Mums want answers over pregnancy drug they say harmed kids

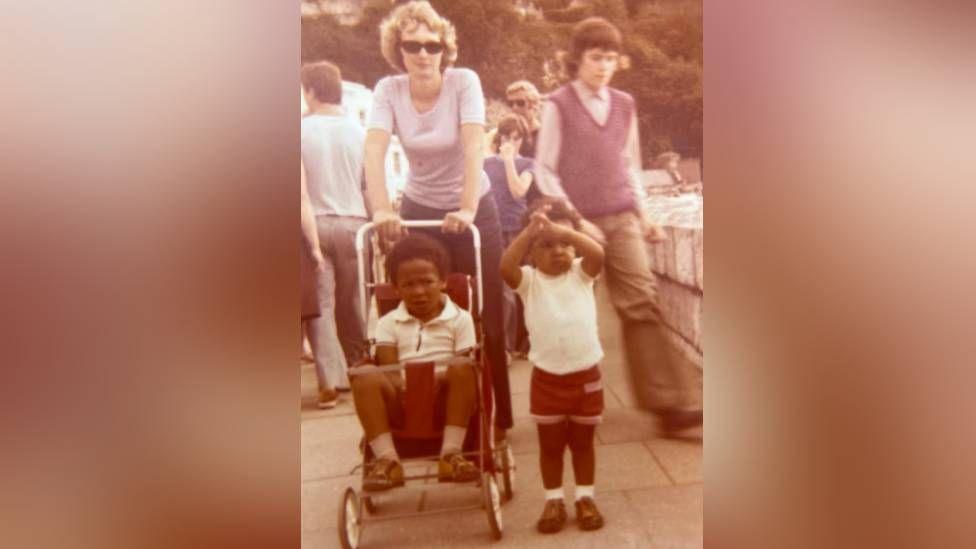

Margo Clarke (left) says son Adrian (right) was a sickly child from the day he was born and needed heart surgery aged eight

- Published

Mothers say they still wants answers over a pregnancy test tablet which they believe led to birth defects.

Margo Clarke, 73, was given Primodos, which contained synthetic hormones and was used between the 1950s and 1970s, before giving birth to her first child, Adrian, in 1970, but said from the minute he was born he was ill.

Former prime minister Theresa May has claimed health service and government of the time "defended itself, rather than trying to find the absolute truth for people" about whether the test was the cause for malformations, stillbirths and abortions.

The drug company involved denies any link between Primodos and birth defects, but families have continued to lobby for recognition and support.

Judge throws out damages claims over pregnancy tests

- Published26 May 2023

Mum's 'guilt' over pregnancy test drug

- Published29 November 2018

Ms Clarke said of her son: "The bigger he got, the worse he got."

She said there were times Adrian's younger brother would need to get out of the pushchair, to allow the older Adrian to be pushed as he was too unwell to walk.

"He couldn't run around, or play football, because he would just be very breathless," she said, adding that his lips would turn blue.

"It was so distressing to see how unwell he was," she said.

He was eventually referred to a specialist and was diagnosed with a hole in the heart, but the family were told he was not ill enough for surgery.

"Because Adrian was mixed race they would say the blue lips were due to his colour and the fact that he couldn't run around was because of his West Indian heritage and his temperament," Ms Clarke said.

"I was called over-anxious, neurotic, and I got to the point where I thought my son was going to die before they made an appointment to see the diagnostic surgeon," she said.

She said the surgeon was "horrified" that Adrian had been left so long and he was lucky to be alive.

Adrian's heart problems meant he was often too unwell to walk and would be pushed in his younger brother's pushchair

Within a month he was taken to London for open heart surgery.

"To say I felt relief is an understatement, because I felt such anxiety over those years, thinking nobody's listening to me," she said.

She said a month after the operation, Adrian was running on the beach with a kite.

Now 53, and having spent more than 30 years working as a nurse, Adrian said he can still vividly remember his early childhood.

He said: "I couldn't do anything with my friends and was always in with the school nurse, needing a lie down."

But he said he was "one of the lucky ones, because I've had a relatively normal life since", adding that other people he believes are similarly affected "are much worse off".

Theresa May commissioned a review into Primodos, which concluded that suffering by women was avoidable

Last year a High Court case seeking damages was thrown out after a judge ruled there was no new evidence linking the tests with foetal harm and "no real prospect of success".

But Mrs May, who stood down as an MP at the 2024 general election, said she feels the thorny issue of evidence is not clear cut.

In 2017, a government review by an expert working group said there was not enough evidence to prove a link between hormone pregnancy tests (HPTs) and birth defects.

"The expert working group actually said 'on balance' there wasn’t a causal link between Primodos and birth defects," said Mrs May.

"But that meant that there was evidence on both sides and they’d come down on that side of the argument. So I think that does need to be looked at again."

She added: "Some children have suffered incredibly during their lives and it is ongoing - it's not finished."

Barbara Stockley (left) helps take care of her son Andy (right)

Mrs May commissioned Baroness Cumberlege to review the use of Primodos, along with vaginal mesh and sodium valproate.

That report was published in 2020 – prompting apologies from the UK and Welsh governments – as it concluded that the use of HPTs should have been stopped in 1967 because of the "suggestion of increased risk" by researchers.

It added that further opportunities for action were missed in 1970, 1973 and 1974.

The official use or "indication" for Primodos was changed in 1970, meaning it was no longer to be used as a pregnancy test.

However, the company that manufactured the drug, Schering, wrote in October 1977 that, in the previous 12 months, thousands of women had still been prescribed it as a pregnancy test.

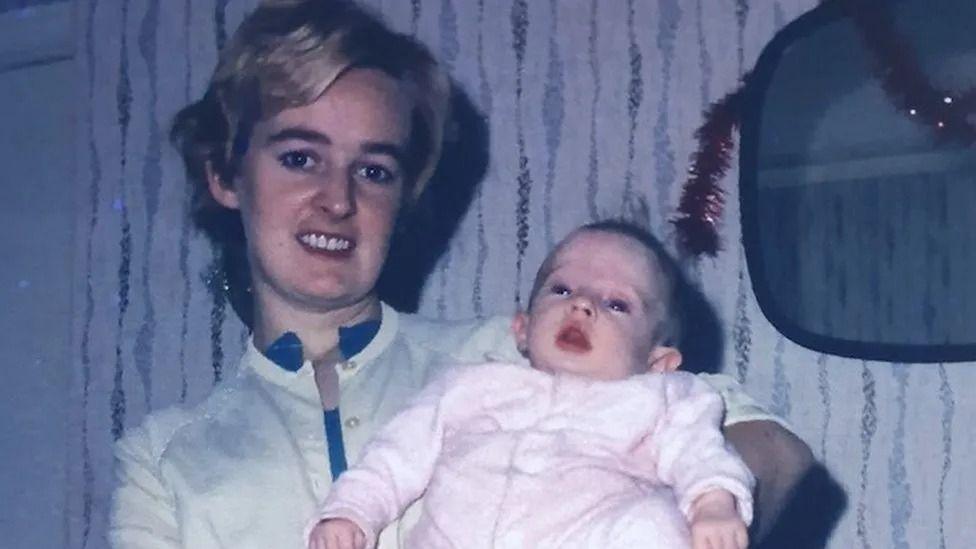

Kathryn McCabe was just 18 when her first pregnancy resulted in a stillbirth

Other women who have taken the drug have different experiences, but their strong belief is that Primodos was at the root of devastating consequences.

Barbara Stockley moved to Cwmbran, Torfaen, when she was given Primodos in 1965.

Her son Andy can’t live independently and needs two-to-one care, which 82-year-old Barbara and her husband coordinate with five personal assistants.

Kathryn McCabe now lives in Powys, but was living in St Helens, Merseyside, when she took the HPT in 1973, aged just 18.

The following year her baby was stillborn, with distressing malformations, which had a profound impact on her.

"You look at others with their prams and wonder why they have their babies and you don’t."

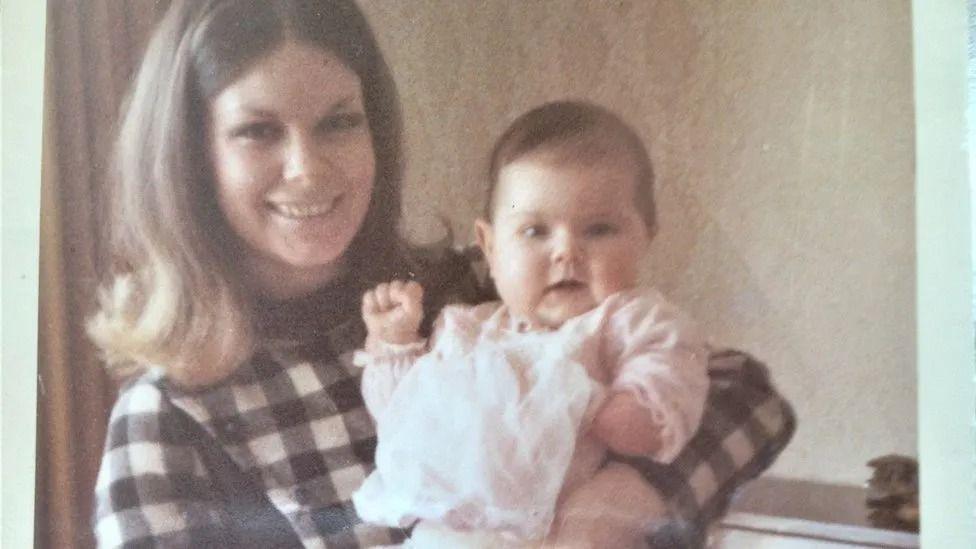

Bethan Dickson (pictured as a baby with her mum Lon) has needed multiple corrective surgeries on her feet

Bethan Dickson’s mum, Lon took Primodos in 1968 when she was living in Newport, and Bethan was born in September that year.

She has needed several operations on her feet over the years, as her toes "were growing across my foot, rather than straight", she said.

She said it was only when she took part in the evidence gathering for the Cumberlege review that she fully considered the psychological and emotional impact.

"I knew I was in pain all the time I was walking – you can see the scars from surgery. But what you don’t see is the exclusion I felt. And that was much deeper than I realised."

Marie Lyon's daughter Sarah was born in 1970 with the lower part of her arm missing

Marie Lyon is chairwoman of the association for children damaged by oral hormone pregnancy tests, and her daughter Sarah was born in 1970s with the lower part of her arm missing.

A key goal for her is an acknowledgement that the women were not to blame.

"Secondly a lot of our families are still caring for their children and have never had any help at all. Women have never had the opportunity to work because of caring for the children," she said.

Pharmaceutical company Bayer said it had "sympathy for the families, given the challenges in life they have had to face".

"Previous assessments determined there was no link between the use of Primodos and the occurrence of such congenital anomalies, and no new scientific knowledge has been produced which would call into question the validity of that conclusion," the company said.

The Department of Health and Social Care said: "The government would review any new scientific evidence which comes to light."