The huge challenges in creating fusion power plant

Fusion has often been criticised for always being '10 years away'

- Published

The project to build a nuclear fusion reactor in Nottinghamshire has been described as the "UK's Nasa moment".

But beyond the optimism of an event showcasing the scheme, how close is it to becoming a reality?

Is the promise of clean, cheap and secure energy still obscured by huge scientific, engineering and economic hurdles? And is it safe?

Two experts give us their take.

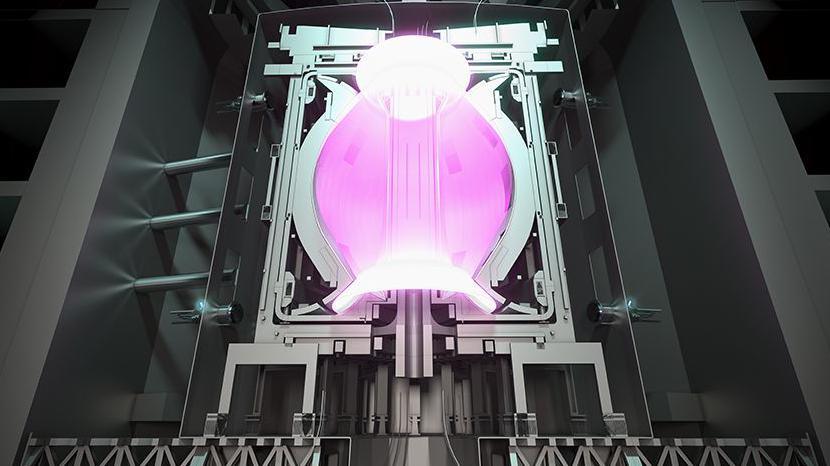

Former coal fired power station West Burton A, near Retford, was chosen as the location for the Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production (STEP), in October 2022.

However, even if investors are found and construction completed on schedule, the facility is unlikely to open before 2040.

Explaining the process, Dr Aneeqa Khan, lecturer in nuclear materials at the University of Manchester, said: “Nuclear fusion is the process that powers the Sun, where two nuclei fuse together, liberating huge amounts of energy.

“Recreating the conditions in the centre of the Sun on Earth is a huge challenge.

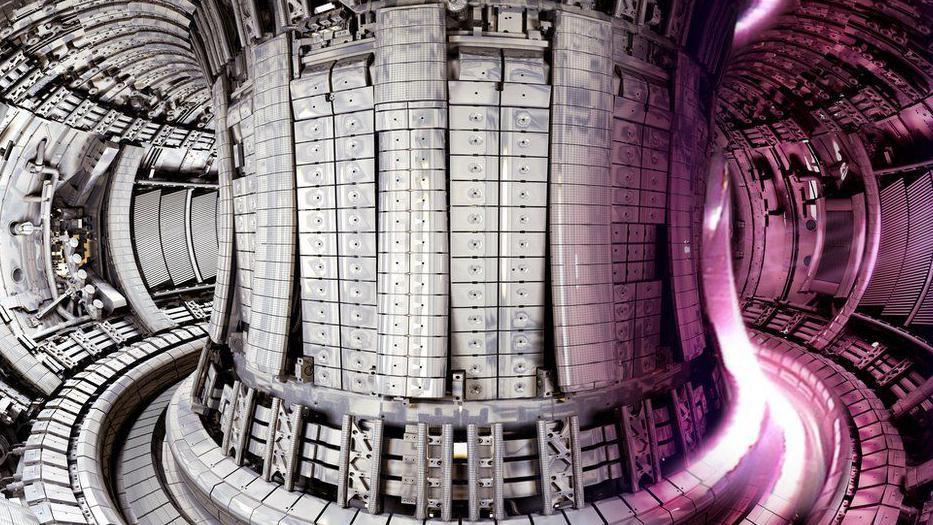

“We need to heat up isotopes of hydrogen gas so they become the fourth state of matter, called plasma.

“In order for the nuclei to fuse together on Earth, we need temperatures 10 times hotter than the Sun – around 100 million Celsius."

The promise of fusion is great - but so are the challenges

Dr Brian Appelbe, a research fellow in nuclear fusion at Imperial College London, said fusion differed from traditional nuclear power – fission - in several fundamental ways.

He said: “Fission is about breaking heavy element apart, fusion is about forcing lighter element together.

“The amounts of energy that are released with fusion are far higher than fission.

“And the elements being used, like hydrogen, are far more widely available than the fission fuels. Some, like deuterium, a form of hydrogen, can be sourced from sea water.

“This is a much cleaner source of energy because it makes less radioactive material and it is radioactivity which doesn’t last as long.”

Dr Khan added: “We are still a way off commercial fusion. Building a fusion power plant also has many engineering and materials challenges.

“However, investment in fusion is growing and we are making real progress.

“We need to be training up a huge number of people with the skills to work in the field and I hope the technology will be used in the latter half of the century.

“Global collaboration is key in achieving this.”

Dr Appelbe said: “The news about the Nottinghamshire site is very exciting and there is a lot of development happening but we are still at the scientific stage of developing fusion.

“There is a real momentum building and I am optimistic about overcoming the scientific hurdles to building a functioning fusion power plant but I’m not an engineer or economist.

“But I wouldn’t want to put a timescale on it.”

Public opposition has been one of the most powerful obstacles to nuclear power

One of the practical problems which has dogged traditional nuclear power is public opposition, often based around fear of leaks and accidents.

Dr Appelbe said: “I’d certainly live next to a fusion station.

“It uses small amounts of fuel very quickly, so there are not the large amounts of fuel which are around for much longer with fission, which have been the source of some accidents such as Chernobyl.

“This, combined with the challenge of keeping a fusion reaction going, means there is no way you can have catastrophic runaway issues.”

Follow BBC Nottingham on Facebook, external, on X, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external or via WhatsApp, external on 0808 100 2210.

Related topics

See more

- Published25 July 2024