Is vertical farming the future of food production?

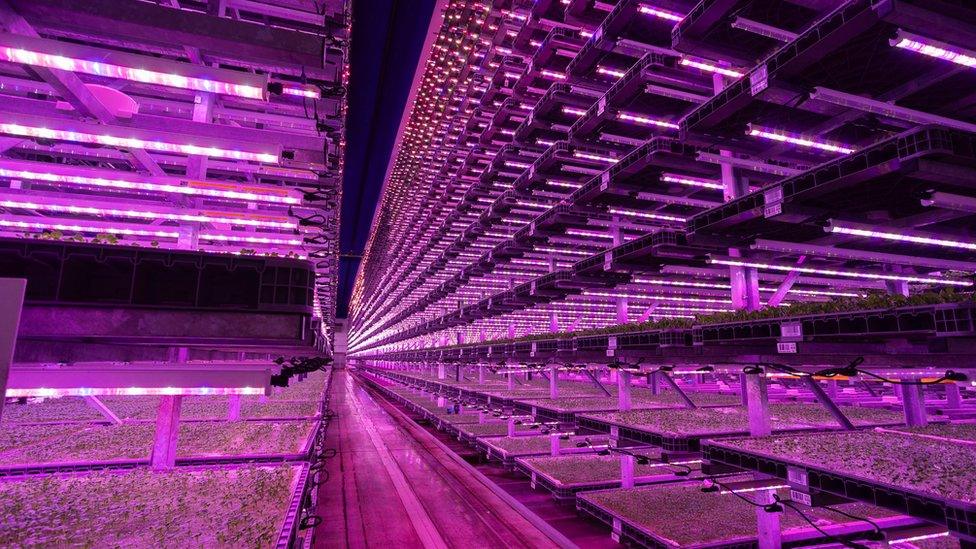

The crops are grown in layers under artificial light in conditions designed to mimic those found outside, but without any weather variables

- Published

A new method of growing food could "feed the world without trashing the planet at the same time", according to an alternative farming entrepreneur.

Vertical farming is the practice of growing crops - such as rocket, watercress, basil and chives - in stacked layers, which are subject to artificial temperature, light, water and humidity control.

Fischer Farms said at capacity it can supply 1,000 tonnes of leafy greens, herbs and salads a day from its site in Norwich using the method.

Belinda Clarke, the director of Agri-TechE, said vertical farming could be "a gamechanger for the industry", but it had "been really difficult to get the business model right".

Fischer Farms is designed to emulate "a Tuscan hillside, with the warmth of sun and slight breeze", said Samantha Woods

Tristan Fischer, the founder of Fischer Farms, said he believed the system could "provide a significant amount of food stability around the world".

"They're emulating wind and sunshine, so we can have a night cycle for the plants, the wind makes the plants stronger and the sunshine helps them to grow," said grow assistant Samantha Wood.

Mr Fischer believed vertical farming could "feed the world without trashing the planet at the same time".

Vertical farming could address concerns over global warming and a growing population, said Tristan Fischer who has been developing technology to make it commercially viable

"The very sophisticated systems are expensive, there's a lot of up front capital costs and you need a high value crop," said Dr Clarke.

To "justify the investment", investors would need to grow crops for pharmaceuticals or ingredients for cosmetics or crops the UK currently imports out of season.

Dr Clarke suggested cereals, which "we're quite good at growing to scale under free sunlight", would be harder to justify.

The company has trialled growing wheat and plans to move on to growing fruit followed by soy, wheat and peas.

The crops are grown in a biosecure atmosphere, without pesticides, herbicides or insecticides.

The seeds are germinated in the dark and then moved to grow under bright lights in in conditions of 24C (75F)

Fischer Farms' four acre (1.61 hectare) Food Enterprise Park unit produces the same amount of food as a traditional 1,000 acre (404 hectare) farm, according to the company.

It also said the farm, which is funded by private equity firm Gresham House, is one of the biggest in the world, at 25,000 sq m (269,098 sq ft).

The system does require a great deal of energy.

Dr Clarke said this means vertical farming can only be commercially viable if it is built near a suitable energy source, such as a solar farm or an anaerobic digester.

Fischer Farms, which already uses existing solar panels on the farm's roof, plans to address its future power needs by using energy generated from a 130-acre (52-hectare) solar farm about to be built next door.

Follow Norfolk news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp us on 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published23 May 2024

- Published29 May 2024

- Published20 February 2024