How the art world adopted Glasgow 'Slum Boy' Juano Diaz

Grace Jones features in Juano's work

- Published

Juano Diaz has spent the past two decades establishing his name in the worlds of fashion, art and music.

He’s collaborated with a number of designers and artists, including Gilbert and George, Pierre et Giles, and David La Chappelle.

His own work combines digital images and painting and has featured Madonna, Grace Jones and Pharrell Williams.

But it’s a world away from the one he grew up in, as he explains in his memoir Slum Boy.

Born in Glasgow in 1977, he never knew his father beyond the name on his birth certificate.

His mother was an addict, who frequently abandoned him and he was taken into care at the age of four.

Juano's work combines digital media and painting

What was the children’s home is now a private house, but the owners agree to let John/Juano look inside for the first time in more than 40 years.

“It looks so small now, but I suppose I was so much smaller,” he says.

A huge stained glass window dominates the staircase, with figures representing art and industry.

“That room there was my bedroom. I must have passed it every day and I don’t remember it.”

“It’s a lot to take in. A lot of dark things happened here, but some nice things too, and of course this was where I was adopted. That changed everything.”

John’s new family were from the Romany Gypsy tradition. His grandmother claimed a direct connection to Charles Faa Blythe, the last king of the Gypsies in Scotland.

“My grandmother was a fantastic storyteller and I try to bring a wee bit of that into my art. I’m proud of the people.

"They took me into their home and they loved me like one of their own people and there was no judgement, no separation. I had the most gorgeous childhood.”

Juano was taken into care at Glen Rosa children's home

But the happiness was shattered by the death of his adoptive mother in a car accident.

As a young, mixed race, gay man, he struggled with his identity. Glasgow's Kelvingrove art gallery offered a haven and a source of inspiration.

There were two paintings in particular. Christ of St John of the Cross by Salvador Dali and A Highland Funeral by Sir James Guthrie.

“I could see my father in that picture, turning his hat in his hands at my mother’s funeral,” he says.

“But most of the time, I’d just sit in an alcove making portraits.

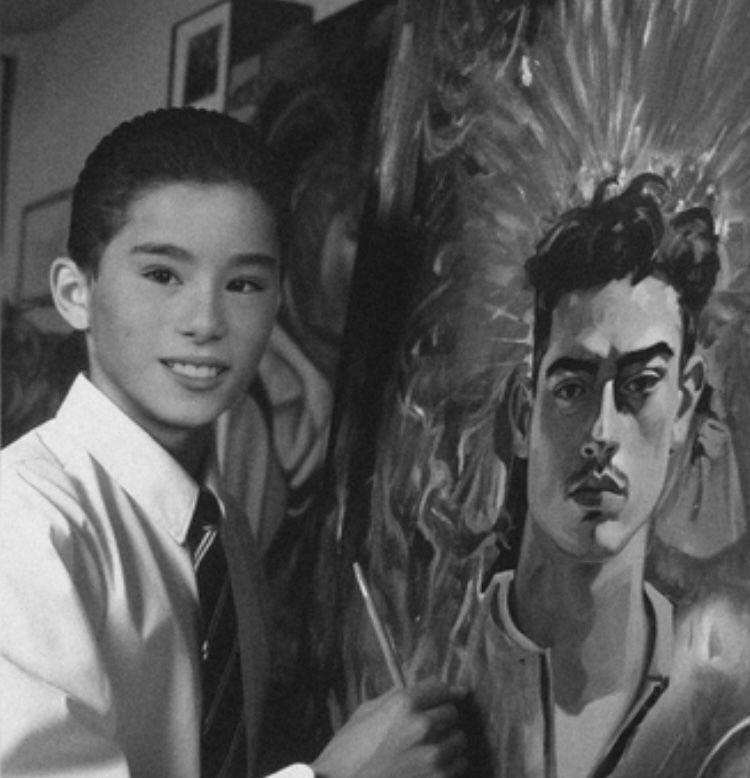

“I knew I wanted to be an artist from when I was a wee boy.

"I think being an adopted person, portraiture became really important to me because I wanted to hang onto people’s faces I’d been separated from.

"So I’d just draw faces over and over and over again.”

As a young boy Juano would paint faces over and over again

Attempts to get into art school failed, so he moved to Paris where he modelled for the French art duo Pierre et Giles and the late Thierry Mugler.

It was there he reclaimed his name from his South African father.

“When I started to work with Pierre et Giles, people would say what should we call you?

"That’s when I said I’m Juano. That’s the name on my birth certificate, it was only changed through adoption so I reclaimed it. “

He began to make his own art, which draws on his diverse heritage. A selection of the pieces layer paint on digital images of real people.

It has been exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art and the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York. And on at least one occasion, the subject has asked to buy the work.

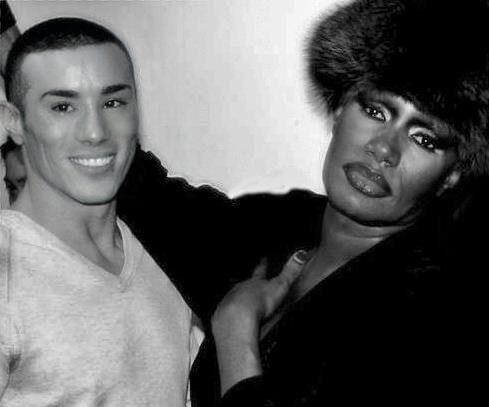

“I got a phone call from the son of Grace Jones who had seen my work on a website and called to ask if it was for sale. I said it was, and he asked if I could bring it to London that day. So that evening, I found myself in Grace Jones’s dressing room at the end of her show.”

Madonna is one of the many celebrities to feature in Juano's work

Grace not only bought the work, she’s become a family friend.

“I took my son to meet her last year with my partner. We hadn’t had a chance because of the pandemic. She absolutely loved him. When we were leaving, she said, tell everyone I’m your art godmother. It was such a surreal moment. “

Juano says he began writing his memoir a decade ago but didn’t plan to publish it.

“It was more of a cathartic thing. And it was emotional because I was looking through 200 pages of social work records, everything down to the food I’d eaten. I’d no intention of writing a book but it happened.”

Andrew O’Hagan read an early draft and sent it off to a publisher. He originally intended to call it Lucky Boy but it’s been retitled Slum Boy.

Juano with Grace Jones, now a close friend

“I was being ironic but I have had a really lucky life. It could have been so different if I hadn’t been adopted. I don’t even know if I would have been here.”

“When they suggested Slum Boy I said no, we can’t call it that. That’s completely derogatory and then I sat with it and realised it works.

"The publisher said look, if anyone can wear that title, it’s you. What were your conditions as a child, living with your mother. I said it was a slum.

"There was no glass in my bedroom window. It was cold, it was damp, it was a slum.”

He says he’s tried to tell his story through art – but always failed.

“It just seemed too dark and I don’t like dark art. I like to celebrate things that are magical and bright and colourful.”

But writing the book has encouraged him to explore his own story. He is currently working on a series of paintings based on documentary maker Nick Hedges’ photographs.

But he says he’s glad to end each day with his partner and son in a warm and happy home.

Slum Boy: A Portrait is published by Brazen Press on Thursday 29 February.