'Mum killed dad but I fought to free her'

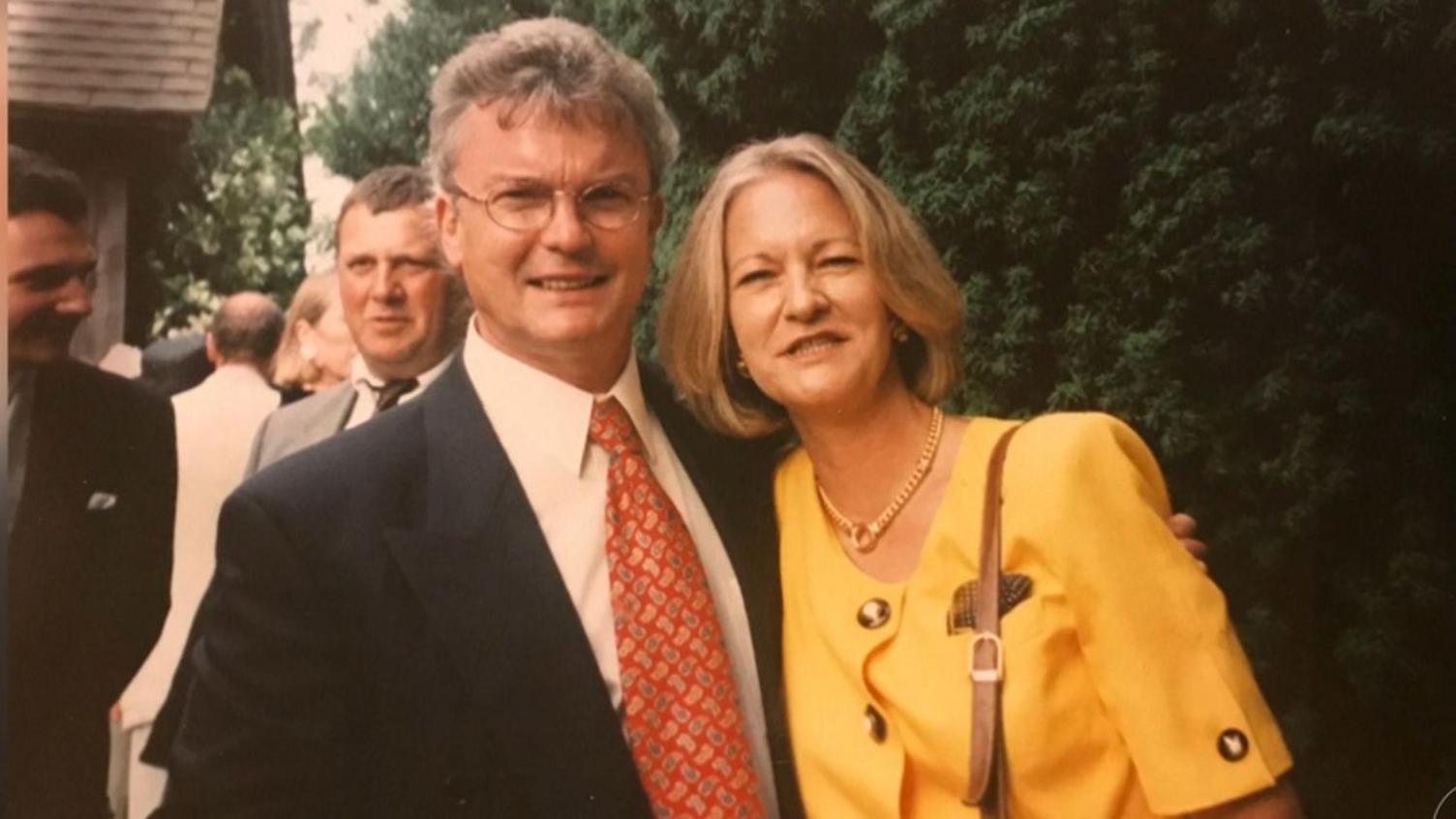

Sally Challen (right) suffered decades of abuse at the hands of her husband, Richard (left)

- Published

"I had a pristine frontage of a middle-class home - no one thought it could happen behind those doors, but it did."

David Challen successfully campaigned to free his mother, Sally Challen, from prison in 2019, almost nine years after she had killed his father, Richard, with a hammer.

She had suffered decades of coercive control by her husband, which David said had become "normalised" within the family home in the wealthy suburban village of Claygate in Surrey.

David, now a domestic abuse campaigner, has written a book, called The Unthinkable, about the family's experiences, and said more needs to be done to protect victims.

Speaking to Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg on BBC One, he said: "She'd done the worst act anyone possibly could do. [She] took away my father.

"I couldn't understand it, but I knew something had been rolling... something was happening and I just didn't have the words."

David Challen spoke to Laura Kuenssberg ahead of the release of his book

A law passed in 2015, which recognises psychological manipulation as a form of domestic abuse, helped secure Mrs Challen's release from prison after she had been jailed for life for murder in 2011.

She was freed after her conviction was quashed in February 2019 and prosecutors later accepted her manslaughter plea.

Coercive control describes a pattern of behaviour by an abuser to harm, punish or frighten their victim and became a criminal offence in England and Wales in December 2015.

From the outside, the family appeared happy - but his mother's abuse had become "normalised", David said

David said the description of coercive control had set him and his mother "free".

"It gave us a language to describe what was going on in that home, to describe the insidious nature that is mostly non-physical violence," he said.

Not having a name for the abuse had "robbed us of our right to have an ability to protect ourselves," he added.

He now uses his experience of "intergenerational trauma" to help others, with a book telling the family's story being released on Thursday.

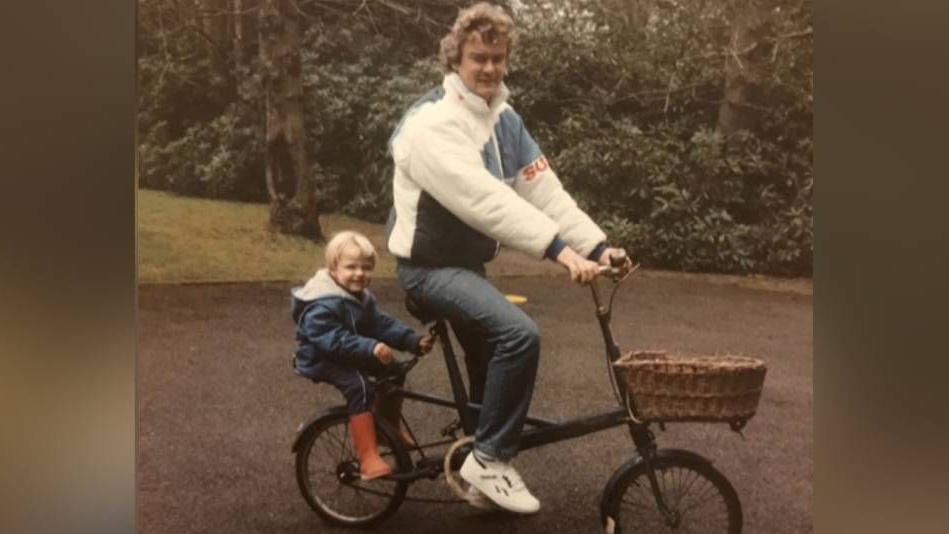

David said he always knew there was something wrong at home

"I buried my childhood with my father, so I had to dig up the past to find the child I had left behind," he said.

"It was the child that I always hid because I didn't know how he experienced that world.

"But I knew I was born into this world with a gut feeling that [there was] something inherently bad about my father, and I never knew why.

"I normalised the coercion and control in my home, this life of servitude that my mother lived under... sexual violence was routine."

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this article, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line.

He said he wrote the book to "give voice to what it's like to grow up in a home where domestic abuse wasn't the word - it was coercive control and it didn't appear on my TV screens".

But, a decade on, "we're not tackling it enough", he added.

"I continue to speak out because I don't want these events to happen again."

Related topics

- Published28 February 2019

- Published3 January 2019