Lough Erne eel conservation work could help save endangered species

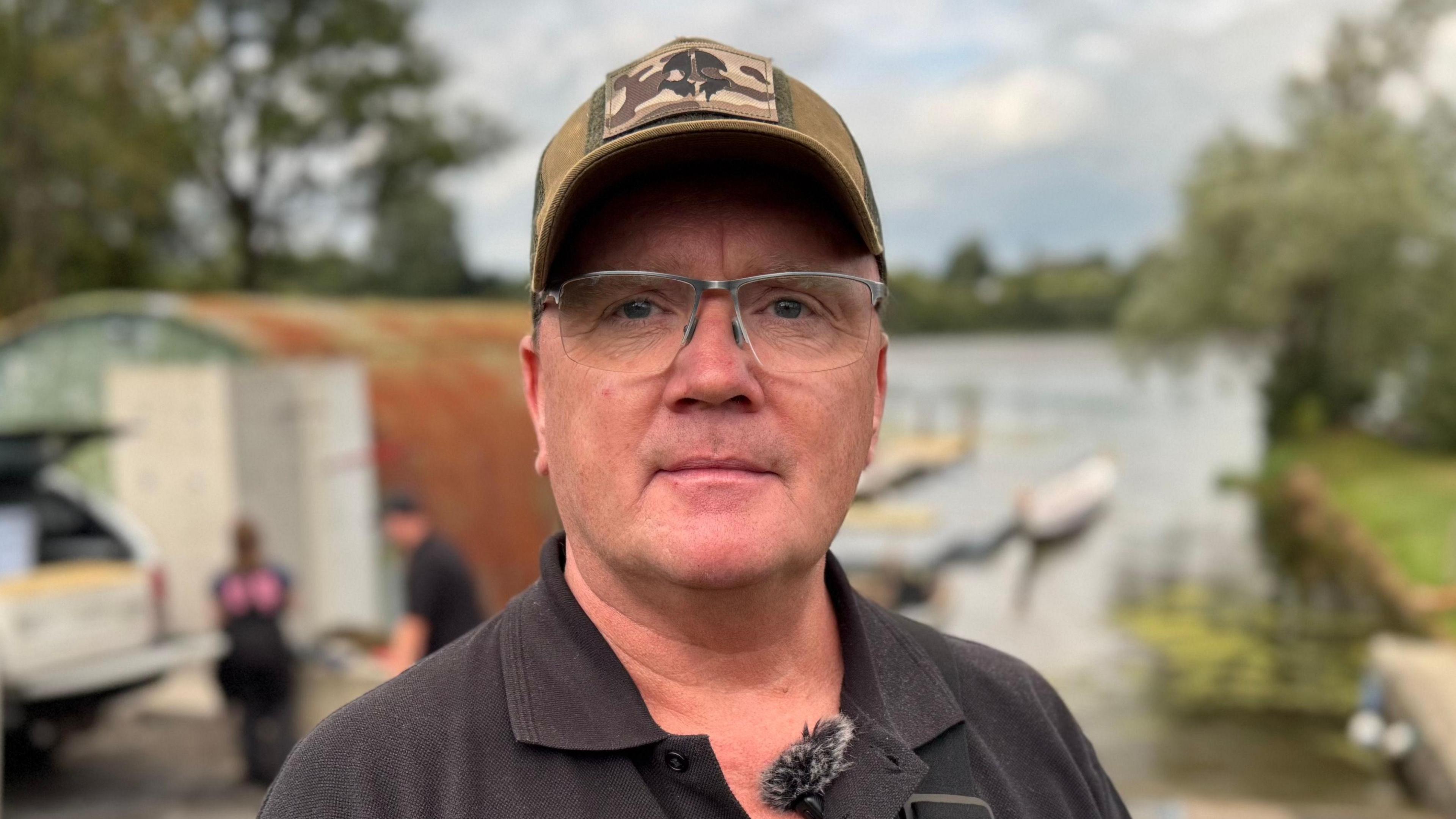

Dr Derek Evans is a senior fisheries scientist at Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute

- Published

Eels caught in Lower Lough Erne as part of a continuing trap and transport programme could be part of the species' salvation.

Commercial eel-fishing has been suspended on Lough Neagh - 70 miles from Lough Erne - but government-backed conservation work continues elsewhere.

The European eel is red-listed as critically endangered - it ranks one tier below the conservation status given to pandas, rhinos and tigers.

"Since 1983, the level of eels in our waters have dropped dramatically, and they're now at somewhere around 10% of what they would have been pre-1983," Dr Derek Evans, a senior fisheries scientist from the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) said.

"So we've seen a 90% drop in the number of eels in our rivers and lakes."

Eels in the sleep chamber where they are sedated with clove oil

This year, he and the team at AFBI, who carry out research for the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (Daera), have seen a "noted increase" in the number of glass eels and elvers at all three monitored index sites in Northern Ireland - Lough Neagh, Lough Erne and Strangford Lough.

Across Europe, eels are managed under the terms of regional Eel Management Plans.

As the UK's only commercial eel enterprise, Lough Neagh fishery's plan requires that 200 tonnes of silver eels escape back to sea annually.

But this conservation target has been missed for the past three years, triggering a review of the Neagh Bann eel management plan to address this.

In their life cycle, eels travel from the Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic Ocean as young glass eels or elvers to spend years maturing in European freshwater lakes before returning to areas across the Atlantic to breed.

The trap and transport scheme on Lower Lough Erne has kept some former eel fishermen on the water after the local fishery closed in 2010, when management plans and the associated conservation limits were introduced to protect the species.

Because of the danger posed by the hydropower stations within the Erne system, eels are caught and transported by road to the sea for release.

"We still know so very, very little about what happens in their ocean migration," Dr Evans said.

"And we've still yet to see breeding at the Sargasso Sea."

The sedated eels are put in an aerated chamber before being returned to the water ahead of transport to the sea

Among the assessment catch are long, mature females, aged about 18.

The eels are sedated using clove oil so that Dr Evans and his PhD student group can easily measure them.

"We now know that eels above 70cm in length are carrying in and around one million eggs, so that straightaway is a million-egg female going straight to sea," said Dr Evans.

But he noted the population needed more to help it recover.

"The current advice from the International Council of the Exploration of the Sea says that, in regard to fishing opportunities, there is actually no fishing opportunity for eel.

"And their advice for the entire stock is that when it comes to eel, there should be zero catch of all life stages in order that more silver eels are made available and can make the swim to sea, to increase the amount of spawners available at the Sargasso."

A number of PhDs are funded by Daera, with this year's intake focusing on nature-based solutions in Lough Neagh.

Among them is one student completing his work on pike in the lake.

Craig McCoubrey has asked the fishing fleet to complete questionnaires to help scientifically document the distribution of the predatory fish.

Another student, Niamh Heatley, will start her research this year into how to safeguard eels and support the future of inland fisheries.

Dr Evans and PhD student Niamh Heatley assessing eels

The Lough Neagh fishery is Europe's largest commercial wild eel fishery.

It is worth several million to the local economy and is responsible for more than 15% of Europe's wild eel catch.

But no brown eels will be caught in 2025, after quality issues were reported.

AFBI scientists usually check hundreds of samples from the fishery's catch, but due to the cancellation of the season they were offered just 20.

Dr Evans was among the team that examined them.

"We found that fat content would be similar to what we would have found previously; stomach contents, similar as well, and nothing else was unusual, taking into consideration we had only seen 20 eels, as opposed to 400," he said.

Lough Neagh, like many other freshwater bodies including Lough Erne, is once again experiencing blue-green algal blooms.

But there is not yet any scientific connection between the algae and any problems with eels or fish.

Dr Evans has not been called to any fish deaths or fish kills in three years of algal blooms.

"And I've not had or seen any records of fish dead or dying around Lough Neagh at this stage," he added.

- Published12 August