Toxic metals in peatlands could pollute waterways and harm health

PhD student Ellie Purdy "jumped" at the chance to work on the project

- Published

Toxic heavy metals stored in peatlands in the UK could cause health risks to humans, animals and agriculture if ecosystems are not cared for, researchers at Queen's University Belfast have found.

They warn that wildfires and the effects of climate change could see decades' worth of pollutants like lead, arsenic, mercury and cadmium, released into our natural water systems.

The health risks from those pollutants have been seen before - a medical expert linked the presence of cadmium at a former steel site in Corby, Northamptonshire, to birth defects in animals.

The scientists say the findings make re-wetting and restoring peatlands even more vital, to protect environmental and human health.

Industrial pollution

Peatlands are well-known carbon sinks, locking away greenhouse gases in their watery depths.

They have also been absorbing the industrial pollution that humans have been generating for two centuries.

The QUB team, led by Professor Graeme Swindles, has been examining cores from across the UK, Ireland and further afield, as part of a global study with many other organisations.

Stored pollution has even been found in samples from the remote Northern Arctic.

"It's quite staggering to find such high levels in our peatlands that you think are these incredibly pristine places in many ways," said Prof Swindles.

"But no - they have been affected by our pollution."

Professor Graeme Swindles has been leading the project

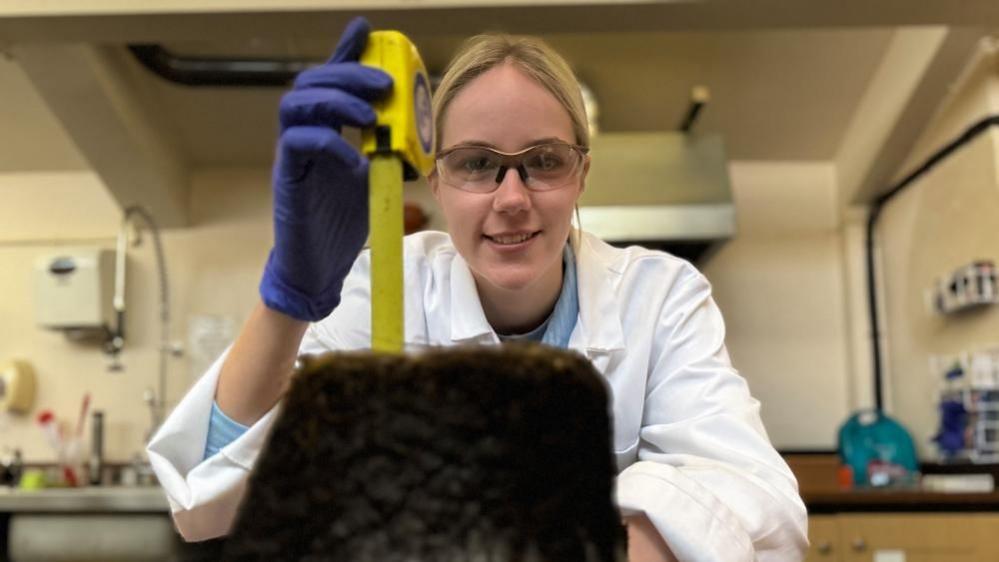

PhD student Ellie Purdy "jumped" at the chance to work on the project.

"It's basically just about how what we're doing is affecting the environment," she said.

"And even though these contaminants were once stored in these peatlands they're now being released under climate warming."

She said it is a cause of concern for the future.

She has been looking specifically at cores from Ellesmere Island in the Canadian High Arctic. Finding heavy metal contamination in "an extremely remote area with little civilisation around", it has been "eye-opening" for her.

"It just shows how connected we are throughout the globe," she said.

Dr Richard Fewster has focused on the potential impact of the warming climate

Peatlands cover about 12% of Northern Ireland. In good condition, they form new peat at a rate of just 1mm a year.

But more than 80% of them are in a poor or degraded state, largely due to burning or being drained for peat extraction.

Experiments in the QUB labs evaluate how a changing climate might affect them.

Dr Richard Fewster has focused on the potential impact of three likely scenarios - a warming climate, wildfires and summer droughts.

While all three affect how peat behaves, burning has potentially the greatest impact.

A core sample showing darkened peat at the surface where two centuries' worth of pollution is stored

Dr Fewster said: "We're seeing that burning actually mobilises some of the metals within the peatland much more rapidly, in a sort of a 'big pulse' event early on in the experiment that we don't see in cores that are left intact.

"So one of the really early findings that we have is that protecting our systems in a wet, stable, intact condition is really important for locking these peat metals, these pollutants, away in our peatlands and preventing them from being released."

A long-awaited peatlands strategy from the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs requires Executive approval.

The draft Climate Action Plan says Northern Ireland "will have to dramatically increase its annual peatland restoration activity" to meet Climate Change Committee recommendations of restoring 10,000 hectares by 2027.

James Devenney from Ulster Wildlife has been leading restoration work

At Garry Bog near Ballymoney in County Antrim, more than 3,000 dams have been created to block drains and raise the water table back up.

The peat here runs to a depth of at least nine metres, which means it has been forming for more than 9,000 years and sequestering carbon for all that time.

James Devenney from Ulster Wildlife has been leading the restoration work at the site.

He said peatlands are our most significant, most impactful, terrestrial carbon sinks.

"So the fact that we have 12% cover in Northern Ireland of peatlands - deep peat in a lot of cases that's greater than 50 centimetres - there's a huge scope of work that can be done.

"Northern Ireland has a big part to play in tackling climate change."

Prof Swindles said the message from the work of his team in the lab at QUB could not be starker.

"It's really clear we need to ensure these peatlands are kept wet. We need to restore them, rehabilitate them, block drains.

"And we need to stop burning peatlands."

- Published21 January 2024

- Published6 May 2022