The screen tech that can do almost anything

It might look basic - but could this be the future of screens?

- Published

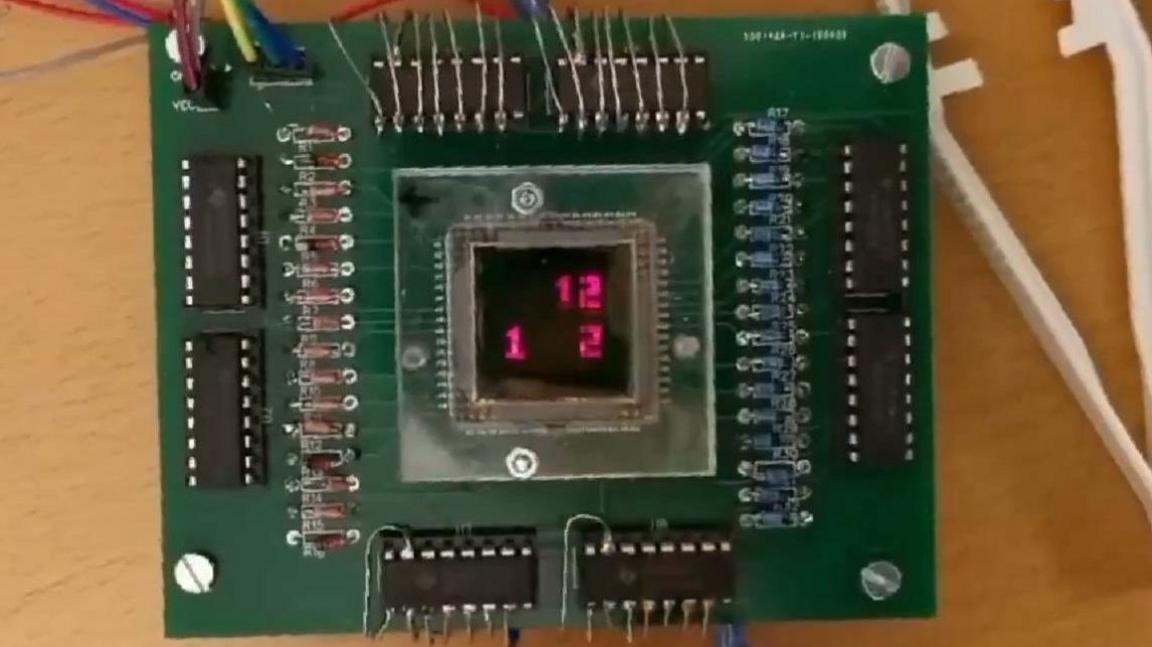

At first glance, it looks like a relic from the 1980s. A tiny computer screen with flickering, low-resolution text scrolling across it. But this could be the future.

The screen was made using perovskite light emitting diode (PeLED) technology. It is radically different to the LED technology used in your smartphone display today, and it could lead to devices that are thinner, cheaper and have longer battery life.

Not only that, PeLEDs are very unusual in that they can absorb light as well as emit it, meaning you can use the same material to integrate touch, fingerprint and ambient light-sensing capabilities, says Feng Gao at Linköping University in Sweden.

“This is difficult but we think it’s possible."

In today’s smartphones, such functions are carried out by electronic components separate to a phone’s screen itself.

In a paper published in April, external, Prof Gao and colleagues demonstrated their prototype with touch and ambient light sensitivity already working.

“It’s a very nice demonstration… it’s very new,” says Daniele Braga, head of sales and marketing for Fluxim, a technology research firm in Switzerland. Though he notes that optimising all the different functions promised here might make it difficult to commercialise this kind of display quickly.

Via video call, Prof Gao shows off the latest version of the technology. It is another small screen, but this time the pixels per inch (ppi), a measurement of the sharpness of the display, has been nearly doubled – at 90 ppi.

On the screen, a simple animation plays, showing two stick figures fighting. A paper with further details about this prototype has just been published, external.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Perovskite the mineral contains calcium, titanium and oxygen arranged in a crystal structure. It was discovered in the 1800s, but people later realised that they could make other kinds of perovskites that shared the same structure while having different elements or molecules as the components.

Depending on the materials chosen, perovskites can be really good at, for example, conducting electricity or emitting light.

“By slightly tuning the chemical composition you can cover the full visible spectrum,” says Dr Braga, explaining that making perovskites is a relatively simple and cheap process. “If you think about mass production, this is gigantic.”

There are some problems, though.

PeLEDs are notoriously unstable – they go bad with exposure to moisture or oxygen, for instance. Loreta Muscarella at VU Amsterdam, a university, is working to develop new kinds of PeLEDs.

She says that if you leave a PeLED lying around for a few hours or days, the colour of light it emits will gradually degrade or shift to a less pure version of, say, green, than the green you want.

And this undermines the whole point of perovskites. They are desirable in part because they can be tuned to emit a very specific, very pure form of red, green or blue – the key hues required for full colour digital displays.

More Technology of Business

Could brain-like computers be a 'competition killer'?

- Published18 June 2024

The battle for Gen Z social shoppers

- Published14 June 2024

'Insane' amounts of data spurs new storage tech

- Published12 June 2024

To keep them stable, PeLEDs can be encapsulated in glue or resin, says Prof Gao. But researchers are still working on ensuring that the technology does not falter over a long period.

Dr Muscarella says that traditional LEDs have lifetimes of 50,000 hours or more whereas PeLED lifespans are still in the hundreds to thousands of hours range.

It could be years before you buy a commercial product that contains a PeLED, she adds.

But there’s a different type of light-emitting perovskite that you might see on the market first.

It relies on photoluminescence. This isn’t an LED as such but rather a filter or film-like material that absorbs and re-emits light in a particular colour.

In some TV’s on the market today, a coloured filter supplies the crucial red, green and blue colours used in every pixel on the screen.

It’s by mixing those colours at different levels that you can get the range of hues required to display a full picture.

The red, green and blue filters are lit up by an LED backlight. But today’s filters actually block a lot of that light.

Photoluminescent perovskites, in contrast, let almost all the light through, which would mean a big increase in brightness and efficiency.

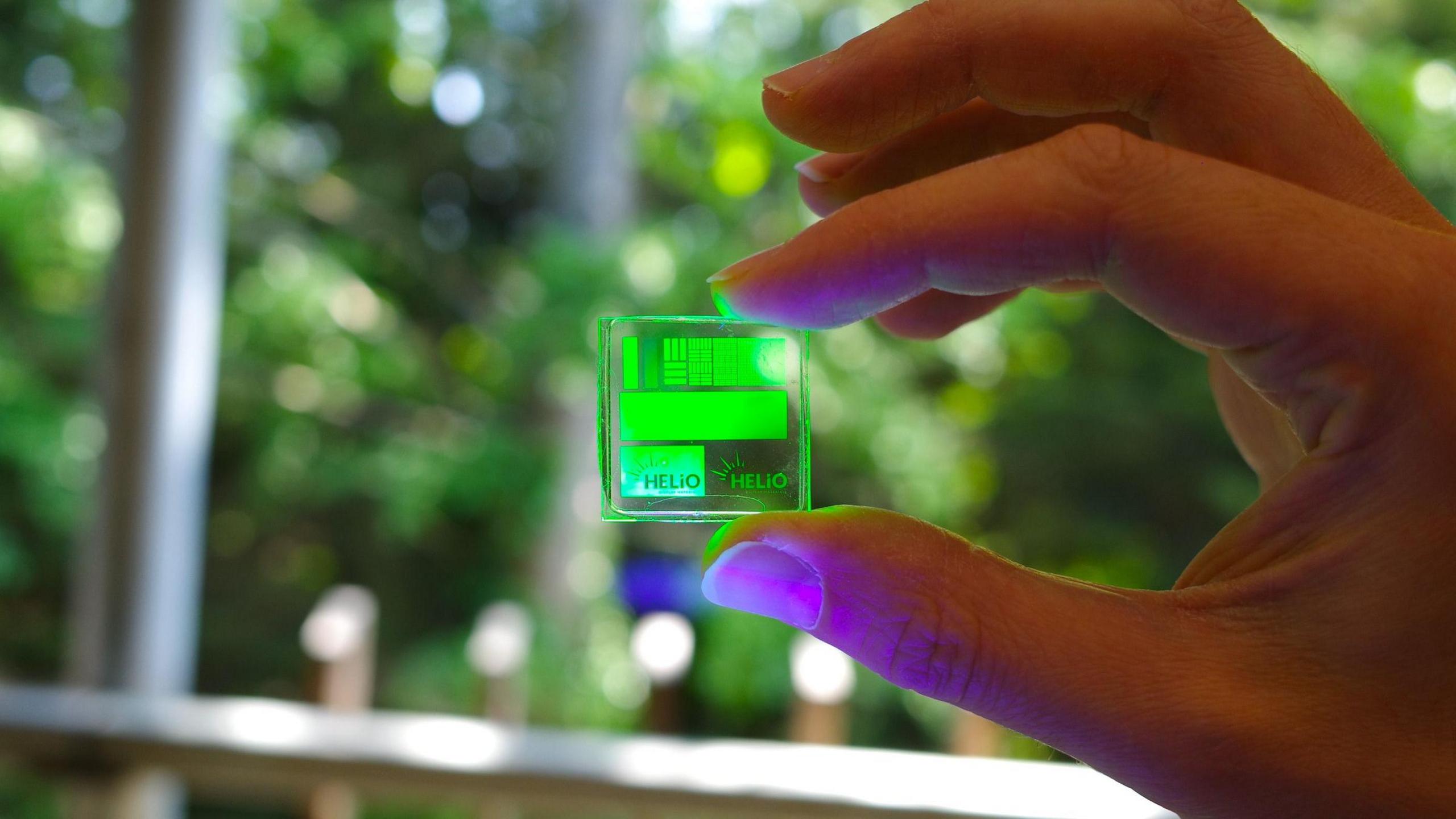

Helio, a British company, is working on this. A video on their website shows how a red or green coloured perovskite film can re-emit blue light as either red or green almost perfectly.

Helio's film can re-emit blue light as either red or green with little light loss

The technology Prof Gao and his colleagues are developing is quite different. They are experimenting with screens that emit light using LEDs which are themselves made with perovskites.

These are known as electroluminescent perovskites. Working with them is tricky because they are sensitive to electrical fields and, as mentioned, aren’t very stable. But eventually they could be even more efficient options for lighting up the red, green and blue pixels in a smartphone, tablet or TV screen without any need for colour filters at all.

The main advantages of switching to this technology could be in lowering the cost of these devices and in reducing their energy consumption.

No-one is quite sure how much less energy a future PeLED display might consume versus, say, an OLED screen, but lab experiments suggest that PeLEDs are already competitive with OLEDs and could one day significantly exceed them in terms of efficiency, says Dr Muscarella.

Prof Sir Richard Friend, at the University of Cambridge, is one of the co-founders of Helio, along with Prof Henry Snaith at the University of Oxford. He points out that one of the challenges with PeLEDs is in getting them to emit light in the right direction. This really matters for displays.

“You need to get light emitted in the forward direction rather than getting stuck going sideways,” he explains.

Researchers are experimenting with many different techniques to address this problem. Dr Muscarella and colleagues have tried imprinting a bumpy nanoscale pattern, external on the surface of PeLEDs, for example, which appears to improve light emission.

For Prof Gao, however, who has published alongside Prof Sir Friend and who received his PhD from the University of Cambridge in 2011, the promise of PeLED screens that do so much more than emit light is beckoning.

From fingerprint verification to heart-rate sensing and light detection, it could all one day be done using single slab of layered materials with the all-important light-absorbing perovskite in the middle.

“It’s really very unique,” he says, enthusing. “This is not possible with other LED technologies.”