What is the story behind Northampton's Great Fire?

The Great Fire of Northampton whipped through the tinder-dry town in 1675, fanned by unexpectedly strong winds

- Published

It is 350 years since a fire ripped through one of England's most important market towns.

The Great Fire of Northampton destroyed 700 out of 850 buildings and claimed 11 lives within hours of starting on 20 September 1675.

The anniversary has been commemorated with a series of events in the town over six months.

But, what caused the devastating blaze and how did Charles II help with its rebuild? The BBC has been finding out.

'Densely packed and filthy'

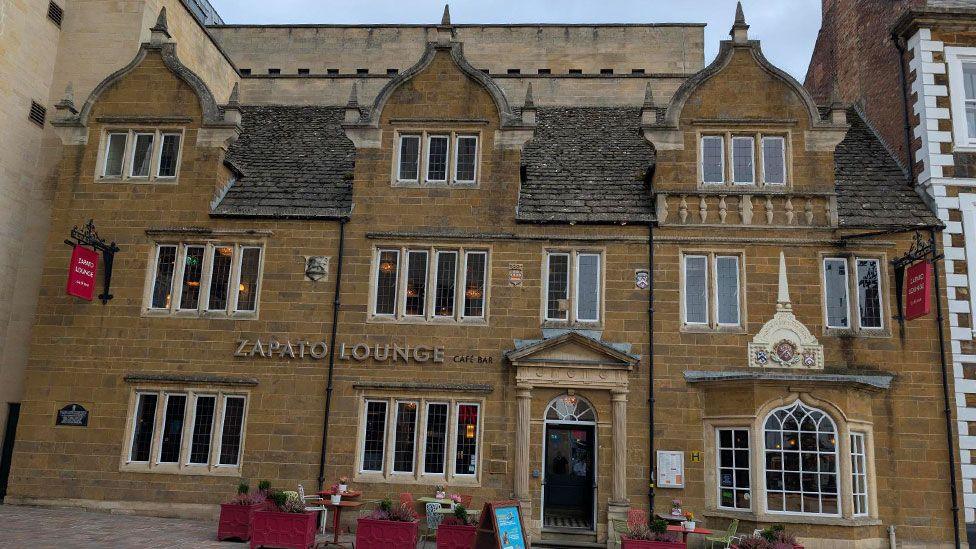

One of the few houses to survive the conflagration was Hazelrigg House, part of which did need rebuilding

Northampton in 1675 was still essentially a medieval town, densely packed with lots of alleyways, having evolved in a random way over centuries, according to Alan Clark, an expert on the town's history.

"At the same time there was a population increase in what was a golden era of English market towns in terms of commercial activity, which meant the population density was such that properties were simply ramshackle, insalubrious and often filthy," he added.

The vast majority of the buildings were thatched and built from timber frames with plaster walls imbedded with straw and horse hair - all highly flammable.

Dr Clark said the local authorities were well aware of this, repeatedly urging people to maintain what fire precautions were in place.

Meanwhile, conditions across the country were tinder-dry.

"[The year] 1675 is known for a terrible drought, which began in January and continued throughout the year," he said.

"So along with supplies like hay for horses and barrels of alcohol, it was a recipe for disaster," he added.

'Going up in a whoosh'

James Miller (left) and Earl Spencer (right) have been researching the Great Fire of Northampton

The fire is believed to have started accidentally on St Mary's Street, now Chalk Lane.

Dr Clark said: "It's reported that late in the morning of 20 September, a woman put a kettle on an open fire and left it unattended, so this is just a simple human occurrence - except that on this day a very stiff wind, blowing directly from the west, had been suddenly picking up in speed and strength.

"It may have contributed to the ignition of the fire at that lady's property and fanned those flames into and affecting other properties."

An eyewitness riding past the town and bound for London would later describe the astonishing speed of the blaze that ripped through the town.

Earl Spencer, who has has written several historical books and co-hosts a history podcast, said: "I've read contemporary accounts that say the Great Fire of Northampton was more devastating than the Great Fire of London (1666) for its scale.

"You think of these quite compressed, highly combustible buildings going up in a whoosh."

Trapped in the market square

Many of the townsfolk fled to the safety of the market square - reportedly the largest in the Midlands - only to seek escape through the Welsh House (above)

As the blaze began at about midday, people could grab some of their possessions and flee, said art historian James Miller, who worked on the town's anniversary events.

"They weren't in their beds, they knew it was coming and they all rushed to the large Market Square because they thought that would be quite safe," he said.

But the square was packed with more combustible material, which also caught fire and "whoosh off it went" trapping them, he said.

Just as they feared the worst, the terrified people discovered an opening at The Welsh House, in the square's north-eastern corner, enabling them to cross its grounds by the side of the property to make their escape.

Meanwhile, the fire reached All Hallows Church, south of the Market Square, which supercharged the blaze.

Dr Clark said: "Its central crossing tower becomes a chimney and magnifies, radiates and increases the intensity of the heat and so the fire reignites and this then allows it to leap spaces and to spread and continue eastward to St Giles' Church."

Then the weather that had helped whip up the conflagration, suddenly came to the town's aid.

Mr Miller said: "The next morning, a gale took place and it drenched the town - it had burnt down but within 36 hours, it was sodden and the fire was out."

'You should have seen the looting'

All Saints' Church stands on the site of the burned-out All Hallows' Church and was built within five years of the devastating blaze

Thousands of people were now without their homes - more than 80% of the town's properties were uninhabitable.

They were about to benefit from a rapid rebuild thanks to lessons learned from the Great Fire of London - and royal support.

Dr Clark said it had taken five months to pass an Act of Parliament for London's rebuild and this set the foundations for helping destroyed towns and cities going forward.

"One of the first buildings to be constructed was the Sessions House in 1678, because it is regulating the economy, levying taxes and fines and reconstitution of law and order," he said.

"This mattered, because an anecdote from the time was, 'If you thought the fire was bad, you should have seen the looting'."

Next to be rebuilt was All Saints' Church, constructed on the foundations of All Hallows and funded by the ecclesiastical authorities.

Dr Clark said, for many people, the immediate impact of the blaze was devastating - "exceptional poverty becomes rampant, people starve and are left impoverished".

'An act of reconciliation'

Charles II (1660 to 1685) became one of the chief benefactors of the construction effort

Leading local figures stepped in with offers of help.

The Reverend Oliver Cross, the rector of All Saints' Church, said: "The Earl of Northampton turned up the day after the fire and donated £150 for the immediate aid effort."

Others who helped the rebuild efforts were chief justice Sir Richard Rainsford, who had experience working on the aftermath, external of the Great Fire of London, and Sir Roger Norwich.

Prior to the fire, Charles II had pulled down Northampton's town walls to punish its people for Parliamentarian supporters during the English Civil Wars of the 1640s and 1650s.

Father Cross said: "It was only after the Great Fire that an incredible act of reconciliation took place between the Parliamentarian town and the crown, which meant Charles II became the chief benefactor of the construction effort.

He donated more than 1,000 tonnes of timber to reconstruct All Saints' Church and halved the town's taxes for seven years following the fire.

All Saints' Church still remembers that help by marking Oak Apple Day, which commemorates the restoration of the Stuart kings to the English throne, said Father Cross.

Oak Apple Day commemorates King Charles II, who famously hid in an oak tree after the Battle of Worcester in 1651

The Great Fire of Northampton: 350 years on

Exploring the fire which crippled the town, destroying a majority of the buildings, and leaving thousands homeless, on 20 September 1675.

Get in touch

Do you have a story suggestion for Northamptonshire?

Follow Northamptonshire news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external.

Related topics

- Published5 September

- Published12 January

- Published18 May

- Published1 July