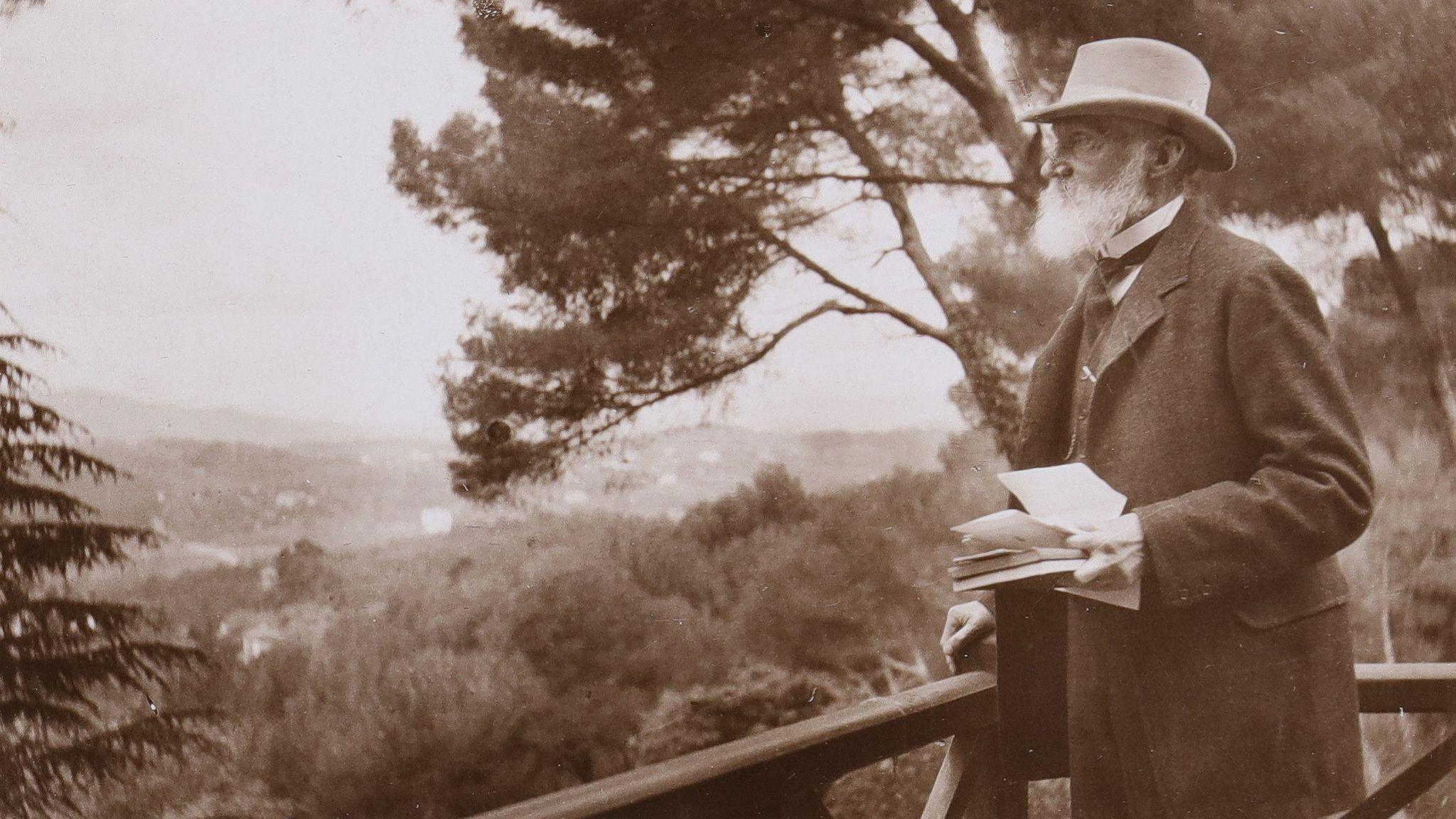

The scientific pioneer who shaped the modern world

Lord Kelvin was one of the world's most famous physicists

- Published

The University of Glasgow is celebrating the 200th anniversary of the birth of one of the world's most renowned scientists.

Lord Kelvin was the professor of natural philosophy at the university for 53 years and established the first physics laboratory in Britain.

He is famed for his ground-breaking work in thermodynamics as well as being instrumental in laying the first transatlantic cable and many other scientific developments of the 19th Century.

To commemorate his legacy, the university is hosting a two-week exhibition and a series of events in honour of his bicentenary.

Over the course of his career he published more than 650 scientific papers

Who was Lord Kelvin?

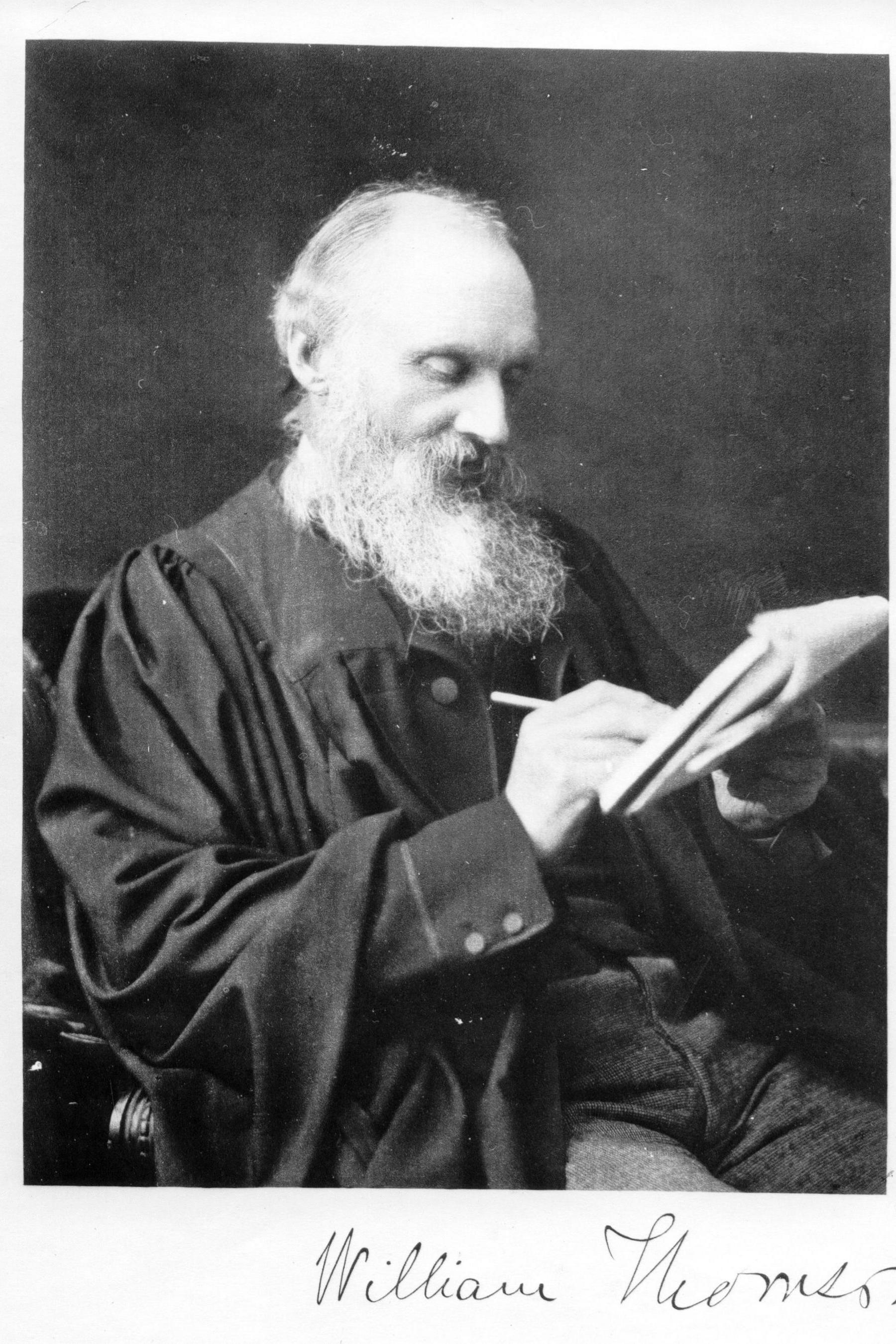

Lord Kelvin was born William Thomson in Belfast on 26 June 1824.

At the age of nine he moved to the University of Glasgow when his father was appointed professor of mathematics - and by the age of 10 he was studying at the university himself.

He later studied at Cambridge and in Europe, where his passion for science and physics grew significantly.

In 1846, he returned to Glasgow as the chair of Natural Philosophy, a position he would hold for half a century.

Over his career, he became one of the most important physicists of the age, renowned by scientists and the public alike.

His work and legacy having shaped the modern world.

Prof Miles Padgett, the current holder of Lord Kelvin's former position at Glasgow, said: "In terms of his legacy, his work on thermodynamics, the transatlantic undersea cable, and his approach to science, integrating it into engineering."

He was the first British scientist admitted to the House of Lords

Prof Padgett said Lord Kelvin made great strides in fundamental science, which seeks to understand the basics of how the world works.

He was a major figure in the development of the second law of thermodynamics, which explains why heat dissipates - for example, why a cup of tea cools down.

He also determined the correct value of absolute zero, the temperature at which molecules and atoms are at their lowest energy points (-273.15 degrees Celsius)

The temperature scale that is based upon absolute zero, Kelvin, is widely used by scientists today and is named after him.

As well as his academic pursuits he was also involved in practical scientific projects such as laying the first transatlantic undersea cable between the UK and the US in 1865.

Facing numerous engineering challenges, he applied his scientific expertise to propose practical solutions.

The following year Queen Victoria knighted him for his efforts.

His work on the undersea cable revolutionised global communication, and such cables remain the backbone of worldwide communication and the internet today.

Later life

In 1892, Lord Kelvin was elevated to the peerage as Baron Kelvin of Largs, named after the River Kelvin near his old lab at the University of Glasgow.

Despite offers from universities worldwide, he remained at Glasgow until his retirement in 1899.

He later became vice chancellor of the university and held the position until his death in 1907 at age 83.

His body was transported from his home in Largs to London, with people lining the streets of Ayrshire to bid him farewell.

His funeral at Westminster Abbey was attended by representatives from around the world, and he is buried next to Sir Isaac Newton.

His work made him a famous figure not only in the UK but also globally.

Prof Padgett said it was incredible that Lord Kelvin combined theoretical science with the desire to solve real-world problems.

"There was nobody scientifically more famous in his time," he said.

"I think there is nobody before or since who has been bestowed with as many honours or recognitions."

Professor Miles Padgett with a bust of Lord Kelvin

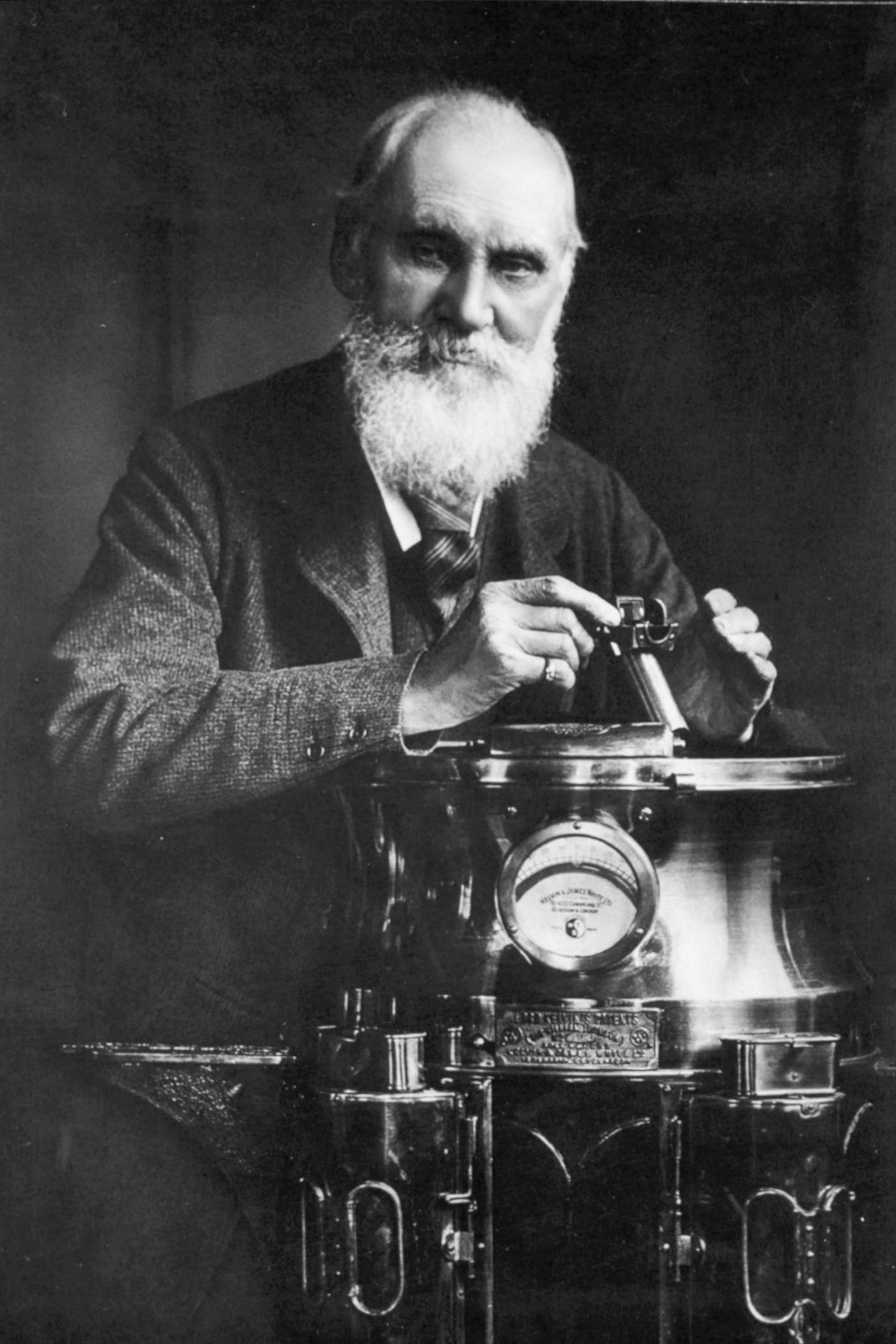

The two-week exhibition at the University of Glasgow is celebrating his life and works and showcasing some of the machines and methods he developed over his scientific career.

During the exhibition, there will be a number of talks presenting Lord Kelvin's work, how it shaped the modern world, and how his work is being built upon.

More information about Lord Kelvin's 200th celebrations. , external