An iconic wildlife park has banned koala cuddles. Will others follow?

Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott and Russian President Vladimir Putin holding Lone Pine's koalas

- Published

For what seems like time immemorial, giving a fluffy little koala a cuddle has been an Australian rite of passage for visiting celebrities, tourists and locals alike.

And for many of them, a wildlife park in a leafy pocket of Queensland has been the place making dreams come true.

The Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary has entertained everyone from pop giant Taylor Swift to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

But as of this month, the small zoo – a Brisbane icon which bills itself as the world’s first koala sanctuary – has decided it will no longer offer “koala hold experiences”.

Lone Pine said the move is in response to increasingly strong visitor feedback.

“We love that there is a shift among both local and international guests to experience Australian wildlife up close, but not necessarily personal, just doing what they do best - eating, sleeping and relaxing within their own space,” said General Manager Lyndon Discombe.

Animal rights groups say they hope this is a sign that the practice - which they argue is "cruel" - will be phased out nation-wide.

They quote studies which have found that such encounters stress koalas out - especially given that the creatures are solitary, mostly nocturnal animals who sleep most of the day.

To have or to hold?

Koalas are a much beloved national icon – priceless in biodiversity terms, but also a golden goose for the tourism industry, with one study from 2014 estimating they’re worth A$3.2bn ($2.14bn; £1.68bn) each year and support up to 30,000 jobs.

However the once-thriving marsupial is in dramatic decline, having been ravaged by land clearing, bushfires, drought, disease and other threats.

Estimates vary greatly, but some groups say as few as 50,000 of the animals are left in the wild and the species is officially listed as endangered along much of the east coast. There are now fears the animals will be extinct in some states within a generation.

And so protecting koalas, both in the wild and in captivity, is an emotional and complex topic in Australia.

All states have strict environmental protections for the species, and many of them have already outlawed koala "holding".

For example, New South Wales – Australia’s most populous state - banned it in 1997. There, the rules state that a koala cannot be “placed directly on… or [be] directly held by any visitor for any purpose”.

But in Queensland – and a select few places in South Australia and Western Australia – the practice continues.

For those willing to fork out, they can snap a picture cuddling a koala, for example at Gold Coast theme park Dreamworld for A$29.95 and the internationally renowned Australia Zoo for A$124.

Steve Irwin even went on the record to argue that these experiences help conservation efforts.

“When people touch an animal, the animal touches their heart. And instantly, we’ve won them over to the conservation of that species,” the late conservationist once said.

And the Queensland government say there are clear rules around this. For starters, the koalas cannot be used for photography for more than three days in a row before they’re required to have a day off.

They can only be on duty for 30 minutes a day, and a total of 180 minutes each week. And females with joeys must not be handled by the public.

“I used to joke, as the environment minister, that our koalas have the best union around,” said Queensland Premier Steven Miles.

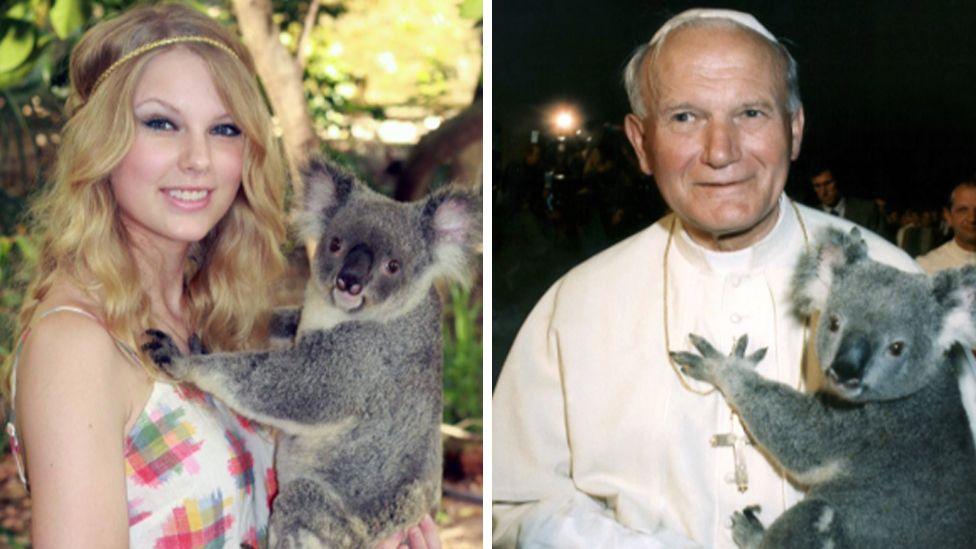

Taylor Swift and Pope John Paul II holding Lone Pine koalas

Right groups have welcomed Lone Pine's decision - but some have called for such attractions to eventually be removed altogether.

“The future of wildlife tourism is seeing wild animals in the wild where they belong," said Suzanne Milthorpe of the World Animal Protection (WAP).

Wild koalas avoid interactions with humans, but at these attractions have no choice but to be exposed to unfamiliar visitors, sights and noises, says WAP – a London-based group which campaigns to end the use of captive wild animals in entertainment venues.

“Tourists are increasingly moving away from outdated, stressful selfie encounters."

The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) Australia also says that "in the ideal world, koalas would never have contact with humans", adding that they would like to see this approach "adopted across the board".

“As cute as they are, koalas are still wild animals in captivity and are extremely susceptible to stress,” Oceania director Rebecca Keeble told the BBC.

“Their welfare is paramount and as they are an endangered species we need to do all we can to protect them.”

But the hope that Lone Pine's move would add momentum towards a state-wide ban appears to have been scuppered.

A government spokesperson told the BBC there is no intention of changing the law - and Lone Pine itself has also clarified that it supports the laws as is.

However WAP says it will keep piling pressure on other venues to leave the koalas on their trees.

“Ultimately, we need the Queensland Government to consign this cruel practice to the history books."

Related topics

- Published11 February 2022

- Published13 April 2022