Why do doctors across the world use the Glasgow Coma Scale?

Paramedics use the Glasgow Coma Scale to assess patients' responsiveness

- Published

How do you tell if someone is in a coma? It might not sound like a difficult question.

But in the 1970s, two Glasgow neurosurgeons spent years developing a measure to solve this very problem.

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is now used in hospitals around the world and is often mentioned on TV medical dramas.

It all began when Sir Graham Teasdale and Prof Bryan Jennett sought their own method to evaluate consciousness.

“We became interested because head injuries were common and they weren't managed that well," said Sir Graham.

“Most of the scales had been invented by a consultant or professor using obscure language that only they understood.”

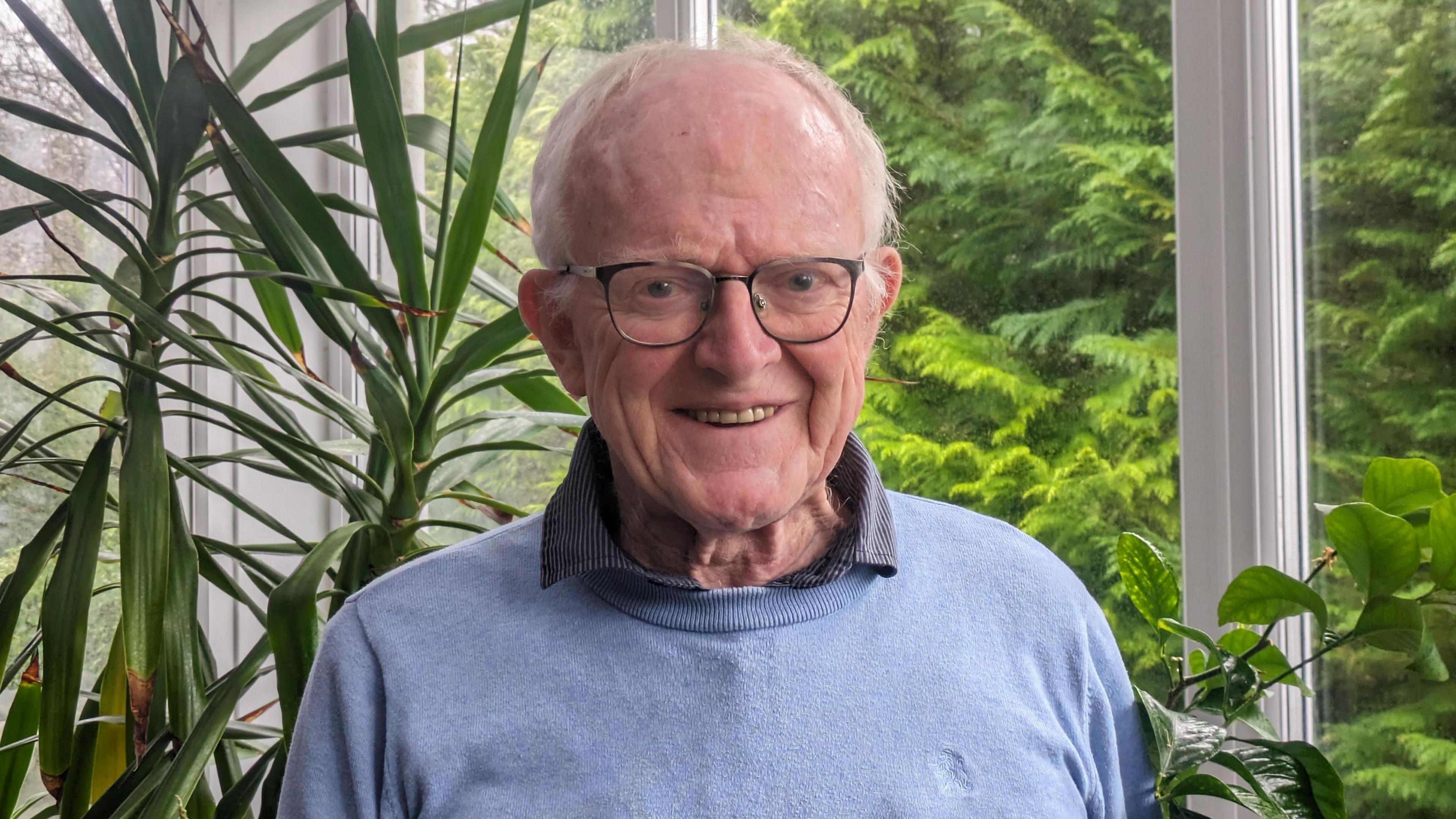

Sir Graham Teasdale created the Glasgow Coma Scale with his colleague in the 1970s

Sir Graham said previous methods were “hopeless” for communicating a patient’s condition between medical staff and detecting changes in their state.

“Sometimes even the same person couldn't remember how the patient was last time,” he said.

Sir Graham said medics commonly used terms like "stuporous" or "slow to come up" or "semi-comatose" - which would not convey anything real.

He began by looking at existing scales and realised there was overlap in the features being examined.

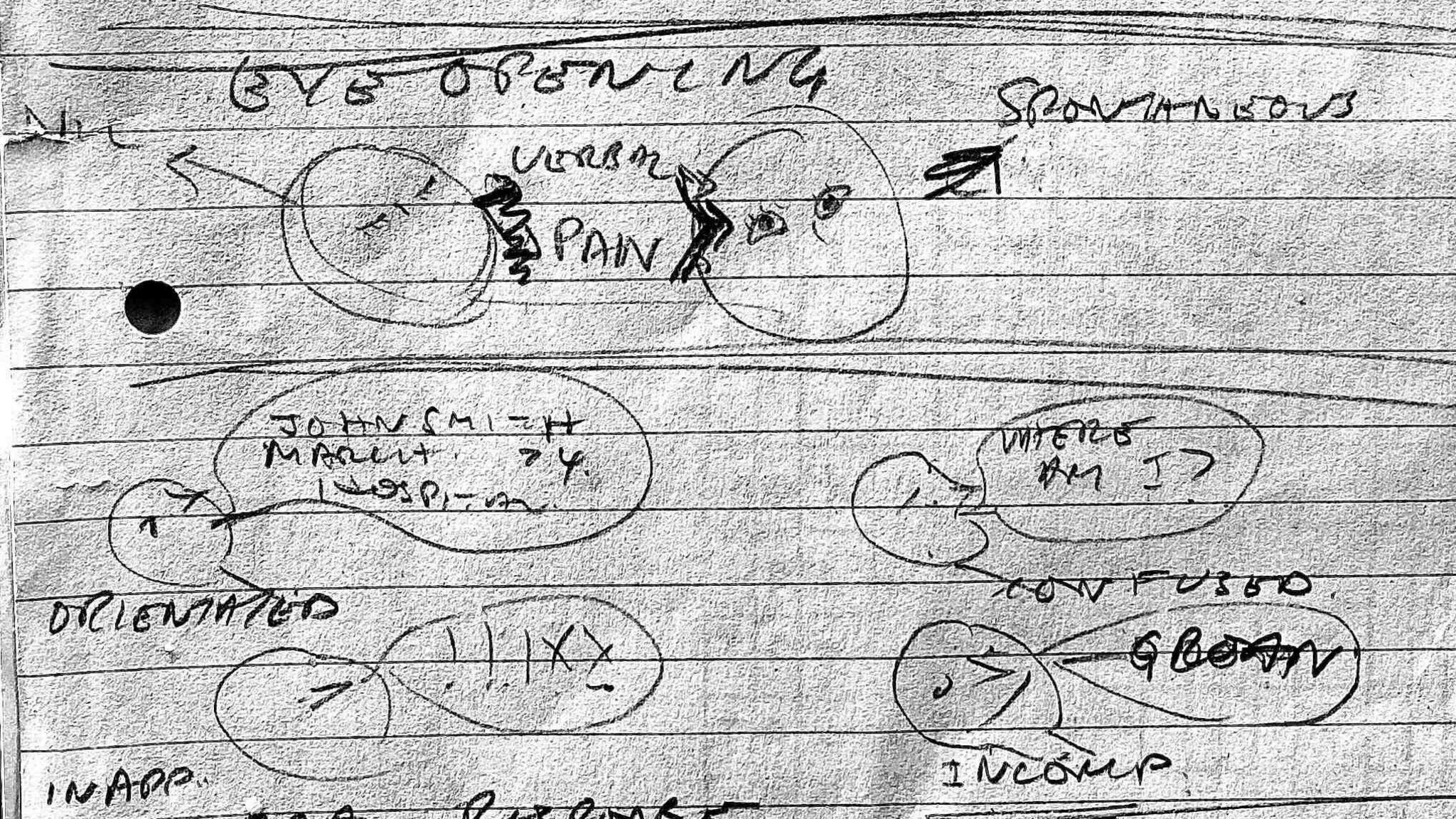

It was on this basis that eye opening, verbal response and motor response, external became the three measures that made up the GCS.

Sir Graham carried out studies with different medical staff, particularly nurses, at Glasgow’s Southern General Hospital who would examine the same patient and compare results.

“We honed down on some very simple, common English words to describe what we were looking for and simple techniques to list them," Sir Graham said.

The phrases used in the scale include “only moans/groans” and that a patient “correctly gives name, place and date”.

“The staff thought this was great because it meant that what they were doing was working far more than it had in the past," he said.

An early sketch of the Glasgow Coma Scale showing eye opening as a measure of consciousness

After two or three years of using basic language to communicate patients’ conditions, the GCS developers experimented with adding three scores together into a single summary score.

It was thought a single score would be valuable to communicate quickly and "relay findings to the room".

“We did something that the statisticians would raise their hands at in horror,” said Sir Graham.

“We simply gave each of the steps in the scale a number and added them up - to everyone's surprise, it worked very well.

“The highest score is 15, which means the person's awake, they know where they are and are obeying commands.

“And the lowest score is three, which means no eye opening, no speech and no movement.”

Sir Graham Teasdale and Prof Bryan Jennett developed the GCS together

Sir Graham developed his interest in head injuries and neurosurgery before he worked in Glasgow.

Born in County Durham in 1940, he had studied medicine at Newcastle.

After graduation he worked in neurology in Birmingham then came to Glasgow to gain his surgical fellowship.

Sir Graham met Prof Jennett, who offered him a role in Glasgow’s newly opened Institute of Neurosurgery.

Prof Jennett, who died in 2008, was a leading figure in neurosurgery and was made a CBE in 1991.

Sir Graham says the Glasgow Coma Scale was created through a collaborative effort between the two men.

“It wouldn't have happened without the two of us,” he said.

And he says calling it the Glasgow Coma Scale was a huge part of its success.

“I can recall we sat in Bryan's office saying should it be the Jennett-Teasdale scale or the Teasdale-Jennett scale.

"We decided no, it would be the Glasgow scale, therefore other people won't feel they're being slighted by using it.

“It took out that competitiveness that neurosurgeons had. I think that was a very wise decision.”

Severity of injuries

After developing the scale in Glasgow, it was first used in partnership with hospitals in Rotterdam, Groningen and Los Angeles to confirm its wider value.

Data was collected on patients both in the first days after a head injury and at a follow up six months later.

Although the severity of injuries and the method of treatment changed between locations, there was a relation between the findings of the scale and the outcome in each case.

Sir Graham said there was “a quiet progression” until 1978, when US medical journal Neurosurgery said the GCS should be adopted throughout the world.

“That was really a very good endorsement,” said Sir Graham.

References to the GCS being used have increased steadily over time. It is now a part of data required by the World Health Organisation.

In 2018, the scale was updated to incorporate the reaction of a patient’s pupils to light.

The coma scale is key decision-making around prioritisation of patient care

Prof David Lowe, consultant in Emergency Medicine at Glasgow's Queen Elizabeth Hospital said the scale had given the city “world-wide recognition”.

He said: “It's used by paramedics each time we get a standby call and is integral to each subsequent assessment, allowing clinical teams to enhance detection and response to deterioration.

“From stroke to infection, they will report a GCS as part of their initial assessment and it remains a key driver for our decision-making around prioritisation of care."

The scale has been translated into 60 different languages and has featured in many TV medical dramas, including Casualty and Grey's Anatomy.

It was even named on TV motoring series The Grand Tour, where host Jeremy Clarkson said the GCS was one of Scotland's most important inventions.

“We did a survey back in 2014," said Sir Graham.

"We asked 80 units throughout the world and said, ‘Are you using the Glasgow Coma Scale or not?’

"Everyone was.”