BBC India reporters on why some voters said no to Modi

What worked for India's Modi and what didn’t?

- Published

When Narendra Modi set his sights on a barnstorming victory - 400 out of 543 seats for his alliance - few scoffed at the ambition.

After all, the Indian prime minister and his BJP have been a largely unstoppable force since coming to power a decade ago.

But while Mr Modi and his alliance are on course to win a majority, it is not quite the untouchable win he and his allies envisioned when counting began this morning.

Below, BBC correspondents in India give their thoughts on why we arrived at results few expected - and what it could mean for the world's largest democracy going forward.

Questions over use of 'Hindu card' as a campaign tool

Religion is a factor in every Indian election, and this one was no different.

Mr Modi inaugurated a Hindu temple at a controversial site that had been disputed between Hindus and Muslims in January and this was expected to give his party a big boost during the election.

But no one quite expected the BJP’s campaign to be as polarising as it was - or for some of the most aggressive comments to come from the very top.

At a campaign rally in April, Mr Modi said: “When their (the opposition Congress) government was in power they had said Muslims have the first right on the nation’s wealth. This means they’ll collect the wealth and give it to whom? To those who have many children. To infiltrators.”

Some analysts interpreted the remark as an attempt by Mr Modi to galvanise his conservative Hindu support base.

But looking at the results from some key constituencies – the BJP candidate has lost in the temple city of Ayodhya - it doesn’t appear to have had the desired effect.

Questions are now being raised about using the Hindu card as a campaign tool, especially since what it seems to have achieved is the opposite - uniting Muslim minorities against the BJP.

Yogita Limaye, BBC News in Delhi

'Brand Modi is beginning to fray'

Marketing consultants have attributed Narendra Modi’s enduring popularity to his mastery of branding, transforming routine events into spectacles and astute messaging.

“He strikes a deep chord with his aura of clarity and strength, speaks simultaneously to anxieties and aspirations, communicates using emotionally resonant metaphors, understands the power of branding key initiatives to generate a sense of activity and purpose and knows the power of enigmatic silence,” Santosh Desai, a well-known brand consultant, wrote in 2017.

Over the years, Mr Modi also sold himself as a cultural icon engaging a diverse people both at home and abroad, cementing his status as an influential leader in Indian politics. A weak opposition and a largely friendly media helped him build his brand. “He’s pop culture in 70% of this country,” a brand consultant said at a conclave last year.

No longer. As results of the general elections show, Brand Modi is beginning to fray. Mr Modi has never underperformed and won less than a majority in all the elections he has fought so far.

It has been different this time. Tuesday’s results show that some of the sheen may be wearing off and even Mr Modi is not immune to the vagaries of anti-incumbency.

Soutik Biswas, BBC News in Delhi

4,200 mile opposition march 'galvanised party cadres'

Since the July 2023 formation of the opposition INDIA alliance, a grouping of more than two dozen parties, the Modi-led government has been painting it as a ragtag bunch of self-serving leaders out to personally target Mr Modi and destroy the country.

While the leaders of the ruling BJP, along with most analysts and pollsters, had for months been predicting an easy win for Mr Modi, the Congress-led opposition block kept emphasising rural distress, inflation and rampant unemployment in its messaging and public meetings.

"The Constitution is in danger" and the country’s “democratic institutions are under attack” under a “divisive” Mr Modi was their war cry.

A 4,200 miles (6,700 km) long march by Rahul Gandhi, a senior leader of the Congress party, that began months before the elections was heavily panned for its timing, but analysts believe it enthused supporters and galvanised party cadres.

The opposition also upped its social media reach and aggressively took on the BJP which has for a long time dominated the digital landscape in India.

Vineet Khare, BBC World Service in Delhi

Welfare schemes of Modi rivals 'better connect' with voters in southern India

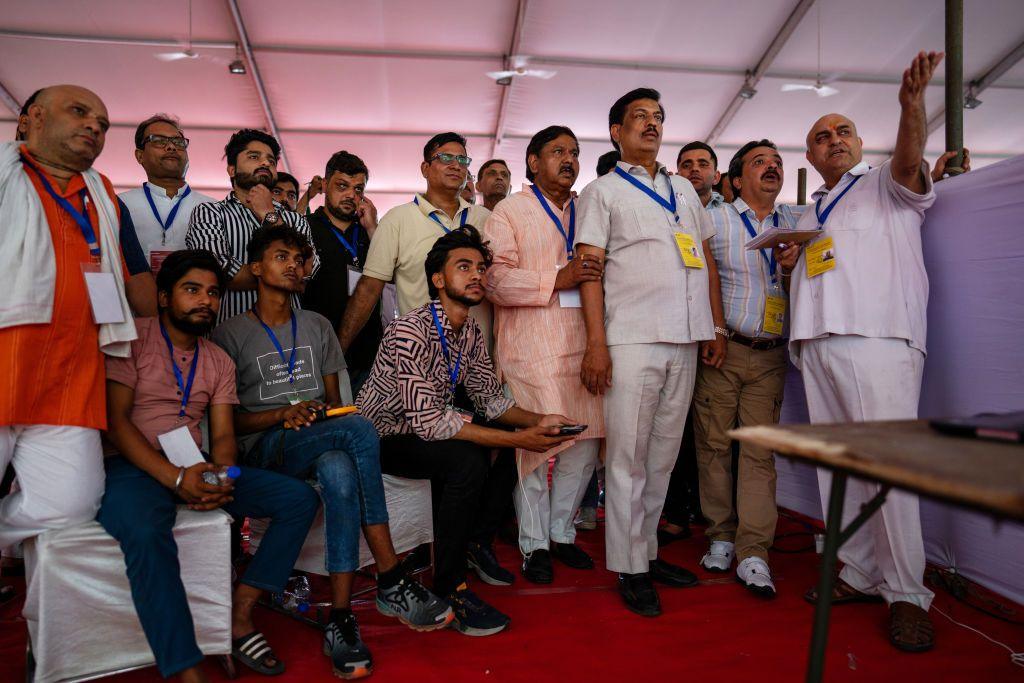

Election results were eagerly watched by millions across India

Mr Modi's BJP is still struggling to make a major impact in southern India, although its vote share is set to increase.

It won 25 seats in Karnataka alone in 2019. But this time it is losing at least 10 seats in the same state to the Congress party.

It is on the verge of doubling the four seats it won in Telangana and a couple of seats in Andhra Pradesh because of its alliance with the regional Telugu Desam Party, headed by the IT industry friendly Chandrababu Naidu.

In Tamil Nadu, the regional DMK led alliance is on the verge of repeating its 2019 performance of a clean sweep.

And in Kerala, the Communist government and the Congress-led front seem to have kept the BJP from the Lok Sabha.

In short, the development focused welfare schemes of the non-BJP parties appear to be making a better connect with the aspirations of the voters down South.

Imran Qureshi, BBC Hindi in Bangalore

So what next? Result may force Modi to 'slow down'

Mr Modi projected himself as the voice of the Global South – a leader who acted as a bridge between the developing and the developed world.

The Indian PM’s global heft was grounded in the massive support he had at home. He provided a sense of continuity to global leaders and alliances.

Mr Modi will now head a coalition government. He is likely to have bipartisan support on foreign policy, but he will have to take allies into confidence before taking crucial decisions that affect global politics.

FOLLOW LIVE: Shock for India's Modi as opposition set to slash majority

- Published4 June 2024

India's Modi heading for reduced majority, early results suggest

- Published4 June 2024

That might force him to slow down, and adopt a more consultative decision making policy.

So far India has defiantly practised its policy of strategic autonomy in foreign affairs, and that might not change.

But what will change is Mr Modi’s ability to take quick decisions on global affairs – something he often did without consulting his own allies or the opposition.

Vikas Pandey, BBC News in Delhi

Coalition government would be 'litmus test' for Modi

Modi supporters celebrate in his constituency of Varanasi

Be it as Gujarat state chief minister or as prime minister in his last two terms, Narendra Modi has run a full majority BJP government. Coalition partners did come along to give a hand, but the government’s future was never in their hands.

Current numbers clearly indicate the BJP is falling short of majority which means Mr Modi will seek support from allies. He has got used to running a centralised government and party under him which will have to change keeping the new reality in mind.

He will need to be a lot more mindful of the concerns and sensitivities of coalition partners and that doesn’t come easy to him, one analyst noted.

India is not new to coalition politics, but coalition governments are often prone to instability. So it would be a litmus test for both Mr Modi and the BJP over their adaptability to a changed scenario.

Nitin Srivastava, BBC World Service in Delhi