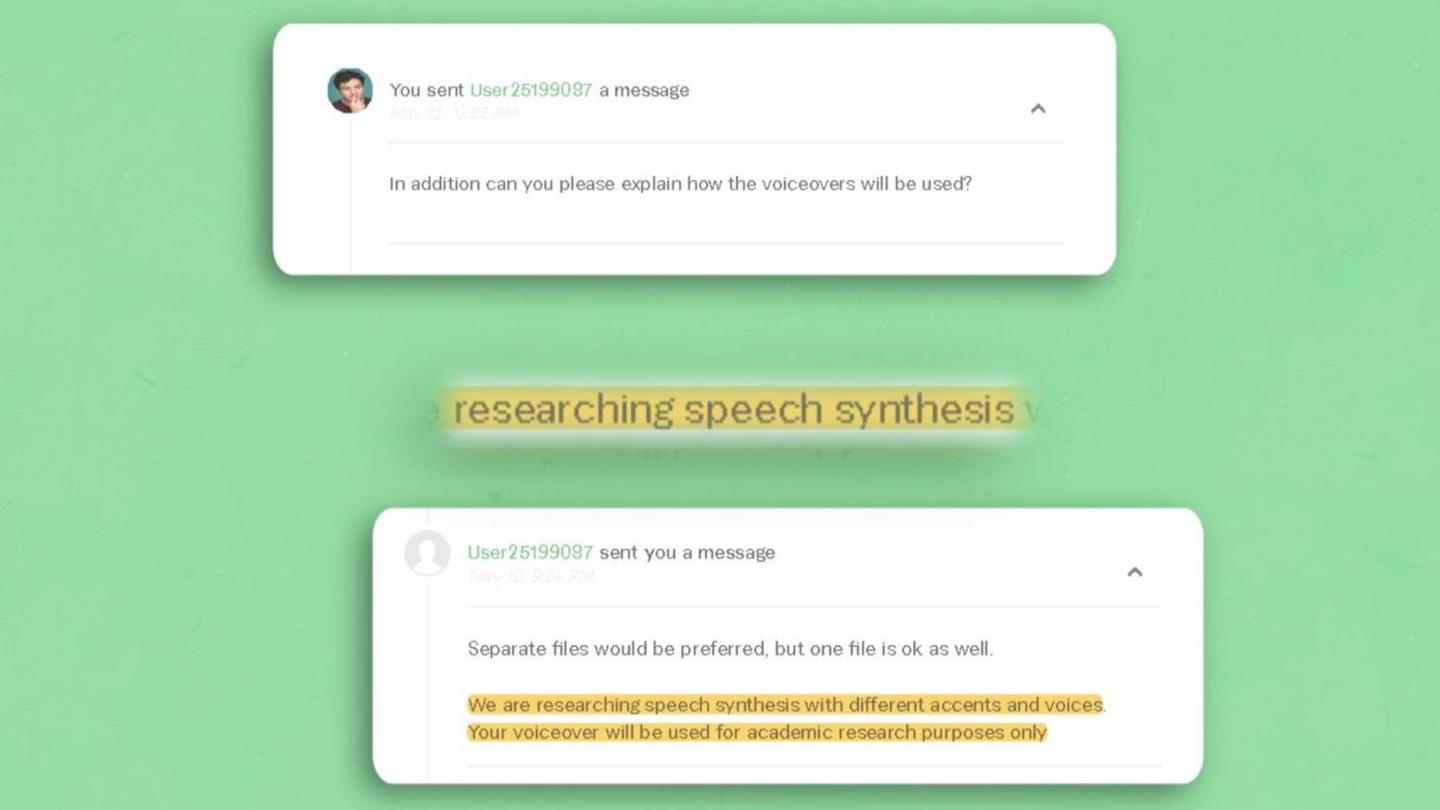

In messages the couple have shared with the BBC, the anonymous Fiverr user says the audio will be used for research into "speech synthesis".

After asking the user to guarantee that the scripts will not be used outside their specific research project, Mr Lehrman asks what the goal of the project is.

"The scripts will not be used for anything else," the user says, "and I can't yet tell you the goal, as it's a confidential work in process sorry haha".

Mr Lehrman asked if the finished files would be repurposed or used in a different order. The user says the files will be used for research purposes only. Mr Lehrman says he delivered the files and was paid $1200.

The link between the anonymous user and Lovo came, they say, from Lovo itself.

They shared the evidence they had found of their voices being cloned with Lovo - who replied they had done nothing wrong, pointing to the communications between them the anonymous user as evidence they engaged with the couple legally.

“In our careers, we've delivered over 100,000 audio assets,” Mr Lehrman said, of their work on Fiverr over the better part of a decade.

“We were able to find this needle in a haystack - they gave us this needle in a haystack.”

In both cases, both Mr Lehrman and Ms Sage say they did not have a written contract, just these conversations. The BBC has not been able to verify the entirety of their conversations. The couple say the user they spoke with also appears to have deleted some messages.

The BBC contacted Lovo on several occasions to request an interview with Mr Lee and to seek a response to the couple’s claims. They did not respond to any of our messages.

What does the law say?

The lawsuit the couple filed in May alleges that Lovo used recordings of their voices to create copies that illegally compete with Ms Sage and Mr Lehrman’s real voices.

The couple say the company did so without permission or proper compensation.

It is a class action lawsuit - meaning they are hoping other claimants will join it, though none have so far.

Professor Kristelia Garcia, an expert in intellectual property law at Georgetown University in Washington DC says the case is likely to centre on an area of US law called rights of publicity.

Sometimes referred to as personality rights, violations of one’s publicity often come from misuse or misrepresentation of someone’s image or voice.

She also says there could likely be a breach of contract regarding the licences Ms Sage and Mr Lehrman granted the user who commissioned the recordings.

"Licences are permission for a very specific and narrow use. I might give you a licence to use my swimming pool one afternoon, but that doesn’t mean you can come whenever you want and have a party in my swimming pool," she told the BBC.

"That would exceed the terms of the licence."

Whatever the outcome of the case, it is another in a long list of lawsuits brought by artists, authors, illustrators, and musicians who don't want to lose control of their work and livelihood.

And they are likely to just be the tip of the iceberg. This week the financial firm Klarna said it planned to use AI to halve its workforce.

Some experts predict 40% of all jobs will eventually be impacted by AI

For Mr Lehrman and Ms Sage though that worrying future is playing out now.

"This whole experience has felt so surreal," Ms Sage said.

"When we thought about artificial intelligence, we were thinking of AI folding our laundry and making us dinner, not pursuing human being’s creative endeavours."

You can hear more on this story on Tech Life, on BBC Sounds.