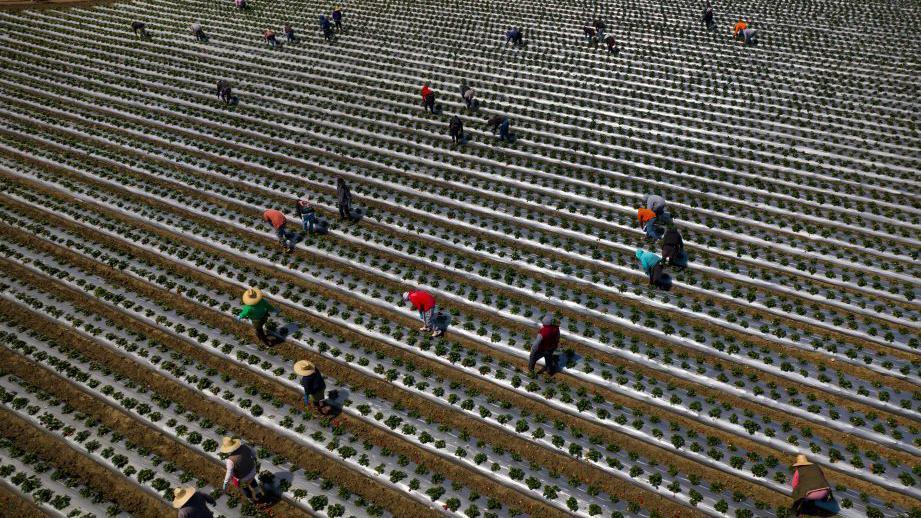

Migrant farm worker deaths show cost of the 'American Dream'

Many agricultural farm workers in the US are immigrants

- Published

Last year, Hugo watched a friend die in a vast field of sweet potatoes, his lifeless body leaning against a truck tyre – one of few shaded areas on the sweltering North Carolina farm.

“They forced him to work,” Hugo recalled. “He kept telling them he was feeling bad, that he was dying.”

“An hour later, he passed out.”

Hugo, which is not his real name, has spent most of his time in the US as a migrant farm worker, a job where the pay generally hovers at or below minimum wage, and where work conditions can be fatal. The BBC agreed to use a pseudonym because he expressed concern he could face repercussions for speaking out about the incident.

Hugo departed Mexico in 2019 with a visa to work in the US, leaving behind a wife and two children to pursue the “American Dream”, unsure of when he would return. Or if.

His friend who died on the sweet potato farm was Jose Arturo Gonzalez Mendoza.

It was Mendoza’s first trip to the US for work. He died within his first few weeks on the farm in September 2023. Mendoza, 29, had also left his wife and children in Mexico.

“We come here out of need. That’s what makes us come to work. And you leave behind what you most wished for, a family,” Hugo says.

From farmers and meatpackers to line cooks and construction workers, migrants often do dangerous jobs where workplace deaths typically go unnoticed by the wider public. But in the past year, the issue has been thrust into the spotlight, by multiple high-profile deaths and by a migrant crisis at the border that has amplified anti-immigrant rhetoric.

The day Mendoza died, the heat was intense.

Temperatures hovered around 32C (90F). There was not enough drinking water for workers and the farm only allowed one five-minute break during hours-long shifts.

The one place to escape the heat was a bus without air conditioning parked in an open field.

The details are outlined in a report by the North Carolina Department of Labor, external, which fined the farm - Barnes Farming Corporation - this year for its “hazardous” conditions.

The report confirmed the death on the farm and mentioned that management "never” called healthcare services or provided first-aid treatment.

In the hours before his death, Mendoza “became confused, demonstrated difficulty walking, talking and breathing and lost consciousness", the report said.

Another farm worker eventually called emergency services, according to the report, but Mendoza went into cardiac arrest and died before they arrived.

The farm's legal representation said in a statement to the BBC that it takes the health and safety of its workers "very seriously" and is contesting the labour department's findings.

"Many of the team members have been returning to Barnes for years, and returned again for this growing season, because of the farm’s commitment to health and safety," they said.

But Hugo did not return. He says he now works for a welding company.

“Bad things happen to a lot of us,” Hugo says. “I know it could happen to me, too.”

The agricultural industry also has the highest rate of workplace deaths, followed by transportation and construction, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, external.

Earlier this year, back-to-back deaths highlighted some of these dangers.

Six Latin American workers died in Baltimore when the bridge they were repairing overnight collapsed in late March.

Weeks later, a bus carrying Mexican farm workers to the fields crashed in Florida. Eight were killed.

Speaking at the Democratic National Convention, Maryland Governor Wes Moore recalled the Baltimore incident, honouring the workers who died “fixing potholes on a bridge while we slept”.

Both Mendoza and Hugo had H2A visas that allowed them temporarily to work in US agriculture. And the number of foreign-born workers who rely on this type of visa has grown.

Between 2017-2022, H2A visa holders have increased by 64.7%, or by nearly 150,000 workers.

In total, about 70% of farmworkers are foreign born, and over three-quarters are Hispanic, according to the National Center for Farmworker Health.

“Immigration is the key source of workers for many jobs in the US,” Chloe East, a University of Colorado Denver economics professor who focuses on immigration policy, says.

“We know for a fact that foreign-born workers are taking these types of dangerous jobs that US-born workers don’t.”

A 2020 federal investigation, external into agricultural H2A labourers in Florida, Texas and Georgia described conditions akin to “modern-day slavery”. Due to the investigation, 24 people were charged with trafficking, money laundering and other crimes.

“The American dream is a powerful attraction for destitute and desperate people across the globe, and where there is need, there is greed from those who will attempt to exploit,” Acting US Attorney David Estes said in a press release at the time.

Migrants that enter the country illegally can have even less protections if they’re hired to work, experts say. And almost half of agricultural workers are undocumented, according to the Centre for Migration Studies.

“Undocumented immigrant workers are concentrated in the most dangerous, hazardous, and otherwise unappealing jobs in US,” according to an article published in the International Migration Review., external

Could Trump really deport one million immigrants?

- Published18 November 2024

Democrats try to turn tables on one of their biggest weaknesses

- Published22 August 2024

Extortion and kidnap - a deadly journey across Mexico

- Published19 April 2024

One of the most dangerous jobs in the agricultural industry is dairy farming.

The dangers include overexposure to poisonous chemicals or hazardous machinery. Manure pits pose the risks of deadly toxic gases and drowning. The animals themselves can also be a threat.

Olga, who moved to the US from Mexico as a teenager, is an undocumented migrant dairy farm worker in Vermont. She says she saw her sister nearly trampled to death by a cow.

“The cow basically stomped on her and she was basically dying. Her tongue was even out,” Olga recalls.

Olga says that although the incident left her sister with a broken arm and two broken ribs, the farm’s manager demanded her return to work almost immediately.

It wasn’t until she provided a doctor’s note showing that her sister couldn’t work that “the boss left her alone”, Olga says. Her sister no longer works in farming.

Olga, however, still does.

The 29-year-old says she’s there “12 hours a day, every day”.

“There’s no raises. There’s no rest, and they don’t even pay on time,” she says. “They pay you when they want.”

Earlier this summer, the US Department of Labor implemented new rules designed to make working conditions for temporary farm workers safer, including protecting workers that organise to advocate for their rights from employer retaliation, and prohibiting employers from withholding workers' passports and immigration documents.

But just as authorities have tried to crack down on migrant abuse, anti-migrant rhetoric, fuelled by political debates over record-breaking levels of illegal immigration across the US-Mexico border, have added to Hispanic migrants’ difficulties.

On multiple occasions, Donald Trump has referred to illegal immigration as an “invasion” and called those who cross “animals”, “drug dealers”, and “rapists”.

“It makes me feel sad. We’re always being attacked for being migrants,” Olga said.

“They should see how we live to survive in this country.”

Enhanced border restrictions, enacted by President Joe Biden in June, may also make safety conditions worse, Prof East said, noting how stricter immigration laws can make workers afraid to speak up for safety protocols.

“Most people stay quiet because they are scared of all the laws being passed,” Hugo says. “You can’t complain.”

Hugo says lately he has noticed more discrimination, recalling a recent experience where a store owner refused to sell him water because he struggled to speak English.

“People treat us badly,” he says.