Ever since I was a child I have loved wildflowers. I have fond memories of the woods in Sussex, where I grew up, filling with primroses early in the year and carpeted with bluebells in the spring.

I always used their nicknames - "eggs and bacon" for birds-foot-trefoil (a native plant known for its yellow slipper-like petals) and "bread-and-cheese" for the young shoots of the British tree hawthorn, which my friends and I would eat. And pretend to like!

We picked rosehips from hedges too, which we split open to make itching powder, perfect for playground pranks.

But later in life, on my walks through the countryside, I began to notice dwindling numbers of wildflowers. I missed the grasslands, bursting with colour, that I'd so enjoyed in my childhood.

'As a bee lover I'm on team pollinator - which is one of the reasons why my husband and I decided to plant our own wildflower meadow,' says Martha (pictured right)

According to the charity Plantlife, approximately 97% of wildflower meadows have been lost across the UK since the 1930s, while species-rich grassland areas, which used to be a common sight, are now among the most threatened habitats.

"It's definitely a story of severe overall decline, both in the cover of flowers but also the diversity," explains Simon Potts, professor of biodiversity and ecosystem services at Reading University.

So, what will happen if there isn't more intervention to save wildflowers? What will the future look like?

"Awful, in a word," says Prof Potts. "If we, let's say, take a scenario where we just continue business as usual as we are now, we will still keep losing our wildflowers.

"And with that, we lose the beneficial biodiversity like the pollinators and the natural enemies of pests."

'My husband cut the hay, initially trying with a scythe - Poldark-style - but a small tractor does the trick in a less backbreaking way'

As a bee lover I am on team pollinator - which is one of the reasons why my husband and I decided to plant our own wildflower meadow. Not just for the beautiful colours but for the vibrancy of the bees, butterflies and moths flying around, which need that habitat.

Yet since then, I've come to understand that the loss of wildflowers could bring other perhaps more unexpected consequences too.

Higher food prices, less wildlife

"The consequence will be for farmers," argues Prof Potts. "They will get low yields and poor quality crops, consumers will have to pay higher prices. Our environment will be degraded, eroded, will have less wildlife.

"Many of them [wildflowers] produce nectar and pollen, which is super important for things like wild bees, hoverflies, and butterflies, that can pollinate crops."

Prof Daniel Gibbs, food security lead at the University of Birmingham's School of Biosciences, also has concerns about the long-term consequences.

"Over time, and alongside pressures from climate change and land degradation, this could make our food system more fragile, and negatively impact food security," he says - meaning we could, for example, find ourselves with more limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables.

'Farmers may have to rely more on manual pollination or we may need to look to increasing food imports, both of which can drive up prices,' says Prof Gibbs

There are also studies showing that fields near wildflower-rich margins or meadows produce better-quality fruit and higher yields.

"Wildflowers can also support some bugs, like spiders and carabid beetles… [which] do an absolutely fantastic job in controlling some of the pests that we get on crops - that can either damage the crop or sometimes lower the quality of the produce," adds Prof Potts.

He describes wildflowers as almost like little factories, pumping out beneficial bits of biodiversity that can help with food production.

"Farmers may have to rely more on manual pollination," Prof Gibbs says. "Or we may need to look to increasing food imports, both of which can drive up prices."

Farming under strain

Multiple factors are behind the decline. Sarah Shuttleworth, a botanist with Plantlife, argues that certain intensive farming methods have contributed.

But some intensive farming methods have also allowed farmers to grow food for the country - and farmers I spoke to pointed out that they face tough financial choices.

Though there have been government subsidies in place for years, meaning farmers are paid by the government to support wildlife on their land, since Brexit the way these grants are paid has changed, with different schemes designed in each of the devolved nations.

In England, there has been frustration in some quarters about the speed and rollout of the grants and the fact that some schemes have been paused - such as the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI), though this is due to reopen, while others extended at the last minute, leaving farmers less able to plan ahead.

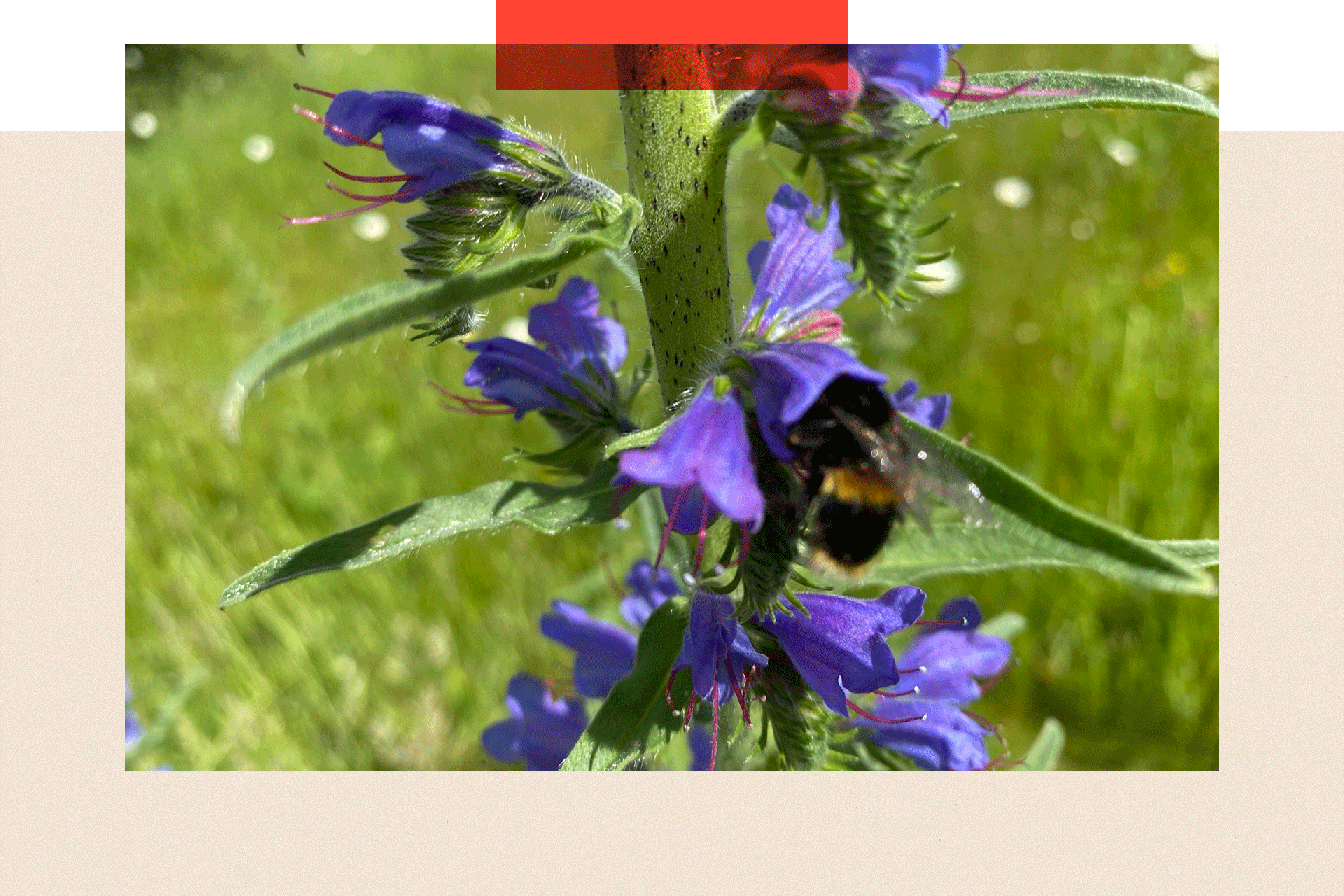

The nectar and pollen of wildflowers is important for things like wild bees, hoverflies, and butterflies, says Prof Potts

Speaking about the SFI scheme, a Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) spokesperson told the BBC: "We inherited farming schemes which were untargeted and underspent, meaning millions of pounds were not going to farming businesses.

"We have changed direction to ensure public money is spent effectively, and last year all the government's farming budget was spent."

They also acknowledged that wildflowers are vital, providing food and habitats for pollinators and wildlife, as well as improving biodiversity, and added: "We are backing farmers with the largest nature-friendly budget in history and under our agri-environment schemes we are funding millions of hectares of wildflower meadows."

As part of its new deal for farmers, Defra said it has committed nearly £250m in farming grants to improve productivity, trial new technologies and drive innovation in the sector.

David Lord, a third-generation farmer in Essex, says he has never known farming to be under such strain

Mark Meadows, Warwickshire chair of the National Farmers' Union (NFU), maintains 6m (20ft) wildflower strips around many of his fields. He feared that without an extension to his current agreement with Defra he'd have to return some wildflower margins to crop production.

"I'd love [to] be profitable enough [to] say 'Look, we'll leave 5% of our farmland,'… but agricultural costs have gone up a lot," he says.

Other farmers share similar tales. David Lord is a third-generation farmer in Essex and member of the Nature Friendly Farming Network.

"I'm 47 and I've never known farming to be under so much strain," he says.

Knowing what funding for nature recovery on farms will be in place in future years is, he says, crucial. "It takes time and care and cost to maintain [wildflowers]... A lot of farmers aren't going to be minded to just keep these habitats in place without the funding."

Why we created a meadow

There are some glimmers of hope.

Prof Potts says there has at least been a slowdown in decline over the last couple of decades - and perhaps a limited recovery for some species.

"I think [this] reflects some of the agricultural practices that have been a bit more nature-friendly."

Nature writer, and author of Flora Britannica, Richard Mabey, agrees that the decline in wildflowers is far from universal.

Certain species such as cow parsley, yarrow and knapweed are in fact spreading, and he welcomes an influx of non-native plants and "garden escapes", such as snowdrop and buddleia.

Even so, Prof Potts says: "It is the most precious things that we're losing the most of." This includes cornflowers, corncockle and corn marigold - what he terms the iconic British countryside flowers.

And the overall decline is why my husband and I decided to create our own wildflower meadow from an overgrown arable field.

The most spectacular year for Martha Kearney's meadow was last summer

There was a field next to our house, which I had put beehives in, with permission from the owner. I had often thought it would be wonderful to create a wildflower meadow around those hives, so when the opportunity arose to buy the field, we decided to go ahead.

A conservation specialist advised us on where to buy the seed. It was particularly important to get some yellow rattle seed, which helps keep more dominant grasses in check. This in turn gives other wildflowers more opportunity to gain a foothold.

Our first year after sowing was amazing. A patriotic bloom of red, white and blue burst across the field. The red was from poppies which came from the disturbed ground. The white was ox-eye daisies, bladder campion and wild carrot, with spires of bright blue from viper's bugloss.

The colour has changed over time - the splash of red did not return, but different wildflowers arrived in their place.

More from InDepth

US farmers are being squeezed - and it's testing their deep loyalty to Trump

- Published15 September

The most spectacular year was last summer. Orchid seeds I'd scattered many years before and almost forgotten about, managed to flower. We counted more than 100 bee orchids — which to a bee lover like me, was the climax of years of work.

In fairness, I should admit it's years of my husband Chris's work. He found an old-fashioned seed fiddle for us to use — a hand-held device used to scatter the seeds in a controlled way, operated as though drawing a bow across a violin.

He also cut the hay at the end of summer, initially trying with a scythe - Poldark-style - but ultimately finding a small tractor does the trick in a less backbreaking way.

Watch: Martha Kearney uses a seed fiddle to create her meadow

Of course, many people are not in the fortunate position we found ourselves in, of being able to create a wildflower meadow. And in the UK, you cannot plant wildflowers just anywhere — you would most likely need the landowner's permission.

But growing numbers of people are trying to create their own patches of wildflowers. Plantlife reports that more and more are joining its No Mow May initiative — an annual campaign to let wildflowers grow freely, by packing away the lawnmower.

Sarah Shuttleworth says just a small spot can make a difference, especially when it comes to pollinators. "Anyone who has a patch of grass could do their bit… the idea is that you're recreating a meadow-type management scheme, but in a very, very micro scale."

Time for a radical rethink?

The charity would like to see wildflower habitats being given the same kind of protection as other precious landscapes. Meanwhile Prof Potts thinks, "We need a bit more of a radical think about how to support farmers to do the right thing."

New housing developments could also prove a way to create wildflower meadows. Under the government's Biodiversity Net Gain scheme, set up under the Environment Act, developers creating building sites are obliged to ensure the same amount of biodiversity at the end of the project, as they had at the start, plus 10%.

Ben Taylor manages the Iford Estate, farming land near Lewes in Sussex. For a recording of Open Country on Radio 4, he showed me with great pride around a new wildflower meadow, which was part of a 90-acre site, funded as a pilot by the scheme.

"We have seen hares here now, which we never had a year or two ago, before we started doing this. So it's really exciting..."

'Our first year after sowing was amazing. A patriotic bloom of red, white and blue burst across the field'

But, I wondered, does it make sense to take all of those acres of land out of food production?

Mr Taylor says the soil was poor there anyway. "You have to have nature to be able to grow food," he adds. "Because you need the pollinators as you need the ecosystem, the food chains, the soil webs and everything else to be able to grow food sustainably in the long-term - so I like to think of it as a reservoir of biodiversity."

Many ecologists also want us to look beyond the benefits the wildflowers provide for us.

"Those species are just valuable in their own right, regardless of what they do or what they provide… They've also got their own right to be," argues Dr Kelly Hemmings, associate professor in ecology at the Royal Agricultural University.

Richard Mabey stresses a similar point. "They are important, in my view, for ethical reasons, simply because they exist.

"Beyond that they are the infrastructure of all other life on the Earth, the fundamental base of the food chain."

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published - click here to find out how.