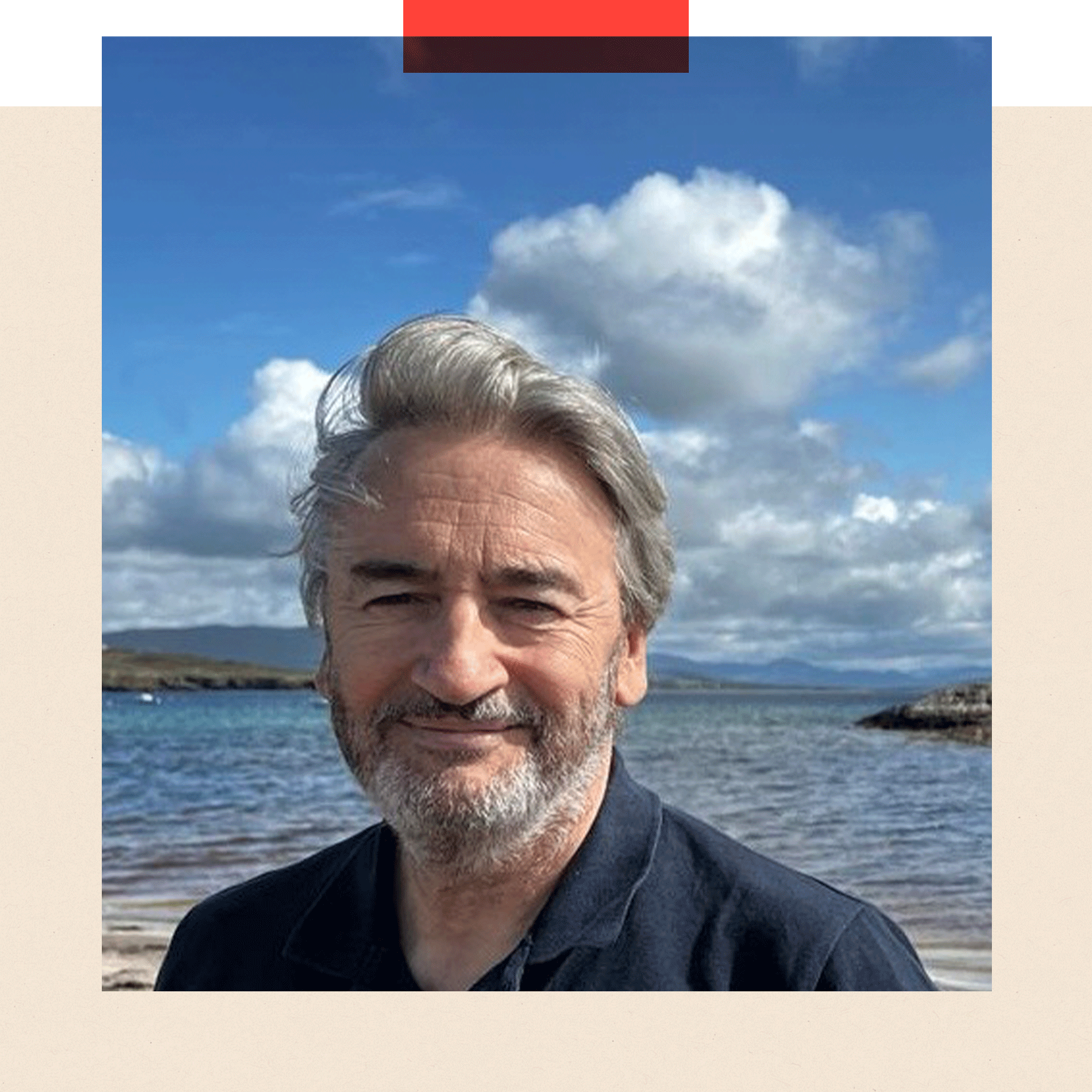

In a powerful personal account, Fergal Keane reflects on living with PTSD, depression and his search for balance in life. What he has discovered along the way is a deeper study of happiness that can apply to those with serious mental health challenges, but also to those simply in need of a lift.

Listen to Fergal read this story

There was a moment, nearly two years ago, when the change inside hit me with force. I was walking with a loved one on the eastern edge of Curragh beach in Ardmore, County Waterford, a place of warm refuge since I was a child. We paused beside a river that flows into Ardmore Bay. I was listening to the different sounds the water made - the swift rush of the river, the surf crashing on the shoreline.

Suddenly there was the sound of air being displaced by dozens of wings. A flock of Brent geese came sweeping over the cliff, riding the wind towards the sky. I felt a lightness inside, and such gratitude that I laughed out loud.

"So, this is how it feels," I thought.

To borrow and turn around the words of the novelist, Milan Kundera, I felt a wonderful "lightness of being".

Fergal Keane: 'Not long before that day of the beautiful geese, I had come out of an emotional breakdown'

That moment came back to me this week. I was thinking about the Blue Monday phenomenon - the January day that is said to be the saddest of the year.

As anyone who knows clinical depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) will tell you, there are no specific days of the year for sadness. It can be the brightest day, in the loveliest place, and you still feel like your mind is trapped in permafrost.

But Blue Monday did prompt me to reflect on happiness. What is it anyway? What does it mean in my life?

Grey days and dark nights

Not long before that day of the beautiful geese, I had come out of an emotional breakdown. It was March 2023, and I felt as if I had gone 12 rounds with a heavyweight prize-fighter. But the person I'd fought was myself. As I had done for decades.

I had experienced several hospitalisations over the decades, stretching back to the early 90s. I fought a relentless battle with shame, fear, anger, denial - all these things that are the opposite of happy. There were grey, terrifying days. Every branch bare, even in deep summer. And nights waking drenched in sweat, waking to obsessive rumination, bad dreams leaking into the dawn.

Add in recovery from alcoholism at the end of the 90s, and I've done plenty of research into the dark nights of the soul.

Fergal today: He has written books and created documentaries about mental health

By the time of the 2023 breakdown I had gone past the point of hoping for happiness. In those days I would have settled for a little peace of mind. In 2019, I had stepped back from my job as the BBC's Africa Editor due to my struggles with PTSD.

Two years later I wrote a book on the subject and made a television documentary for the BBC. Yet, even after all that, I experienced another breakdown.

The science of happiness

Professor Bruce Hood, of the University of Bristol, speaks of the human tendency "to blow things out of proportion…[focusing] on our own failings or inadequacies". He runs ten-week courses at Bristol on the science of happiness and talks about the need to find balance because, as he puts it, "our minds are biased to interpret things very negatively".

This certainly resonates with me. A caveat, however: Professor Hood's area is addressing feelings of general low wellbeing, and he's clear that focusing on the science of happiness will not necessarily be a cure all for someone with a condition such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) .

I have a specific diagnosis. In 2008 doctors first told me I had PTSD based on multiple instances of trauma as a war reporter, but also rooted in the circumstances of childhood in a home broken by alcoholism. Depression and anxiety were both major parts of that condition. As was addiction to alcohol. I escaped also into the exhilarating energy, camaraderie, and sense of purpose that went with reporting conflict.

I would also stress that what works for me as I try to find happiness, may not definitely work for everyone else. There are specific mental health conditions that require equally specific treatments. With PTSD, a combination of therapies helped me greatly, along with the fellowship of others who had similar experiences.

Fergal pictured earlier in his career as a war reporter

Medication also ameliorated the physical symptoms of anxiety and hypervigilance. A dropped plate, a backfiring car could reduce me to a pale, shaking, sweating wreck in seconds. Likewise, the nightmares which could leave me thrashing in my sleep.

I am privileged. I have had access to the best treatment. There are so many in our society who do not. According to the British Medical Association more than one million people are waiting to access treatment. It's also important to recognise that there are numerous social, economic and cultural factors that influence our ability to experience happiness.

There is an ongoing study of genetic predisposition to depression and addiction. The World Wellbeing Movement (WWM), a charity promoting wellbeing in business and public policy decision-making, says that one in eight people in Britain live below what it called the Happiness Poverty Line – this is measured using data supplied by the annual reports of the Office for National Statistics, and based on the question – on a scale of 0 to 10: 'Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?'

The WWM describes the one in eight figure as "staggering" and says there are "worrying issues related to mental health [that] remain unaddressed and underfunded".

Having expressed my caveats, I hope there are things in my experience, the tools for recovery I have been generously given, that might help people who are struggling with the loneliness of depression or the turmoil of PTSD, or just struggling with the normal pain of life from time to time.

The secret to happiness is no secret

In my experience, the secret to happiness is that… there is no secret. It's out there in plain sight, all around us, waiting to be found. But it is not ever present. It is not the natural everyday condition of humanity; no more than depression or rage are.

As the American psychotherapist, Whitney Goodman, author of 'Toxic Positivity: How to embrace every emotion in a happy-obsessed world' puts it: "Anyone that is fixated on making you feel happy all the time is selling you snake oil in my opinion. It doesn't make sense. It doesn't work… telling people that they just need to be happy, to manifest different thoughts, I think it would have worked by now."

'In my experience, the secret to happiness is that… there is no secret. It's out there in plain sight, all around us' (Pictured: A large smiley face at an event at ExCel London)

I spent years sitting in therapists' chairs, and sometimes looking out the windows of psychiatric wards, hoping for the perfect cure that would fix my head and battered spirit.

For me loneliness was the defining characteristic of my mental health problems. I went deep into myself and found nothing to love or admire. I shut the door.

The answer didn't arrive in a blinding flash of light. If I could pick one thing that made the greatest difference - after I had been stabilised with treatment - it was, and always will be, work. Not the work that drove me to a near constant state of exhaustion as I chased scoops and prizes so vital to my insecure ego.

Note to all who get their validation from work: the workaholic is the most accepted addict of all. In fact, he and she are celebrated. Why would you want to change when the bosses and society applaud you? Work is the great permissive addiction.

Fergal speaking at an awards ceremony in 2016. In his article he writes: 'Work drove me to a near constant state of exhaustion as I chased scoops and prizes so vital to my insecure ego'

The work I am talking about is very different. Nobody will tell you what a brave, talented person you are for doing the work of real happiness. But you will feel it in the reactions of people you love, the gratitude of waking up without a sense of dread, the awareness of beauty around you. And knowing you will keep your commitments, and live as a person who doesn't just talk about caring for people but does their best to live that talk.

One night in hospital, in 2023, having been admitted with PTSD, I watched a documentary in which the American psychotherapist, Phil Stutz, spoke of three fundamental truths to be accepted by people struggling with mental health problems: that life can be full of pain, full of change, and that living with these things needs constant work.

I was exhausted from suffering. But I was also willing to do whatever work I could to find peace of mind. The happiness came later.

Returning to the simple stuff

What did I do? A lot of simple stuff at first.

I wrote a gratitude list every morning. My daily accounting of the good in my life. I read more poetry because it calms me down. I went for long walks with the dog by the River Thames and in Richmond Park. I even started to meditate - a miracle for a man who could rarely sit still for more than five minutes. I went to the movies more. I did simple domestic chores. Not the kitchen cameos of past days, but regularly cleaning, washing, cooking, paying the bills. Wonder of wonders, I could do it!

I made more time for friendship. And for love, of the people who mattered most to me. I listened where before I might only have pontificated. I worked very hard to shut up when someone wanted to express a resentment, instead of letting the childhood habits of defensiveness take over.

I offered to help others who were struggling. Those in recovery from addiction will know the maxim about sobriety: "To keep it you have to give it away." Likewise, happiness.

Helsinki from above: Finland is number one on the World Happiness Index

The Finnish philosopher, Frank Martela, from Aalto University, suggests acts of kindness as part of the solution.

As it happens Finland is number one on the World Happiness Index. "Connect with others and connect with yourself," he says.

"Connect with others through social relationships… doing good things to other people, contributing through your work or through small acts of kindness."

'You are stronger than you think'

There was a wonderful old friend of mine, Gordon Duncan, an addiction counsellor, who first alerted me to the fact that I had a lot of anger built up inside me, and that this drove my drinking and depression. We clashed a lot in the first weeks that we knew each other, but over time became the closest mates.

When he was dying in hospital, I visited one day, and saw that he had lapsed into a coma. Neither of us were particularly religious, but I whispered in his ear a prayer that was dear to us both:

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change.

The courage to change the things I can.

And the wisdom to know the difference.

I don't know if he could hear me. I suspect probably not. But I remembered something he used to say to me when I was heading down into the depths. "You're stronger than you think, son. Stronger than you think."

I pass it on to all who are suffering in their minds. For me, I know things can change fast. There are no guarantees. Of happiness or anything else. But I accept that.

More from InDepth

Rise of vaccine distrust - why more of us are questioning jabs

- Published16 January

'It's still in shambles': Can Boeing come back from crisis?

- Published28 December 2024

The American writer, Raymond Carver, who survived alcoholism to write some of the most beautiful poems about grief, and happiness, left a short poem before he died from cancer, aged just 50. It was his epitaph, and I think it sums up the whole quest for happiness.

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

I will wake tomorrow and be glad to open the curtains, and drink coffee and think of those I love who are near and far. And then I will get back to work, the real deep work that goes on every day.

Additional reporting by Harriet Whitehead

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.

Sign up here to receive our new weekly newsletter highlighting uplifting stories and remarkable people from around the world.